Listen to my interview with Michael Linsin (transcript):

Sponsored by Write About and Peergrade

In my first few years of teaching, student talking was like popcorn.

I gave the class instructions for some kind of work; let’s say journal writing. And for a few seconds, they did it. Things were quiet. Then, like that first kernel of popcorn, one student said she didn’t know what to write, so I walked over to her desk to help her. While we talked, two more raised their hands—two more pops—and said they were stuck, too. I signaled to them that I’d be over in a minute, but in the meantime, someone else was closing his journal, finished already. Another pop. The two who were stuck asked him what he wrote about.

The room needs to stay quiet so we can concentrate, I told them.

Someone else had a question. Another pop. I squatted by her desk, and behind me, a conversation started between two others. Pop pop. Another journal closed while a different hand went up.

Okay people, I said, this time louder. Let’s keep it down. And with rascally smiles, they turned back to their journals to pretend to write some more. At this point, it had turned into a game.

Someone needed to sharpen their pencil. Pop. Someone else decided to race them over to the sharpener. Pop. In a matter of seconds, the whole room had erupted, a huge hysterical bowl of popcorn, exploding all around me, and I couldn’t find my way out.

And then I yelled.

If this sounds anything like you, you’re not alone. I hear it from teachers all the time. One of the things they don’t teach us in our education courses is just how freaking much students talk, and how hard it can be to quiet them down in order to get anything accomplished.

To find solutions to this problem, I went to Michael Linsin, the creator of Smart Classroom Management and my go-to person for all classroom management needs. Last year, he taught us how to set up a clear, simple classroom management plan. Now he’s going to help us understand the causes of excessive talking, what you should be able to realistically expect from students, and how you can fix the problem.

Michael Linsin of Smart Classroom Management

First, two quick caveats.

One: I believe students need to talk. People need to talk. So if you’re shooting for a classroom environment where students sit silently and do rote seat work all day long, where they never have an opportunity to talk to their peers, where they never get out of their seats, and where the work is not engaging, you are going to have problems.

Two: A big part of good classroom management is building good relationships with your students. If you haven’t taken the time to get to know them as individuals, if you mispronounce their names, if you regularly use sarcasm or make them feel stupid for asking questions, then they aren’t going to want to behave well for you. And that’s a different problem.

So this post is based on the assumption that you’re planning engaging lessons and you have a decent relationship with your students. Without those two, these solutions might kind of work, but you’re still probably not going to love your job.

Why It’s Happening

Before you can solve this problem, you have to understand its cause. According to Linsin, excessive talking—talking that occurs during independent work time or direct instruction—happens for two reasons.

Reason 1: They don’t believe you mean it.

Despite the fact that you specifically tell students not to talk, deep down they don’t believe you mean it. “Or they don’t care,” Linsin says.

“At some point,” he explains, “Your authority has faded. If you’re able to teach to a quiet classroom in the beginning of the year and now you’re not able to, or if it happened right off the bat, then somehow at some point, the students’ respect for you and for the process, for the classroom, and your authority has faded.”

So even if they hear you, even if they understand that you want quiet at a certain time, they don’t believe anything negative will happen if they ignore your request. If they come to you with this behavior, it’s likely that it has just been part of their conditioning.

“Because so many teachers struggle with this problem,” Linsin explains, “many after a while kind of throw up their hands and just decide they’re going to talk over students, they’re going to do their best to keep things as quiet as possible during independent work time, so the students come to you (from) classrooms where the teacher asked them to be quiet but doesn’t really follow up on it.”

Reason 2: They don’t understand what “no talking” means.

This one is going to be harder for teachers to believe, but bear with us here: “No talking” may not mean exactly the same thing in different contexts, and if your students are talking more than you want them to, there’s a good chance you’re working with different definitions.

“When they come to your classroom,” Linsin explains, “and they’ve had teacher after teacher say the same thing, yet continue to allow it to happen in the classroom, then students think, Well, he or she just means we need to kind of keep our voices down, or We’re mostly quiet, but if we have important things to say to a neighbor, then we’re allowed to do that. And so they’re confused as to what the definition of ‘quiet’ really is.”

In many cases, Linsin notes, the problem is likely being caused by a combination of both of these reasons. But notice that neither reason is a blanket statement about students being disrespectful. This is why I like Linsin’s approach: He puts control for classroom management in the teacher’s hands, rather than placing blame on the student. That’s not to say that you won’t have disrespectful students, but shifting the blame to them means you have no power over the situation. Blaming the students simply isn’t a useful way to address the problem.

“When students are not doing something that you’ve previously taught them how to do,” Linsin says, “whether it’s talking or entering the classroom, and they don’t do it well, even though the students are responsible for their behavior, when most of the class is not doing what you ask, it’s on you. It’s about you. There’s some disconnect there, there’s something they’re not understanding.”

What You Should Be Able to Expect

Some teachers might wonder whether it’s reasonable to expect students to be quiet at all, especially if they are younger. Linsin says yes without hesitation. “You should absolutely expect, no matter where you’re teaching or what grade level, that the students are able to sit quietly while you’re giving instruction or directions, and they should be able to sit quietly and work during independent work times.”

Should there also be times when talking is permitted? “Absolutely,” Linsin says. “It’s really important to give students an opportunity to express themselves, to get up and move around, to work in groups and pairs and discuss. Classrooms should be vibrant and interesting, exciting places, and so I’m all for getting students up and moving and having fun. Those things just make classroom management stronger, and they free you to ask anything of your students, including silence.”

The Solution

If you came here looking for a few tricks to end excessive talking, the bad news is that you won’t find anything clever or earth-shattering. The good news is that the solution is pretty simple, and it requires no behavior charts, tokens, or Jolly Ranchers.

