A “Day in the Life” Memoir by Jay Malone

In 2009, I was invited to take over the directorship at a language school in Kazakhstan called Bisodev Training Academy. The founders of the school, Nursultan and Abdullah, were two local businessmen who wanted to take advantage of the explosion of economic activity centered around the local oil industry.

When I arrived, one of my first questions was about the name Bisodev, which seemed both inexplicable and a fairly poor piece of marketing. Apparently it was formed from the last names of both of the founders, plus the common Russian suffix –dev, which apparently meant that this was a partnership, as it was explained to me. I encouraged Nursultan and Abdullah to change the name from the start, because I thought it obscured the nature of what we did, but they held firm, and I became the Director of Education at the Bisodev Training Academy in December of 2009.

When I arrived, one of my first questions was about the name Bisodev, which seemed both inexplicable and a fairly poor piece of marketing. Apparently it was formed from the last names of both of the founders, plus the common Russian suffix –dev, which apparently meant that this was a partnership, as it was explained to me. I encouraged Nursultan and Abdullah to change the name from the start, because I thought it obscured the nature of what we did, but they held firm, and I became the Director of Education at the Bisodev Training Academy in December of 2009.

After a trying few months, I found a comfortable routine, and our first two months of classes, which we referred to as semesters, passed nearly without a hitch. As the second semester approached, I had more than a few issues to deal with. We’d been successful in attracting a variety of clients, but we were having problems when they actually made it into the classroom, something I needed to fix as soon as possible.

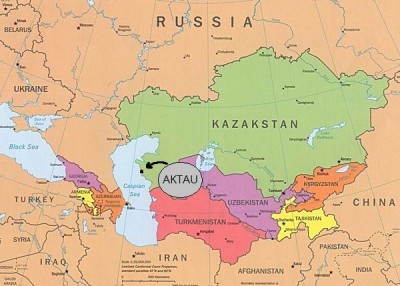

On the Monday before the start of the new semester, I walked out of my apartment to hail a cab. Aktau is a planned city, built in the 1960s by the Soviets to mine uranium, and consists of a square arrangement of bland, uniform apartment blocks, marked on one side by the Caspian Sea, and on the other three by the seemingly boundless stretches of the Kazakh steppe, which covers much of the massive country from the sea all the way north to Siberia and west to the Tien Shen mountain range in the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains. The uranium was long gone by 2009, but as a result of the discoveries of massive oil fields off the Kazakh coast, the area was still abuzz with economic activity.

Thanks to the layout of the city, I could hail a taxi from anywhere and only pay 250 Kazakh Tenge, a little less than a dollar for a ride. And as with most former Soviet states, every car is a potential taxi, meaning I rarely had to wait more than a minute or two for a ride. Once I got to the main road, I put my hand up, and a pre-independence vintage Lada pulled over to pick me up. These tiny little Carbon Dioxide factories once monopolized the roads in cities like Aktau, but despite their interchangeable parts and simple design, natural wear and tear and the increasing affluence of the city had reduced their number significantly by the time I arrived. It’s hard to imagine the streets there without them, but they’ll surely be a forgotten relic of Soviet enterprise within a generation.

It was only a five minute drive into the heart of the city, which consisted of a stretch of newly constructed, gaudy glass-fronted “Business Centers” accented by the odd, vaguely Western restaurant or bar, with names like “Guns and Roses.” Across the street from my office, there was even an Irish Pub called “The Shamrock.” There wasn’t much Irish about it, but it did have Guinness, a relief from the largely flavorless “Baltika” beer that’s on tap at most bars in the former Soviet satellites.

Student Dissatisfaction

My first task when I walked in was to deal with a serious problem that had been festering since the beginning of the semester, but which I’d only become aware of recently: Our teachers weren’t teaching how they’d been instructed to teach, and the students weren’t happy.

Bisodev’s main focus was on in-company trainings with an eye to preparing workers and executives to interact with their international colleagues. But the majority of our students actually signed up personally for our small group lessons, which took place in our three classrooms in the Grand Victory hotel overlooking the Caspian Sea. In the first semester, we had approximately 150 students, all of whom were placed into seven separate categories: Advanced, Upper Intermediate, Intermediate, Lower Intermediate, Elementary, Beginner, and Bless. “Bless” was a term that I wasn’t familiar with before I arrived in Kazakhstan, but it’s one that is fairly common among English as a Second Language schools in Ukraine, which is where our program originated. This was the only level that was taught exclusively by a local, Russian-speaking teacher; the other six groups were all taught by two teachers in tandem: one day per week with a native English speaker, and one day per week with a local Russian teacher. The idea was to give them one class worth of intensive grammar using more traditional rote-based techniques similar to what they would have experienced in school, followed by a more progressive lesson, which used no text and entirely focused on improving speaking and listening comprehension.

