Image Source: Fox Broadcasting Company

I watch a lot of cooking competition shows. I started with Hell’s Kitchen, then moved on to MasterChef. And most recently, I’ve started watching CNBC’s Restaurant Startup. In the latter two, I have seen the weekly antics of a man named Joe Bastianich, a highly successful restaurateur whose conduct makes Gordon Ramsay’s tantrums look harmless.

Watching Joe lately has got me thinking about a certain kind of teacher.

Here’s the Bastianich method: While taking in a mouthful of the contestant’s food, he locks eyes with them—you can almost hear him thinking, “Give them the signature look, Joe.” If he doesn’t like the contestant’s food, he will berate them for it, calling it disgusting, telling contestants they should be ashamed. But that’s just basic, run-of-the-mill Simon Cowell fare; Bastianich goes a step further by getting physical.

I don’t mean that he physically hurts the contestants—he does stuff to their food, to the dishes they just spent the last hour carefully putting together, and by doing so he takes things to a whole new level of disrespect: He’ll pick up a forkful of risotto, hold it high in the air and let it dribble and spatter all over the plate like so much cow dung. He’ll smash a dessert to pieces, until it looks like roadkill. He’ll grab an entree and hurl it straight into the trash, smashing the plate in the process, just to make his point.

But it was this week’s Restaurant Startup that really did it for me.

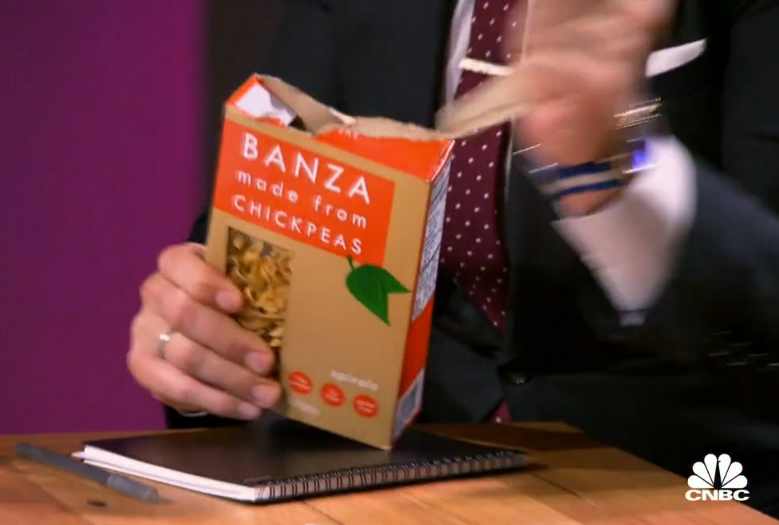

In a meeting with two pasta entrepreneurs, a pair whose company he was just about to invest seventy-five thousand dollars in, Bastianich picked up a box of their pasta…

Image Source: CNBC

Image Source: CNBC

tore it open…

Image Source: CNBC

Image Source: CNBC

then, saying there was “no love in this box,” dumped the entire box of pasta on the table in front of them:

Image Source: CNBC

Image Source: CNBC

Oh Joe. You are such a badass.

It makes for good TV, yes, and I’m sure his producers love it, but to me, it doesn’t look badass at all. It looks weak and cruel. Bastianich is in a position of power, he has money and success, and he abuses it by doing things he can only get away with because of that power. These two guys hadn’t done anything to deserve that; they were excited about their product and needed guidance about the best way to launch it. And in response, because he’s Joe Bastianich and that’s just how he rolls, he pulled a stunt like that.

Just gross.

So here’s my question for everyone who teaches, everyone who coaches, everyone who stands before another person in the name of mentoring or guiding or instructing them in any way: Are you a Bastianich? Do you ever behave in ways that are more about you than about your students? Do you overdo it, put on a big show, humiliate students for the sake of making a name for yourself? Because it builds your rep and makes students fear you? Because, in a sense, it makes for good TV?