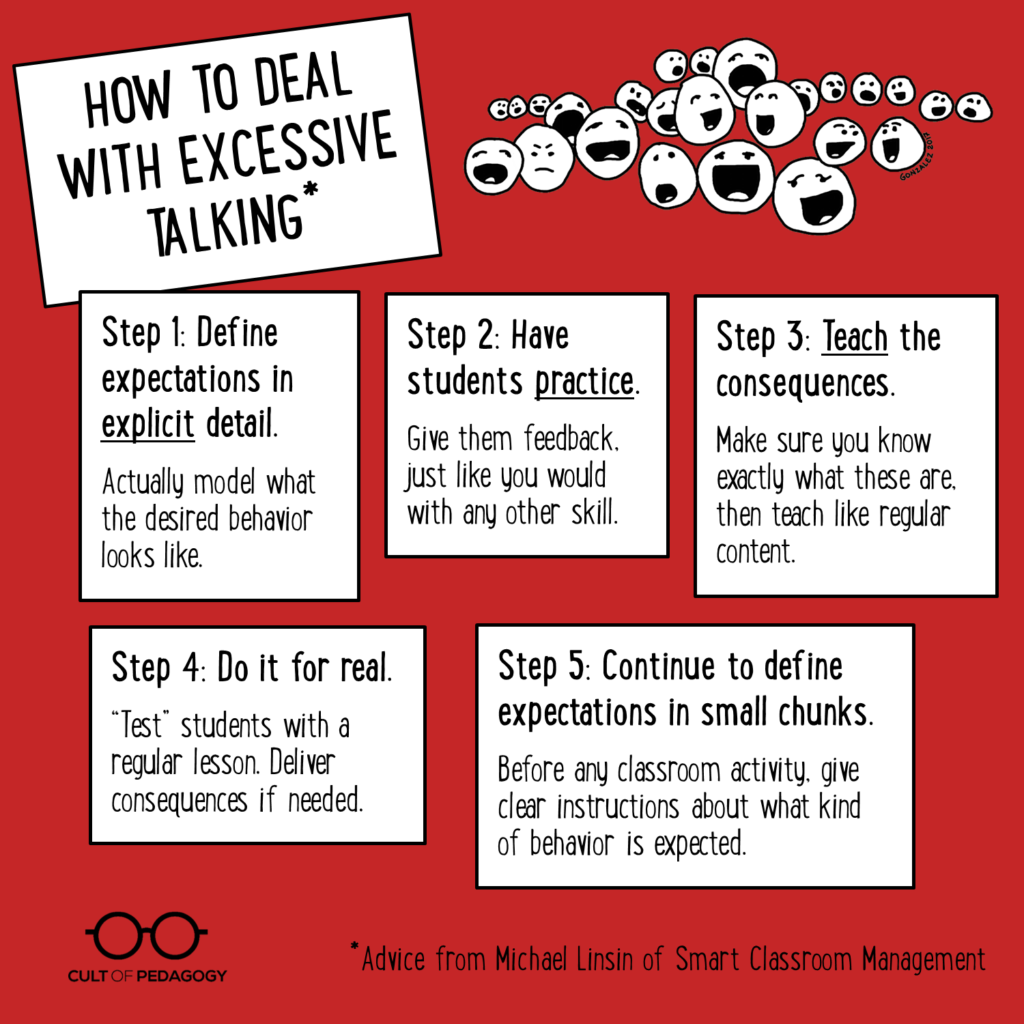

Step 1: Define expectations in explicit detail.

“The fix,” Linsin says, “is to define, in detail, exactly what you want during independent work time and when you’re teaching a directed lesson.”

If you believe you’ve already done this, and it hasn’t worked, the issue is probably lack of detail in your explanation. Linsin says you need to go far deeper than what most teachers probably do.

“So you may bring a desk or a table up in front of your classroom, sit down, and pretend to be a student. You may have other students acting as models also. Show students how you expect them to behave while you’re giving instruction, and then how you expect them to behave when they’re doing independent work.”

“It’s also important to include what not to do,” he adds. “So you’ll model those exact behaviors that you’re seeing, those exact talking behaviors, whether it’s side-talking or standing up and whispering to someone, or whatever your classroom looks like. Even if it’s chaotic, whatever that chaos looks like exactly, you want the students to be able to see themselves in your modeling and what isn’t okay.”

Step 2: Have students practice.

Once you’ve modeled the desired behavior, have students practice it, just like you’d have them practice any skill you’re teaching.

Linsin gives an example of what this might look like. You’d start by saying, “‘I’m going to give you 60 seconds, and I want you to show me what good listening looks like, and no talking. So let’s pretend I’m standing and giving you a lesson. I want to know what that looks like.’ And then you’ll stand and maybe you’ll cross your arms and put your hand under your chin, and you’ll watch them.”

Keep this instruction light, he says. Keep it fun. “You’ll stare at them and you’ll walk around the room, and you’ll watch one of them, and you’ll nod your head and say, ‘Mmhmm, okay, that looks good. Mmhmm. Chin up a little higher!’ It’s okay to have fun with it. None of this is a punishment. It’s just good teaching. Whether you’re teaching how to find a topic sentence or how you want your students to line up before recess, it’s all teaching. So it’s okay to have fun with it. It’s okay for them to laugh at some of the things you say or to see themselves in the behaviors, which they love, by the way, especially if you exaggerate it and have some fun with it.”

The Sign Strategy: Students are often put in an awkward position when a classmate tries to talk to them during these quiet times. They want to follow your guidelines, but they also don’t want to be rude to a classmate. Agree on some kind of physical sign they can give each other at these times. “It can be a scissors or peace sign or whatever’s culturally acceptable wherever you teach. And all they do is just hold the sign up, and the sign means, ‘I’m really sorry, but I have to listen to the lesson,’ or ‘I’m really sorry, but I have to do my work.’ And you can tell them that if they give the sign and that student who sees the sign turns and gets back to work, you will not enforce a consequence, because they’re showing responsible behavior.”