The author teaches a class.

In the Bless classes, the students had no experience whatsoever, so we recognized the need to take a different approach. Many of the students in Bless had limited educations, some having as little as five years of schooling, and thus they had a natural discomfort with being thrust directly into a dynamic classroom environment in which they needed to speak and listen actively. Instead of overwhelming the students at this level, we decided to ease them into the process by having local teachers teach them initially using more traditional methods while gradually introducing some of the techniques into the class that students would see in higher levels.

In general, the first semester was overwhelmingly successful, with approximately 85 percent positive student feedback with retention rates of around 75 percent. This was essential for our program to work, and for a young school, we had to be happy with those results. If we retained students at a 75 percent clip, then we wouldn’t need to recruit new students for the classes at the higher levels. Fortunately, most of the students who hadn’t renewed for the new semester were at the Bless or Beginner levels, which meant we just needed to continue recruiting at those levels to feed into the program.

And this is where my problem came in. We relied on the local teachers most at the Beginner and Bless levels, and that’s where I’d been getting the highest rates of complaints and cancellations.

The problem with attracting talent to Aktau was one I recognized as soon as I took over the school, but I assumed the challenge would be in recruiting the Anglophone teachers. At the end of the first semester, I’d been able to bring in Andy, a teacher I knew from a previous job in Slovakia who had been teaching in Ukraine, and I had a new teacher due to arrive from Boston in around four weeks. Between the three of us, we could easily expand and take on new corporate contracts. The problem, though, was that that assumed we would have sufficient support from a larger team of local teachers. And now, I was starting to question my current team of local teachers.

I couldn’t help but feel disappointed; the local teachers were the ones I thought were the most rock-solid among us. I had concerns about Andy, because I didn’t know much about his background, and I wasn’t sure if I could teach the classes either, but our local team came credentialed, experienced, and seemingly overqualified. One was a 30-year veteran English teacher with practically flawless pronunciation and the Soviet equivalent of a doctorate; another had two Masters degrees and had worked for several companies in the region as a translator.

“We Are Learning English Right Now”

In order to get a sense of what was going wrong, I had decided the week prior to sit in on a class being taught by our most experienced teacher, Olga. When I started at Bisodev, I’d instructed her about the program, her role in explaining grammar and preparing students for their sessions with me and Andy, and had left convinced that she not only understood, but was enthusiastic about being a part of our program. Because she was an experienced teacher, I wasn’t particularly worried about her ability to explain the grammar, and I basically allowed her to teach the entire semester without any oversight. I had enough to do without looking over her shoulder every week. This, as it turned out, was a big mistake.

It became rapidly apparent during the class that Olga neither understood nor had much enthusiasm for what we were doing. Instead of explaining the grammar for the upcoming lesson, which was on the present continuous, she read the exercises from the book and instructed the students in the classroom to repeat them.

The author, Jay Malone, with three of his students.

“We are learning English right now,” she read.

“We are learning English right now,” the class repeated in unison.

“We learn English every week,” she read.

“We learn English every week,” they repeated.

“What are you learning?” she read.

“What are you learning?” they repeated.

The students were mostly attentive, but judging by the epidemic of yawning that broke out 20 minutes into the 2-hour class, I could tell they weren’t very engaged. I tried to imagine how I would have felt had I been in the class, and I could feel my annoyance rising at Olga’s seeming refusal to follow what I thought were very clear instructions. Russian has no continuous tense, and Russophones generally have a great deal of trouble using English tenses correctly, so I wanted her to spend the class preparing the students for the practical lesson they would have with either me or Andy. This was not only because I thought it was valuable, but also because students expected grammar, having been taught throughout their lives that grammar lessons were an essential part of language learning.

This was even more problematic because much of the lesson was designed to elicit responses, and there was no value in the students merely repeating the questions. I’d given Olga a copy of the book that Andy and I used in class so she could prepare the grammar lessons to fit with what we would be practicing; instead of doing that, she was teaching them everything we did in class by rote, essentially sapping our lessons of both their novelty and much of their value. Merely regurgitating sentences on command doesn’t do much for understanding, and the difficulty some of my Elementary and Lower Intermediate students were having with more complex grammatical structures suddenly made a lot more sense.

After seeing this and speaking to some of my students, I found out that the techniques Olga was using were the standard method used in most Kazakhstani schools, but it wasn’t how we did things, and it was completely unacceptable in the context of our classes. The students needed to learn the grammar, and I was disappointed to find out that these classes with Olga were essentially a wash for them.

I soon found out that all of our local teachers, despite our initial training on the methodology, were doing the exact same thing.