Have you ever…

called a student’s question stupid?

read a student’s paper out loud to a class to illustrate a mistake (anonymously or not), and maybe gone too far in making fun of it?

cracked a joke about a student’s appearance?

revealed some aspect of a student’s personal life for the sake of humor?

torn a student’s paper or thrown it into the trash in front of them or other students?

thrown chalk or a marker or anything else across the room to get students’ attention?

assigned a punishment that would publicly embarrass a student, like wearing something silly or doing something embarrassing in a public place?

If this list sounds nothing like you, that’s a good thing. It means you hold your students’ hearts in high regard and would never do anything to hurt them. It also means you conduct yourself like a fricking grown-up. But many others might recognize themselves here, somewhere. Some of these behaviors are harsher than others, but all of them have one thing in common: They are motivated by our desire to communicate something about ourselves, to build our own reputation—a reputation for being funny, for being smart, for being “real,” for being someone not to be messed with.

Does humiliation work? Sometimes. It gets your point across. It stops undesirable behavior, at least in the short term. It most definitely teaches a certain type of lesson. And if you’re trying to prepare your students for an even meaner world, well, you’re no doubt accomplishing that.

But it doesn’t produce meaningful learning. In fact, it changes the subject altogether: When you humiliate someone, their focus moves away from the matter at hand. Instead of thinking about the long-term repercussions of not doing homework, about why they should not socialize at certain times, or even about why using raw flour in a sauce is a no-no, that student is now focused on how much they can’t stand you.

Now sometimes you get a student who you think deserves to be taken down a couple of pegs, to be put in their place, and public humiliation might really teach them a lesson. But I believe it is only a skilled few who can accomplish this with enough finesse that they actually help that student become a better person. And isn’t that what our goal should be, ultimately? If we are true masters of our craft, shouldn’t we be able to effectively shut down a disruptive student and maintain our own dignity? Shouldn’t we model the behavior we want to see?

I’m thinking yes. I’m thinking I don’t want that much adrenaline in my classroom. I don’t want the students with good intentions to be afraid of making mistakes because it means risking public ridicule, and I don’t want the rougher students experiencing yet another crappy role model, and contemplating ways they can beat me at my own game. I have had my Bastianich moments, but I’m pretty sure they came at a cost, whether I knew it or not.

So the next time you’re about to make that big gesture, throw that marker or shut a student up with one of your signature put-downs, ask yourself whether you’re doing it for the student or for yourself. Go into it knowing what you’re doing. Because sometimes, a pile of pasta is more than just a pile of pasta. ♦

If you found this article worth your time, I’d love to have you come back for more. Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more effective and joyful. To thank you, I’ll send you a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half. I look forward to getting to know you better!

While I agree with your discussion of humiliations that teachers might inflict on students and the affect it could have on them, I question using Joe B and Restaurant Startup as the example. Joe B is NOT a teacher. His role in this show is to hand over money to help a good business plan succeed. As a businessman, he wants to make money on the deal. Eventually.

These two kids wanted money, but truly hadn’t researched their product enough to know its strengths and weaknesses. Instead of putting effort into understanding and perfecting the chickpea pasta [does it hold up in sauce well? does thicker work better than thinner? Do any sauces completely ruin it? make it sing?]. Some of these points actually came out in the tasting that they held with local food marketers.

And they questioned the value that Joe B – a member of one of today’s most famous and reputable Italian restaurant families – could possibly bring to their product. The pasta boys actually questioned whether Joe B truly understood how people ate! Frankly, IMO, these boys made this product for themselves and their friends, not for busy families who have an hour to gather the kids, sports equipment, eat, and do some homework. They have more product work to do, and that was the point that Joe B made REPEATEDLY during the show. Pouring out the contents of the box was, I believe, his last attempt to get their attention.

So, all in all, two MBA marketing whiz kids failed to impress with their product, and failed to understand that it needed improvement, yet Joe B was willing to work with them if they gave him a decision making role on the board. I don’t think they agreed to that, did they?

Frankly, I’d be interested in this. But at 4.00 a box, it’ll have to cook perfectly, stay at the right texture for awhile, and be absolutely delicious!