Step 3: Teach the consequences.

“Walk them through the exact steps that would happen if they turn and talk to a neighbor, for example,” Linsin says. “The exact steps a misbehaving student would take from your initial warning to contacting parents or whatever your consequences look like.”

In order to do this, you have to know what your consequences are. Spend some time making sure you’re clear on that. If you need help, read our post on creating a classroom management plan.

Step 4: Do it for real.

Once students have been taught your expectations and have practiced exactly what they look like, it’s time to apply it in a real lesson. “Have a directed lesson ready,” Linsin advises, “to have them prove to you they can do it in practice.”

If you’ve taught the expectations in detail, students should do a good job, but if they don’t, you need to enforce your consequences exactly as you described. “You almost hope during that first wonderful lesson, that one student maybe turns, and so the class can see that you’re holding them accountable.”

If enforcing your consequences is difficult for you—and for many teachers, it will be—read Linsin’s post on why teachers struggle to consistently enforce consequences.

Step 5: Continue to define expectations in small chunks.

This last step is crucial. From this point forward, keep telling students what is expected of them before every switch in classroom activity. When you are about to do group work, let students know that talking within the group is okay. If you then switch to independent work, remind them that absolute quiet will be expected. Briefly describe what that will look like, even spelling out what not to do if that fits the activity.

Taking time to do this might seem unnecessary, but being clear ahead of time will prevent problems. “Anytime you can give a reminder before misbehavior,” Linsin says, “it’s a good thing. Anytime you give a reminder after you see misbehavior, it’s a bad thing. You should be holding students accountable, but be preemptive whenever you can.”

Learn More from Michael Linsin

(Links to this book are Amazon Affiliate links, which means I get a small commission on purchases you make through my links at no additional cost to you.)

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration—in quick, bite-sized packages—all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to my members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Come on in!!

I have the opposite problem with my seniors who I had as juniors they will not talk or discuss when I open it up to a classroom discussion. Last year I tried so many different strategies with them and this year we’re right back there with me hearing crickets even after I’ve asked them to talk with a partner first and then when we come back to the whole class discussion nothing happens . Feeling frustrated!

I’m not sure what you’ve tried so this might all be moot. I teach seniors as well. Most love talking but some prefer to hide. First off, I state the expectation that all must speak, especially if they are being graded as an individual and/or a group. I give lots of support prior to them speaking to help with confidence. I circulate around the groups and give feedback and support.

Depending on the activity, I do random picking of who starts talking. Pick a name randomly, etc. Then do not move forward until they have spoken. Also, asking open-ended questions instead of closed ones. I’m sure that’s what you’re doing.

Can you give a specific example of an activity that you do?

I’m a fan of random picking, but only if it’s truly random. I use TeacherKit, but there are other apps that allow you to enter all your students’ names and then select one at the tap of a button. That way, no one can claim they are “getting picked on.” When a reluctant or quieter student is selected, I am not the bad guy. “It’s not me, blame the gods” or “Fate picked you!” Humor helps defuse student angst at times.

We have a “Pot of Doom” in classes. Each stident’s name is written on a wooden lolly stick and places into the pot. If children aren’t volunteering answers then the teachers resorts to the pot of doom. Humorous and productive at the same time as it gets them putting their hands up sooner.

This I love – definitely going to use.

Model to them how to have a discussion. Give them sentence starters and have them each write a reply, swap papers and respond back and forth. Have them pretend they are in a meeting and the “boss” needs something done ASAP. I tell my 8th graders they are getting ready for the real world whether it is high school, college, or going out to get a job.

Have your students respond in writing. Then ask for the non-participators to share what they wrote. It might spur some conversation. Of course I have to heed my own advice!

I am currently teaching the Freshmen 9th grade at a public school in Micronesia. Sometimes it gets into my nerves if they are not paying attention and doing other things like talking about something else so I switch them to another activity like solving crossword puzzles and other games about word power please give me some suggestions that can make them stop talking and focus on what they should do. I give them magazines, pocketbooks to read so that they will be busy during classes. English Class Yap High School

Olivia, if you haven’t already, take a look at the section of the post called “The Solution.” Jenn outlines a five step process that might be useful for decreasing off-task conversations and encouraging students to focus on the learning activity. You also might want to check out some of the other posts related to behavior management on the site. I hope this helps!

Have you thought of having them write down their answers in a journaling-type of discussion. Then you should be able to call on anyone. I have had this problem in both middle school and high school classes. I find that students participate less and less as they get older. If you come up with different ways for them to share their answers (through journaling, writing on sticky notes, having them write their answers on the board, etc.) they are more willing to share.

Hi Carol,

I’ve taught quite a few of those types of classes. One way of getting all student opinions / ideas out is to use mini-whiteboards. That way they discuss with their neighbour, then they have to come up with an answer because you need to see it on their whiteboards when they hold them up.

This also helps them feel less awkward giving an answer; they’ve discussed it in pairs and they do not feel “put on the spot” on their own.

When continuing their ideas into a class discussion; that is the hardest part and I have not come up with any great solutions for that other than to have them work in smaller groups.

Good luck!

Perhaps you could explain that each pair will share their discussion with the class, and then use a name picker app to select students to share. I’ve also found that contradicting a student quickly ignites conversation, especially from those students who agree with the student. Good luck!

Thank you for the great article. Wondering how this would apply with students with 504’s and/or IEP’s who have trouble staying focused. I’m thinking an additional layer of signals between teacher and student?