I’d considered having a “Come to Jesus” moment with the staff, getting them all together in the office and trying to get on the same page. But I realized that the problem was deeper, and it couldn’t be solved so easily. I would have to fire Olga and bring in some new blood. Previously, hiring had been largely done based on qualifications and experience, but I recognized now that I’d have much better luck by personalizing my approach and focusing much more on training. With Olga and the other teachers, I’d spent an evening going over the program and explaining what would be expected of them, but we hadn’t actually done any training. The Russophone teachers weren’t expected to explain grammatical concepts in English, like Andy and I had to do in the upper level classes, so I assumed that an overview of the program would be enough.

But this didn’t take into account the dismal state of pedagogical practices in Kazakhstan in 2009. Attempts were made post-independence to reform the rotten and corrupt university system that the country inherited from the Soviet Union and to improve the quality of instruction while reducing the rampant culture of academic dishonesty that had largely discredited higher education in most of Central Asia. This is so bad in the region that the government of Kazakhstan’s post-Soviet cousin, Tajikistan, won’t hire applicants with Tajik university degrees issued since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and most Kazakh universities struggle with the same baggage endemic to countries with low professorial salaries and poor standards for secondary education.

I’d assumed that a teacher with 30 years of experience and a dresser full of degrees would be well-suited for classes like the ones we were offering. But I was wrong. Instead, I decided that we needed to bring in some newer teachers, ones that hadn’t been corrupted by old methods and who might be more capable of wrapping their heads around what we were trying to accomplish and how we needed to go about doing it.

The Search for Better Teachers

So instead of starting my day with the normal administrative work that most Mondays would have consisted of, I had asked my assistant, Aigul, to set up a series of interviews for new teachers. The first candidate, Martin, showed up promptly, which was a positive sign, considering the contentious relationship most Kazakhstanis that I knew had with keeping dates and appointments. Sizing him up during our initial handshake, I couldn’t help but lean on my Western prejudices, which told me immediately that I wasn’t going to hire him. He was only slightly overweight, but his two-sizes-too-small shirt did little to obscure it. I could also see several stains on his pants, which appeared to have been recently laundered to little effect.

I was therefore a bit skeptical at first, but as the interview went on, Martin turned out to be a fantastic candidate. His English was flawless, better than Aigul’s, in fact, and he even spoke some German, a major plus since I was interested in offering a beginner German course in the future.

My first question regarded his background. I wasn’t as interested in the actual details of his experience as his ability to effectively present them, which would give me insight into his classroom presentation. He had a master’s degree, something I’d come to expect from all candidates, since it was fairly easy to come by one in Kazakhstan, but he did a fantastic job of laying out his professional experience, which, while not that extensive, did include time spent at what the locals referred to with reverence as an “international company,” a major source of pride and a good sign for any job candidate.

My follow-up questions all involved scenarios that he might find himself in while teaching. These included a situation where he wasn’t sure about the answer to a question about grammar, a realistic scenario that I’d found myself in the previous Friday. He said that he would tell the student that he wasn’t sure, but that he would find out and tell him next week, which is exactly what I did and what I wanted the teachers to be willing to do. Kazakhstani teachers are always referred to by their patronymics, for instance Vladimir Ivanovich, which in my experience was often a placeholder for the work that teachers needed to do in our field to establish their legitimacy. Instead of proving themselves, they maintained a dignified distance from their students and used this to elevate themselves above any doubts. I always asked students to call me by my first name, even though my patronymic, Jay Mikhailovich does sound pretty good, because I wanted to prove myself in the classroom. And I could tell from Martin’s answer that he was of the same mind.

After the interview ended, I was excited, because I thought that I’d found a fellow pedagogical traveler who would be a great addition to our team. Outside of sartorial reservations, he seemed perfect, so I told him that as long as he was sure to dress professionally — which for us meant a clean Oxford shirt and slacks — then he had the job. I felt like I had my guy to replace Olga on the team, and I told Aigul to follow up with him in the afternoon to confirm and set up an appointment so we could go over the program and I could explain in detail what I would expect from him.

Four hours of interviewing later, I took a break to assess the day. During my last interview, Martin had followed up with Aigul. I wasn’t surprised by this, because I knew what a great opportunity this was for him, and I assumed that he wanted to express his appreciation for the opportunity to interview for the position. Instead, it turned out that he’d actually called to complain about me. Taken aback, I asked why, and Aigul said that he’d been insulted by my fashion advice, had yelled at Aigul for what she said felt like an hour, and then emphatically turned down the job.

In the end, though I was disappointed by Martin’s response, we were able to fill out our new team. Two of the interviewees we’d scheduled didn’t show up, but of the three besides Martin who did, two seemed promising.