Hi. Okay, in the Restaurant Startup context, you have a point — Joe is not really serving in any kind of mentoring capacity. But I have been watching him on Master Chef for years, and he pulls the same crap on that show as well. It could be argued that he is a judge on that show, and not a mentor, but the show does ultimately constitute a learning environment much of the time. And shockingly, Gordon Ramsay usually does a nice job of supporting and mentoring the contestants on that show — he gives them guidance and support, and pep talks when they really start to lose it. Most of the time, Bastianich is all about himself, and he seems to relish humiliating the contestants. The pasta move on Restaurant Startup was, for me, just one more example of that kind of behavior.

Some of the details you’re referring to in the RS episode I hadn’t paid close attention to — and you’re probably right, he might have tried to make the same point over and over again without getting through to them, so maybe he felt that stunt was called for. I think it was childish and mean, and he could have made the same point with a lot more class and still gotten his message across. Probably better, actually, since there wouldn’t be the emotional residue of a tantrum to slough off.

So the connection to teachers is this: There are most definitely teachers who pull these same kind of stunts, who do dramatic and mean things that kids never forget, but not in a good way. Those people would probably admire a guy like Joe Bastianich. And I think that’s a shame.

(I thought they did take him up on his offer. I kind of remember being surprised that he even made the offer — it made the pasta dumping that much more pointless.)

oops – need an edit button.nstead of putting effort into understanding and perfecting the chickpea pasta [does it hold up in sauce well? does thicker work better than thinner? Do any sauces completely ruin it? make it sing?], THESE KIDS DEVELOPED THEIR MARKETING AND REVENUE PLANS.

As a university educator, I enjoy your blog. Just as an aside, try watching Great British Bake-off. A mentoring approach can be just as enjoyable to watch.

Will do — thanks for the tip!

Wait, you haven’t seen Bake-off? It Is literally the most amazing, pleasant competition show ever and it kind of ruined me for all other competition shows. There are some great examples of good feedback, too, though I like to watch it as a model for how to receive feedback!

Thanks for sharing! I’ll be sure Jenn sees this and now I’ll have to check this out too!

I love this post because it can be applied to so much! Not only for the student-teacher relationship, but the subgroup of the mentor-mentored relationship. As someone who has been on the mentored/student side of things I can tell you that the use of humiliation is still alive and well, (in both subtle and Bastianich ways), especially in groups where there is a hierarchy. Thankfully it’s not something I ever personally experienced in the classroom, but it is a very interesting part of group dynamics. Fantastic post!!

Made me cry. Thanks for reminding me the good will always prevail. If you know what I mean. 🙂

Fantastic post! I’m a 2nd year ELA teacher in need of help. Your post really warms my heart. I totally agree. I also like the analogy!

Thank you, Davina. I feel very strongly about this issue, so it means a lot to hear that it resonated with someone else.

You address a difficult scenario–the moment a teacher humiliates an adolescent or teenager. I say “difficult” because it is most likely handled behind closed doors if at all. I haven’t been in situations where teachers discuss the possibility. Intentional or not, moment of weakness or not, one incidence can cross the line into abuse. You put yourself out there with this post. Much respect.

I agree totally with this practice; I used to throw out my remarks to what I thought were deserved students. The reason? To be thought of as funny, or to make the class more entertaining.

Last Spring I picked up some of the most valuable tip from the program “Orange is the New Black”. While one veteran prison guard was training a newbie, he stated, ” if it makes you feel good, don’t say it”. A revelation went through my mind.

This past school year i refrained, kept my comments to myself and experienced one of my best (20+) years of teaching.

I’ve done the thing where kids are talking to their friend while I’m explaining (I do dance in public schools) then I turn and say “you were talking, so I’m not sure you got that” and they will say “yes I did.” So I’ll tell them to prove it. At that point they either acknowledge they weren’t listening or they try to do it and it’s totally wrong and everyone sees that. Is this somehow a bad thing? I would consider it using public embarrassment to my advantage but I don’t see it fitting in with the descriptions you’ve written here. To me that is a logical consequence of their choice…

And of course this type of interaction only happens after we’ve gone over expectations for the class and why it is helpful and more fun for everybody if you listen respectfully when I’m talking etc. etc.