Hi, Audrey. Here’s an article to check out from Smart Classroom Management. You may find some helpful tips.

Thank you for these explicit steps to dealing with this tricky classroom issue. Just this week a teacher brought this up in a coaching session. I’m excited to share this post with her; to learn alongside and to support her and the students in the process.

I have a different situation. This year I landed in a school that, unbeknownst to me, has absolutely no discipline plan at all. All the teachers talk over their students and give directions, so nobody can clearly hear anything, and no student is actually required to listen and follow directions. The school is also big on earning points for good behavior, except that everyone gets points for everything, so… I used Mr. Linsin’s techniques in my previous school. His “When I say go” approach to directions is really effective, but I’ve already been told not to use it this year. I’m stuck. But thanks for the reminder about this effective approach to teaching/learning appropriate behavior.

Thank you so much for this podcast. This year I am struggling with talkative students (new school/new teacher). I know I let the ball drop in too many areas…plan on fixing tomorrow. Thank you.

I found this post helpful, but as for Michael Linsin’s website that is promoted here, I found it highly problematic. The first two posts on his site that I cam across were steeped in whiteness and not sending the message that culturally relevant practice is the goal. The first post asks what to do when students question you “When you know they’re just trying to get under your skin.” How can we possibly know that a student questioning us is not actually valid because we are not teaching them in a way they need to be taught? I think this is a very dangerous ideology to be putting out there for a country of majority white educators. His next post was “How To Handle Disrespectful Students Who Don’t Know They’re Being Disrespectful” Don’t know they’re being disrespectful? Then they’re not being disrespectful! Not adhering to white cultural norms is not necessarily disrespect. This quote put me over the edge:

“Disrespect appears to be on the rise—particularly among younger students. It’s important, however, to determine if the disrespect is intentional or a misunderstanding of the definition.

Sadly, as surprising as it may seem, due to poor home and neighborhood influences many students just don’t know any better.”

To promote a website that thinks and speaks this way about our students is harmful. We can explicitly teach our students what appropriate and inappropriate behavior look like in our classroom (after having examined the role and presence of whiteness in what we deem appropriate and inappropriate), but to label other behaviors as a misunderstanding of the definition of disrespect? There is no one definition of disrespect. That is code for misunderstanding the dominant white definition of disrespect.

Hi Elicia,

I let this sit in moderation for a few days, waiting to find the time to write a thoughtful response.

First of all, thank you for taking the time to share your concerns here. I think it’s important for all of us as educators to stay open to criticism and continue to grow, and the only way we can do that is to invite differing opinions. In all of the the posts I’ve read on Smart Classroom Management, I never saw anything that struck me as culturally insensitive. Michael’s approach has always been one of calm, respectful de-escalation, of not calling students out publicly, and of being clear with expectations and consistent in their implementation. In fact, the criticisms I’m used to seeing of his site are from teachers who don’t like the fact that he puts so much responsibility for classroom management on the teacher, when they feel students should share more of the responsibility. With that said, I often miss these things, as my privilege hasn’t given me much of a critical eye, so I don’t want to discount your concern.

I think it’s interesting how people view things differently depending on their own lenses. When I read the examples of students being disrespectful in the article you referenced, I pictured white kids. In fact, throughout the whole article, I was picturing kids who have few rules at home and are kind of coddled by parents. And in my mind, those kids were privileged and white. So the notion that there was an underlying message of enforcing cultural norms never occurred to me.

With that said, my own awareness has grown in the last year of how white-centered so much of our culture is, so I want to leave room for that possibility on my own site, on Michael’s, and in plenty of other education spaces. I would like to hear what others think about this.

I’m replying to this as a teacher. I have taught in title 1 schools my entire life. FIRSTLY, how could you say it “sounds like white kids?” as an educator you are supposed to have all students held to a high standards. You talk about “culture”, education is wide spread to help all students out of poverty. You keep bring up race in education. I have never worked at a school with only a certain race base. Poverty is a cycle and not race based. I’m sorry, I do agree with you, these tactics may not be best for the school you are at. The school I teach at all students are held to the same educational standard, despite race, economic background , learning style, ect. All students should respect the teacher, you are there to help them. Not to judge them.

Hi Christina,

My comment was that when I read the article on Linsin’s site, I was *picturing* white students, not that they *sounded* white. My point was that we all read things from different perspectives. The fact that Elicia saw culturally insensitive, white-centric teaching in that article made me think she was picturing a more racially diverse class of students, and I can see how this would result in a different interpretation.

I’ll try to respond to this part: “You keep bring up race in education. I have never worked at a school with only a certain race base. Poverty is a cycle and not race based.” I’m not sure what you’re referring to, but I assume it might be some other articles on this site? If you don’t think race has an impact on education, then we definitely disagree here. For starters, I would recommend you read this article, and listen to my podcast interviews with Monique Morris and Dena Simmons.

The way that I read the article on disrespect is that whatever the particular culture finds respectful or disrespectful needs to be taught to the students. I moved around a lot growing up including outside of the United States and learned about other cultures ideas of respect and disrespect. In one culture I lived in, it was VERY disrespectful to touch someone’s hair. It is very possible for a student to have no clue they are being disrespectful if they are from a different area or if they are a student who needs to be specifically taught how to socialize well with others. I can’t say if Michael Linsin had white people in mind when he wroteit or not. However, I thought the main idea could be taken and adapted to any culture. I always appreciated when someone explained to me what not to do or to do when I moved to a new culture.

Thanks for bringing up your thoughts and ideas. I found them interesting and helped me look at the article from another point of view.

Why is everything about white privilege? Why can’t we be united and agree on what disrespect looks like. This isn’t a black white issue. It’s a human issue.