Troubleshooting

Having finished the interviews for the day, I walked across the road to get some lunch. As I walked back to the office with a shashlik in my hand, I took a minute to turn the flatbread in my hand. The yogurt sauce was starting to drip out of the tin foil, which never seemed to be able to contain the wonderful combination of lamb and onion that makes up this regional delicacy. I tried to balance everything by propping the door open with my foot while sliding past it quickly, and it was only when the door slammed shut that I noticed who was sitting at the desk in front of me.

A neighborhood in Aktau.

It wasn’t Aigul, as I’d expected, but rather Valeriya, one of our local teachers. It wasn’t clear why she was there, but I knew it had something to do with the last conversation we’d had, when I told her that she needed to dress more appropriately for class. When I first met her, on her first day of class, she’d practically caused a riot when she walked in wearing thigh-high stilletos, black tights and a top with a neckline that plunged nearly down to her navel.

It was when she started to cry that I realized her visit had nothing to do with fashion. I noticed how dressed down she was; gone were the heels, replaced with a pair of Converse All-Stars. It quickly became apparent why she’d come: she’d spent the last few days trying to figure out how to convince me not to fire her.

“Please Mr. Malone, I promise to be better!” she said. I’d told her before that she should call me Jay, just like everyone else does, but she had always insisted on calling me Mr. Malone.

“It’s not that big of a deal, Valeriya, I just need you to think about it in the future,” I said. It really wasn’t a big problem, in fact it was the same as the situation with Martin, just an afterthought that I was now realizing had cultural overtones in Kazakhstan that I hadn’t even considered. In her mind, she’d committed some grievous error, despite the fact that I had tried hard to get across how minor the problem was. This was a common problem with my local teachers, and it was why I generally preferred to spend time with Andy. There a cultural understanding between the two of us that I’d never have with Valeriya. We said the same words, but didn’t speak the same language.

I spent much of the next hour comforting Valeriya and trying to convince her that I was happy with her performance, if not her presentation. And, in the end, that was what really mattered to me. By 3:30, I had finally calmed her down, and I walked her out, still wondering if I had really gotten through to her.

Andy wasn’t a professional teacher, so I’d decided to make his life easier, and improve the overall experience of the students, by creating a set of lesson plans for each level that we taught. This would also make it easier in the future to bring on new teachers, since we would be able to hire without worrying about experience. For the last few weeks, I’d spent most of the day on these lessons, and I settled in for the next hour creating detailed instructions for each of our classes.

At 5:45, I looked up and realized that I needed to get moving if I was going to make it to my evening class. When I took over, Bisodev essentially consisted of me and Aigul, which meant that I had initially taught all of the classes myself with the support of the local teachers like Olga and Valeriya who I’d hired in the weeks before classes started. This was part of the reason why I’d neglected the local teachers more than I should have; I was simply too busy managing, marketing, and teaching at the school. After a month I brought Andy on, which freed up half my schedule and allowed me to focus more on what I’d been hired to do, which was to administer and promote the school. Until our third teacher arrived, though, I still needed to shoulder a large number of classes. On Monday, I only had one class, our intermediate class, one of the two levels Andy and I taught exclusively. That meant that I would be teaching grammar tonight, a prospect I didn’t relish.

When the class ended at 8:00, I walked out and caught a cab, this time a Chinese-make SUV that was much more comfortable than the Lada I’d ridden in earlier. The semester was almost over, and I’d addressed my biggest concern. I hadn’t landed the teacher I wanted to take over for Olga, but I’d found two solid replacements, and I had a message waiting for me on my answering machine from Valeriya that assured me that I didn’t have to worry about her. The next day would be another busy one; I still needed to prepare nearly 100 lesson plans before the start of the next semester. But as I poured myself a glass of wine and settled down with a book, I felt confident that everything was going to work out. ♦

Although we occasionally feature posts about interesting teaching-related stories like this one, our main focus is to help you become a better teacher. Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more powerful and fun. To thank you, I’ll send you a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half. I look forward to getting to know you better!

Thanks for this! It’s a fascinating look and most interesting. I’ve linked to it from our page on Kazakhstan and hopefully our students will also find it as useful as I did.

Hey, thanks for letting me know that! If you’d like to add a link to your page here, go right ahead. Add a description of what you do, because others who visit this article are likely to be interested in your organization as well.

Wow, I am shocked by the cultural insensitivities and US imperialism shown by this teacher. Did this guy spend any time getting to know the people he was serving? I’m left unclear from his writing if this is trying to be a sheepish account of a culturally clueless teacher, or if it’s slamming the backwardsness of Kazakhstan. I’m grateful on his students’ and colleagues’ behalf that he is no longer working at that school and I hope he’s happier now, living in Germany, where people are punctual and their master’s degrees meaningful.