Would you publicly embarrass a friend, relative or your child?

Please don’t do that to a student. Talk to them privately about what it was like for you to teach and the didn’t listen. Let them know they matter, please…be human with them. You may be surprised.

Humiliating others with loud, crass gestures, mocking, denigrating, bullying — all of these have become the currency of reality TV. We have just witnessed the consequences of how it has enabled a culture which accepts meanness over kindness and understanding.

The example works. I teach university students and have heard of this kind of treatment of students. I have also coached middle school football for the last 18 years, and the “drill sergeant” mentality is still present. I see coaches who still believe you have to “break down” a player to build them up. The only problem is you can never fully repair what you broke. I have been told I couldn’t be an effective coach because i refuse to yell, scream and belittle players. The truth is, I have formed long term mentoring relationships with players because I respect them as people. The same applies in the classroom. I tell my classes one of my goals is to create community in the classroom, and you cannot create community unless every student is seen as a human being; unique, unrepeatable, deserving of dignity and respect. Humiliation is never good pedagogy.

Students will remember you for how you made them feel. Thank you for sharing this post!

“Be kind whenever possible. It is always possible.” – Dalai Lama

I did not read the whole post but just the half I read represent so much the society that we are creating and then we complain for it. We think that being disrespectful and cruel is funny and even, for some, good TV. Then we think that they children are disrespectful or defiant, well what can you spect if we clap and laugh and watch shows where the example is so poor. Sad but true, I think is a great example for many things that are happening in these days. I hope we can give a better example to our children because they are the future grown ups. I really enjoy your podcast and posts, congratulations for your hard work!!

Thanks so much, Eduardo!

This sort of behavior is a form of bullying we don’t want students to engage in. When a teachers humiliate student there is an audience of other students watching. Some may be horrified and intimidated, but others may embrace the idea that this is a useful tool in life and become bullies themselves or the followers of bullies. It also divides a class in insidious way: There will be some students who cower in fear when the teacher turns his/her attention on them; other will shun the humiliated student, not wanting to get caught up by association with the victim; some may even align themselves with the teacher, believing that the student deserved the treatment. Some students watching these tactics will become teachers themselves and hopefully reject using them in their own classroom. Unfortunately, others will decide that they are useful tools and carry their corrosive effects forward to another generation of students.

This is such an important idea that is linked with the value I place on respect for the student.

It reminded me of a day I totally lost it with an (adult) student. “I knew I should apologize, and I knew I could get away with not apologizing. No one would call ME on bad anger management.”

https://katenonesuch.com/2012/08/08/im-sorry/

I just found your blog and am enjoying exploring it immensely.

I’m of the mind that avoiding shaming strategies is much harder than we might think. For example, “It also means you conduct yourself like a fricking grown-up,” is itself a use of shaming, with the implication that it’s bad for adults to act like children (and by extension you’re a bad adult/teacher if you do)—though this sidesteps a question of whether we should assume children use shame by default. Your sentence immediately prior to this one, “It means you hold your students’ hearts in high regard and would never do anything to hurt them,” also risks inviting shame by excluding those who *do* identify with (at least part of) the list. Do they not hold their students hearts in high regard? Would they willing do something that they know could harm students?

I generally appreciate your work (I particularly like How to Stop Yelling at Your Students), and I would attribute to you a positive regard and intention for your students—you don’t want to harm them. But we can have that intention and still commit harm—and still use shame. Because hurt people hurt people, and who isn’t a person with some hurts? I identify both with items on this list and with items that should be, the most pressing of which I did in a context with pervasive acceptance of teachers’ controlling behaviors. I am accountable, and so is that system.

Now I believe that shame is *categorically* an inappropriate motivational strategy—even for those who might consider themselves able to use it with “finesse” because (and this is a large part of what I think is missing from this post) the reason a thing is done is often as important as simply that it is done. Beyond the distraction of a student focusing on how much, “they can’t stand you,” is the possible distraction of considering, “How can I prevent my teacher from humiliating me in the future?” The motivation to avoid is not the motivation to mastery.