Mm:

Right on. Quit dragging it down, when all we really should be looking at is the concept of disrespect. When all children grow up they have to function in society based on ONE level of respect; not various ideologies. Golden Rule is my motto. Treat others as you want to be treated. The respect will follow.

Enjoyed your listening to your interview with Michael Linsin. Some good points and suggestions. I especially liked the “sign” to classmates.

My school has many second language learners and we use peer tutoring as a highly effective linguistic accommodation. So many times a student may ask her assigned peer tutor for help during direct teaching time. This could lead to others talking. Do you have any suggestions for managing this situation?

Hi, Teresa. I’m thinking the sign strategy (under Step 2) could work really well during direct instruction as well.

This is a problem on our entire intermediate floor. Teachers have taught and retaught expectations, some more than others, and yet the problem persists. One of the issues we have is students’ proximity to one another. We have 29-34 students in each room with just enough desks to accommodate them and little to no room for anything else. They are on top of each other ALL day long, no matter what room they are in. When permitted to talk in group or partner work, volume then becomes an issue. Looking for any ideas/suggestions.

Hi, Aimee. You may want to check out Michael Linsin’s article, How to Manage Large Class Sizes.

This was a fabulous article. So many practical tips/suggestions.

I feel crushed this year even though it is my third. I will give an honest attempt today at these steps and hope it bares fruit because the way things are going now are so soul crushing.

Andrew,

I’m so sorry to hear this – teaching is hard enough, without the added challenges of classroom mangagement. Even as a veteran teacher, I was always needing to re-examine my management, whether it was based on my group of kids, changes in my practice, or just whatever it was that was working or not in any given situation. Having said that, there are some foundational things to put in place that can be highly effective. This post has some great suggestions. In addition, if you haven’t already, be sure to check out the many other classroom management articles posted on the site, as well as one of my favorite books, How to Talk So Kids Can Learn. Be patient with yourself – remember to make any changes in small chunks. And try to find those marigolds for some possible support!

Perfect ideas!!! I just started my teaching career this year and this is perfectly helping me to gain control of a class and manage their behavior.

Great article, thank you for sharing your content and good will – I’m loving it! I’m still very new to the calling but keen to try some of these strategies.

My only concern with this is the dynamic of the classroom. You state that if several in your class is misbehaving, it’s on you the teacher. I disagree with this statement. It’s like when someone says a teacher has too many F’s in their classroom. If a teacher is utilizing a variety of strategies and making the appropriate accommodations, then the students are choosing to fail themselves. I have 5 bells a day. This past year I had 4 classes where I carried out my classroom policies and rarely had issues. This was not the case for my other class. Here’s something that has been discussed in my department frequently as an ongoing issue:

When you have a class with so many 504’s and IEP’s that don’t allow consistency and make their behaviors excusable, the whole classroom dynamic breaks down because you as the teacher have to honor the exceptionalities outlined in these legal documents. So many students can’t work independently and need assistance and clarification every step of the way. Many have ADHD and other disorders that make it hard for them to focus and not act out. It makes the classroom become very difficult to control when several students literally cannot help it and the documentation protects them from discipline. I respect all reasons of course, but it really strains the classroom dynamic, especially when you have 2 other adults in the room and have to maintain inclusion by keeping all students in the classroom. I get one or two classes like this every year and it becomes very challenging to handle.

When students are choosing not to respect, there’s a consequence for the students. When students do not do the work, they should fail and be held back because they chose to fail. Regardless of how effective teachers are in carrying out lessons and preparing materials, any teacher could get a class that just does not click or a few students that cannot comply with the expectations for behavior and/or academics. That should not be a part of their evaluation. I’ve been fortunate to have high marks on classroom management because I have been observed with my more well behaved classes.

Thanks for reading my concern. The teacher doesn’t exclusively hold the power here. I know veteran teachers that have had rough classes the entire year.

You bring up some very real concerns and sound like a teacher who does all she can to help her students, especially under some very challenging circumstances. I think Michael Linsin would agree that students, not the teacher, are responsible for their behavior. My understanding is that this post described a classroom in which the majority of kids in the class were no longer doing what they’d been previously taught and rather than sitting back and blaming the kids for this, it was “on the teacher” to kinda hit “reset.” I’ve been in those situations and would have to agree. My classroom management started out really strong, expectations were taught, practiced, and enforced. Then things got comfortable, winter came along, kids got antsy, and I got a bit more laid back. I was exhausted. Before I knew it, the class was a bit more out of control. I grew more frustrated and wanted to blame them for talking too much. After all, they knew what they were supposed to do. But in reality, I agree it was on me to take some steps back and reteach expectations. Maybe slow down. When I did this, things got back on track. It sounds like you already do these kinds of things. Some of the issues you brought up go beyond the scope of this post but would make for good discussion.

This is one of the most helpful teaching posts I’ve read. After re-entering the classroom following 15 years running newspapers, I am struggling to maintain control of my classroom. This is not an area in which I had issues previously. The dynamic has changed overall (the definitions of respect and privilege for teens), and for the first time I am in a Title I non-integrated school as a minority ethnic teacher. The point the author of the article makes about students who come into the class having been held (and currently are being held) to various expectations in other classes (using culture as the normative reason) is a large determining factor of whether these students trust and accept my leadership. Since I teach English, it is imperative there is some instructional time, and yet I am typically asked by conforming students to continue to teach over the conversations of others rather than wait for silence or to correct misbehavior. It is frustrating, but this article will help, not only personally, but in sharing with administrators as to the variety of discipline strategies we expect of our teachers. Thank you!

I really like how you teach students how to respond to other students when they are supposed to be silent. “But she/he talked to me first!” is a response I hear often when addressing student talking in class.

It seems that in your example of your classroom, many of your students started talking during silent independent practice because they needed help, and you couldn’t get to them before they stopped working. This is something that happens often in my class as well. How have you changed the structure of your independent practice so that students have access to the support and resources they need silently?

I have done these to various degrees of success:

1) I taped the class noise and played it back in the next lesson as a preemptive measure.

2) I sat down on the floor with some boys and hear them talk. Then I wrote a transcript of what they said and gave it to read to clarify if what I heard was correctly written.

3) I addressed each drift in conversations by saying,

“Let’s all hear what ___ has yo say.”

“Share your conversation with the class.”

“I listen when you are talking. But you are listening to me when I am talking!”

4) Talk in increasing speed and then suddenly keep quiet.

5) Tell the class, “If we go on like this, we all lose out. I lose as a teacher. You lose as students. We all lose.”

Amazing and very helpful.. thank you very much

I would like to have suggestions from elementary school teachers on what a consequence looks like for excessive talking. My children keep ending up with teachers who believe walking laps is an appropriate method even though it is against county and state policy. I keep taking an issue with it and yet it continues. I am a former teacher and never thought that making students walk laps would solve any classroom problems, especially excessive chatter. Are there any suggestions that may be helpful that do not include physical exercise as a punishment?

Hi there! As an elementary teacher myself (retired), this isn’t something that I’ve come across. You mentioned that your children keep getting teachers who believe walking laps is appropriate even though it’s against policy. If this is the case, I’m wondering if it’s some sort of school “policy” that the staff has agreed upon. Have you talked to just the teachers or admin as well? And has the rationale been clearly explained? I ask this because we know that kids need to move, talk and have breaks. Is it possible that walking the laps is more of a break or intervention so that when students return to class it’s easier to get back to work and focus? If this isn’t the case, then I think there are some other things teachers can do.

As with any kind of behavior that is self-distracting or distracting to others, I’d suggest putting support systems in place. The teacher can give kids an opportunity to talk out ideas within the group and/or partners for 5-10 minutes before going off to a private place for independent work. The teacher can let kids know ahead of time when they will have opportunities to talk/share. For example, explain they’ll be working independently for 20 minutes and then they’ll meet with a small group to talk about and share their work or ask questions and get help. Teachers can have individual conferences with students and include them in the problem solving process. They can also make simple statements like, “I’m having a hard time thinking right now. Please find a way that you can help me out,” and then be sure to follow with a, “Thanks so much.” There will always be exceptions, but overall, the intent is to understand what kids need and to help them be part of the problem solving process. If you haven’t already, check out How to Talk So Kids Can Learn. Hope this is somewhat helpful.

I find that these tips are great, especially about being very specific with your details and expectations, but some of them seem more fitted for younger kids? Does anyone have any tips on what we could use for a high school level? I find that my students do feel comfortable with me and we have a great relationship but unfortunately, part of high school culture is talking and it is extremely difficult to stop during instructions without making them feel like their voices aren’t silenced themselves. Any tips?

Claudia, Michael has a guide that’s specific to high school students available here.

I would like to ask about motivation. I haven’t seen anyone mentioning motivation as a factor that influences students’ behavior. And it does. If a student is bored, she/he will use different “tactics” to sabotage the class, excessive talking being just one of them. So I think that real challenge lies in our ability to motivate kids (or grown-ups), to capture their attention during the class, and try to get them interested. And as Gerald Huether says – you cannot educate someone by force, it’s neurologically impossible. A person can only educate her-/himself, and only if they want to. What you can do, you can encourage them to want to educate themselves.

Darija,

Near the beginning of the post, check out the 2 caveats that I think pretty much align with your thinking. Without engaging work or a decent relationship with the student, the strategies in the post may not be as effective. Thanks for sharing!

I read this with interest because I have been told by my school that my classes are too noisy and I should get them to make less noise. Now I am hard of hearing and actually cant stand noise (I teach design and technology (shop) as you folk call it). Ive asked my colleagues who teach around and with me and they say they are not noisy, so what do I do? Please help because at the moment this is giving me sleepless nights and a lot of stress.

Hey Tim,

I’m sorry this is causing you so much stress. It sounds like you’re a bit confused with this feedback. Every teacher is different, but the one thing that I always considered is whether or not the noise level in my room was related to learning. Was it productive? Was it part of collaboration? Did it lead to new ideas and problem solving? Did it interfere with the needs of myself or others? There’s a reason you were asked to lessen the noise in your room. (I’m assuming this was a request by administration.) Maybe start by taking some time to really observe the “kind” of noise that’s occuring. Maybe even ask or survey your kids to see what they think. If in the end, you are still concerned with the feedback you received, I might just ask for more clarification — not in a defensive way — but just so you have an opportunity to better understand and share your observations as well. Hope this helps.

I enjoyed reading this article. I am in my third year of teaching in a special education classroom and have for the most part had the same group of children. My scholars and I have a very close loving relationship and respect each other. They are very chatty during instructional times and independent work times. I like the model your expectations approach and look forward to introducing this in my classroom tomorrow. It would be like a practice what you teach and expect.

I’m sorry but this article is bull. Has the author or interviewee actually taught high needs students at a public school in the real world? I work at a high poverty Title 1 school and students are all over the place. I would say some students want to be respectful but even after decent student relationships and consistently enforcing consequences for chronic overtalkers, parents don’t care and blame the teacher as ineffective. No matter how many times teachers go over expectations and modelling, excessive talking and interrupting keeps happening.

In language arts, my classroom management is very good. However, I can’t get my drama students to be quiet for anything, not before a scene, after a scene, during a scene, not during instruction, not a thing. I’m dying here. They signed up for this elective. They are wild and outgoing, but mostly before/after getting on stage!?! I’ve been doing this for 13 years, and I want to quit drama every year. I saw your post about it being me. Help!