Jakob,

Thanks for adding your thoughts to this post. I think you bring up something important that we should consider–our reaction and the why behind that reaction. I think that all behavior is a form of communication. As educators, I think that it is important for us to respond to situations with our students and in our classrooms by asking ourselves, what is this learner attempting to communicate to me? What about this environment and/or situation is not meeting this learner’s needs at this moment? Furthermore, thinking about the intent vs. the impact of how we respond as the educators in these situations might have a long-lasting impact on the relationships that we have with students as well as the culture and climate of that classroom environment.

I generally have it together but have been guilty of the pen toss a few times before. Really enjoyed this read and the reminder that it’s not about us but the issue at hand.

What are some better ways of addressing talking during a test?

It’s okay to ask a student or students to not talk during a test. “Just a reminder, there shouldn’t be any talking right now.” You can also use proximity — stand near the students who are talking or are prone to talking. Rearrange student seating during a testing situation, putting those prone to talking nearer to you or a little further away from others. These are things I have used with success. Maybe they will be helpful to you. It’s frustrating, for sure, because it seems like such common sense not to talk during testing.

Carol,

I think I’d first identify why students are talking during a test. There could be multiple reasons, they may need clarification of directions, it might be that they are being social, or it could be a host of other reasons. I immediately thought of Jenn’s post: When Students Won’t Stop Talking as a possible solution. Also, I recently had a teacher share a testing strategy that I found to be unique–the teacher builds in a “collaborative” turn & talk time during a test. So, students begin the test and part of the way through the assessment, students are given a time to turn & talk about the assessment. Not in a way that students give each other answers, but that the students talk specifically about the questions–which they feel prepared for, which is the most difficult, etc. they then resume the assessment. Also, note that this teacher using multiple assessments and ways to determine student mastery, so this assessment isn’t the only time that students are able to demonstrate what they know, understand, and are able to do.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

As a teacher who has worked with thousands of at-risk youth, I am often reminded of this phrase. Many say, “Treat others as you would like to be treated.” My conversations with students are always, “Hey, can I talk to you for a second? Hey, you know I have an idea, how about we do what we are supposed to do? Hey, I want you all to have a great life.” I ask a lot of questions and avoid humiliation. I know when I was humiliated in school — in the hallway. I was 18. I cried. “Charvet, you are the only one in the class who failed. You did the assignment completely wrong.” It still hurts. Thanks man for such fond memories. I use it as a teaching tool. Just recently, I was called into the admin office for some unfounded reason. I told him, “You know, you might remind me of some positive things I do.” Yeah, well no comment. I guess I know what he thinks about me. I read the works of John Wooden and other great coaches. All the great ones have stated, “Be kind with your words. These kids are a captive audience. They are hinged on your every word.” I am 60-years-old. I remember the teacher who said, “He is an honest young man.” And, I remember making the 100th point in the basketball game — coach said, “If you would have missed the shot, I would have been really mad.” So, yeah, stuff like that is like Velcro, it sticks around for a long time. Managing personalities is difficult, but perhaps count to 10, take a chill pill, or just invite the student to chat at a break. When we all take a few extra moments in the hall, at lunch, after school or at a “teachable moment,” the magic happens. Just sayin’.

Well written and great points made. But I think it’s worth mentioning even more subtle forms of humiliation, things like when a kid is talking during class when they’re not supposed to, for instance, and the teacher goes off on a rant. “Why do you keep talking during the test? Isn’t this something you should know by now, that you don’t talk during tests? How many years have you been in school and you still haven’t figured this out?” Behaviors like that are not on the list you created but they are designed to humiliate the student nonetheless, and they come a lot more naturally when a teacher is just frustrated and at the end of his/her rope. I think that it takes a really strong, self-aware, and empathetic teacher to recognize when he or she has crossed a line and then apologize to the student. I know I certainly haven’t been perfect in the 30 years I’ve been in education, and whenI recognize that my actions belittled a student, I apologize. It’s not easy, but it’s appropriate, I think. Anyway, like I said, great post!