Hey Jen,

13 years of wanting to quit Drama — that sounds like a pretty big (and frustrating) deal. Classroom management is one of the most challenging aspects of teaching, so with a course like Drama, which seems to lend itself to more socializing and high energy anyway, I’d think the challenges could be even greater. I’m not sure what kinds of things you’ve tried, but if you haven’t already, try reaching out to other colleagues/Drama teachers in the district or in a social media chat who may be able to offer some suggestions. Be sure to also check out the links in the article.

We have a lot of other resources in the Classroom Management board on Pinterest – see what’s relevant. Also take a look at the posts in the behavior management category on the site. Just try something – one thing to start out with that you think could make a pretty big difference. You can always continue to implement new routines or structures, but to avoid getting too overwhelmed, start with something that really resonates with you. Hope this helps!

Hi there!

I am wondering what can I do if I have strong personalities student’s and how can I help them

Hey Ari, that’s a good question. As a general rule, I think all of the tips offered in this post are good guidelines for whatever class you’re teaching. That being said, there are always students who pose teachers with more of a challenge. Students with strong personalities, for example, might be more difficult to manage in a classroom environment, but they also might be the ones to dominate class discussions. Here are some suggestions I found that could help you manage strong personalities in the classroom. Jenn’s post on the Fisheye Syndrome provides some additional direction on how to get equitable participation from students in your class.

I am a student teacher so classroom management is one of my biggest challenges and it something I am constantly trying to learn new strategies for, especially for one chatty class. I found this article very helpful and appreciated the practical tips. I would not have thought to explicitly explain what I mean by quiet, but I could hear myself in my head saying “It’s too loud in here” while I was reading this and I realize how unclear that actually is. I will be trying some of these strategies in my class this week and look forward to reading more here in the future.

Thank you so much for posting this and for sharing that you yelled. I’m a student teacher and I got really frustrated this week and yelled. I still feel badly. I just had no idea what else to do after telling them over and over again to be quiet, that this was independent work, not group work; that some students were really struggling to write because of the extreme noise level. I will be printing this off to have a reminder and start working on setting good expectations.

Thank you for all these useful ideas! I really liked that you pointed out having a good relationship with your students is important. Love your podcasts and blogs. As a future educator I have already learned so much from Cult of Pedagogy.

Thanks for sharing all your great ideas and tips. I agree that building a relationship with your students is one of the most important things you can do as a teacher. One thing I was reflecting on was the point shared from Linsin, “Your authority has faded. If you’re able to teach to a quiet classroom in the beginning of the year and now you’re not able to, or if it happened right off the bat, then somehow at some point, the students’ respect for you and for the process, for the classroom, and your authority has faded.” Something I wonder is how much time has been placed on building the classroom community. Not only the relationship with teacher and student, but how the classroom functions as a whole and the purpose of their time together. I have found that taking time to talk, share, practice, receive feedback and reflect on our contributions in the classroom community directly impacts student focus and the work they accomplish in a day. Much like how you refer to the students practicing what it looks like to be quiet, they can practice how to help themselves and their classmates learn. But I think even more important is the time you spend building purposeful and meaningful experiences for students. When you do this, they want to be thinking and working and showing their best effort because they are engaged and invested in the learning.

Hey,

I really need some advice. I only have classes once a week when the classroom teacher is off class.

So I have to do research tasks with the kids in a really big learning area at the same time that another class is also in this learning space with another teacher. But when they come to me they won’t stop talking at all and they have no interest in the task. I try to reward the main few culprits whenever they do something positive, but they just think of the rewards as a joke. I follow through with my behaviour system but they don’t care if they are in with me as break times.

I normally let the classes pick their own groups for research tasks but with one class I chose for them because they were so rude and noisy when I explained the task. They didn’t react well to this and they kept going over to the other class who was working on the other side of the room. I have no idea how to get them to take me seriously because they know they only have me for 1/2 an hour each week. But that 1/2 an hour feels like 3 hours. What can I do???

Hey Kylie,

I’m so sorry to hear your frustration – doesn’t sound like much fun. Classroom management is one of the biggest challenges teachers face. And it can be even harder when you don’t have the consistency to build those relationships. But it can still be done, for sure. On the site, we have a bunch of posts tagged behavior management – I suggest looking through those to see if something jumps out as a good place to start. 5 Questions to Ask Yourself About Unmotivated Studentsis one that covers a lot of things to reflect upon. You might also want to check out the resources on our Classroom Management Pinterest board. Hope this helps!

Hello,

You say that if the whole class is doing it, then its on us. However I see 4 different classes and I behave the exact same way for every class. 3 of the 4 do what I ask with the exception of a few. However, the 4th class, which is 6th graders continually talk when I am trying to give them a lesson even though every single time, I have told them clearly what I expect. I have given them different consequences every single time that I defined at the beginning and yet they still wont show me respect. I don’t understand! Especially when 3 or the 4 classes behave the same. Please explain how it is me!! I really would like an honest response. I’m at my wits end and don’t know what else to do. Please help!

Hi Heather,

It sounds like whatever systems you have in place in those 3 classes, are generally working really well. What stood out to me though is that you said you behave the same in all 4 classes, and the reality is, as you know, is that not all classes or make-up of classes are the same. You’re not alone. I had great classroom management for years…and then one year…Bam. Although I implemented the same procedures and routines as usual, and established really great relationships, the dynamics of the class were just different. I didn’t get it either, but I realized that it was on me to do something different, because what we were doing, wasn’t working. My kids were different. They had different needs than my other classes. They interacted differently. I needed to make adjustments; ultimately, I realized I needed to be more structured than usual and more than what I wanted. Not structured as in strict, but as in taking things more slowly. Breaking down tasks and directions into smaller chunks. It was challenging, but hitting reset and taking smaller steps really helped. The kids knew things weren’t working, so the changes didn’t come as a surprise. I think this is what Michael Linsin was saying – that “it’s on us teachers” to try something different. It doesn’t mean that it will be easy, but we can’t use the kids as an excuse to give up. And I don’t hear you saying that at all.

My suggestion is to take a look at the other articles on the site that are tagged “behavior management.” Even if you’ve seen them before, take another look with fresh eyes and see what catches your eye that might be relevant. Be sure to check out 5 Reasons You Should Seek Your Own Student Feedback. We also have a lot of resources on our Classroom Management Pinterest board. I hope this helps – hang in there!

Excellent article. Thank you!

I am a Paraprofesional right now , and it was so difficult for me to keep quiet the kids in my class room because they don’t know how to be in silent, all the time I have to be remain them with a signal to keep their voice down. I think maybe they are too younger, could you give me some advices, please to keep them quiet in the class room?

When my students talk while I’m teaching, I just stop and wait. If that doesn’t work, I post written instructions on my website and tell students to go there and read the directions.

I usually open every class with a riddle or fun anecdote – but if students won’t sit and listen quietly – I stop that practice for three or four days and go right into their assignment for the day – with written instructions and rubrics.

Most classes catch on and learn how to be quiet when I am speaking. For the classes who don’t catch on – lessons are much less fun and engaging. I give them the option and the power to choose which type of class they want to attend.

As a 2nd grade teacher, I had this exact same problem. I would get on to my students for talking when doing individual daily assignments. Most of my students don’t understand they have to work independently and want to work together. I also had moments when I would yell at them because they wouldn’t listen. A classroom management strategy I use in my classroom is color behavior. Green is good, yellow is a warning, orange is 5 minutes from recess or silent snack/lunch, and red is a talk with parents. Using this strategy helped me tremendously.

I agree that education courses seem to ignore how much students talk. But I think students need to talk sometimes. So I can see how a smaller classroom could help control them when they are talking.

This post was written quite a while ago, so I wonder if your thoughts have changed on this post. I think there is an overwhelming presumption in education that students talking is a bad thing because we as educators need to present them with information. This may work best in science, but I find that students learn more when we use a discovery-based approach that emphasizes the importance of students’ voices. I also believe that, generally, we as educators should be doing a lot less of the talking in the class.

Thank you for your content. I always appreciate your perspective.

Hi, Erin! This particular post is addressing “excessive talking,” or talking that occurs during independent work time or direct instruction. Students certainly need to talk and engage with each other in order to discover, learn, and grow. In fact, in the first section of the post Jenn offers the caveat that students need to talk with their peers and experience engaging work in the classroom environment.

Thanks for commenting! It’s great to hear from educators committed to honoring students’ voices!

I would like to demonstrate expectations but I can’t get them to be quiet even for that. How can I achieve good classroom expectations if they won’t listen while I am trying to teach the expectations?

Jim, that definitely sounds like a tough situation. Every classroom is different, but if you scroll through the other comments on this post, you’ll find some ideas that have worked for other readers in their own classrooms. You also might be interested in this Pinterest board, curated by Cult of Pedagogy, which has a ton of resources specifically about classroom management.

I am a student teacher and I have attempted to emphasize that I am still in charge even when my host teacher is out of the room. After reading this, I am going to work towards clearly defining what is expected of them and of myself. I will remember this post as I go into my first teaching job. Thank you!

Hi Brian,

It’s great to hear this has resonated with you. Best of luck to you in your teaching career!

When each class has three fire starters who can’t stand you, and their parents won’t respond, and administrators say they can’t do anything about mere defiance unless it involves the threat of physical harm, and there they are – spitefully working against everything you do. Yes, I’ve spent time, energy, and money trying to “build relationships” with them, but I’m told things by these kids daily that would make a sailor blush.

Steven,

I’m sure most teachers can relate. Sometimes it seems as if no matter what we do, there are situations beyond our control. That doesn’t mean relationships don’t matter, or that our efforts aren’t having an impact. Have you seen the post about Unpacking Trauma-Informed Teaching? There might be some ideas you might find useful.

I loved reading this article and listening to the podcast. This summer I had some real struggles with kids talking when they weren’t supposed to be talking. Definity would like to implement some of these things to try also, like how you spoke about understanding why they are doing it and not jumping to conclusions. Give them simple clues like what they should do and when and an example of some bad behaviors to show them how not to act. Have a question what can you do for the ones that have the learning disability or are on the spectrum to help them be quiet when they need to be?

Amber, I’m so glad that you enjoyed the post and the podcast episode! Addressing the specific needs of students with learning disabilities is one of the most complex aspects of teaching. Without knowing the individual needs of the students in your classroom, it will be tough to answer your question meaningfully in a blog comment. However, Jenn has several other posts on the site that pertain to topics related to special education. I would encourage you to take a look through some of them and see what resonates with you. I hope this gives you a good starting point!

Hi Amber, this is Andrea from Jenn’s team. It’s definitely helpful to acknowledge that common behavioral expectations are not always appropriate or applicable to students with disabilities and I think it’s great that you’re seeking ways to support your students. As a teacher myself, I understand the challenge of managing a classroom when students have varying abilities in terms of how long they’re able attend quietly to a lesson. I’ve learned not to take it personally or to think of it as bad behavior at all, but rather a manifestation of their disability. I’ve also incorporated inclusive techniques such as frequent breaks, collaborative, hands-on activities, flexible seating, and, of course, any accommodations found on their IEPs. For further reading, I recommend Jenn’s post . Feel free to reach out with follow-up questions if you still have them, and best of luck in the coming year!