Listen to the interview with Shveta Miller (transcript):

Sponsored by Learners Edge

This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

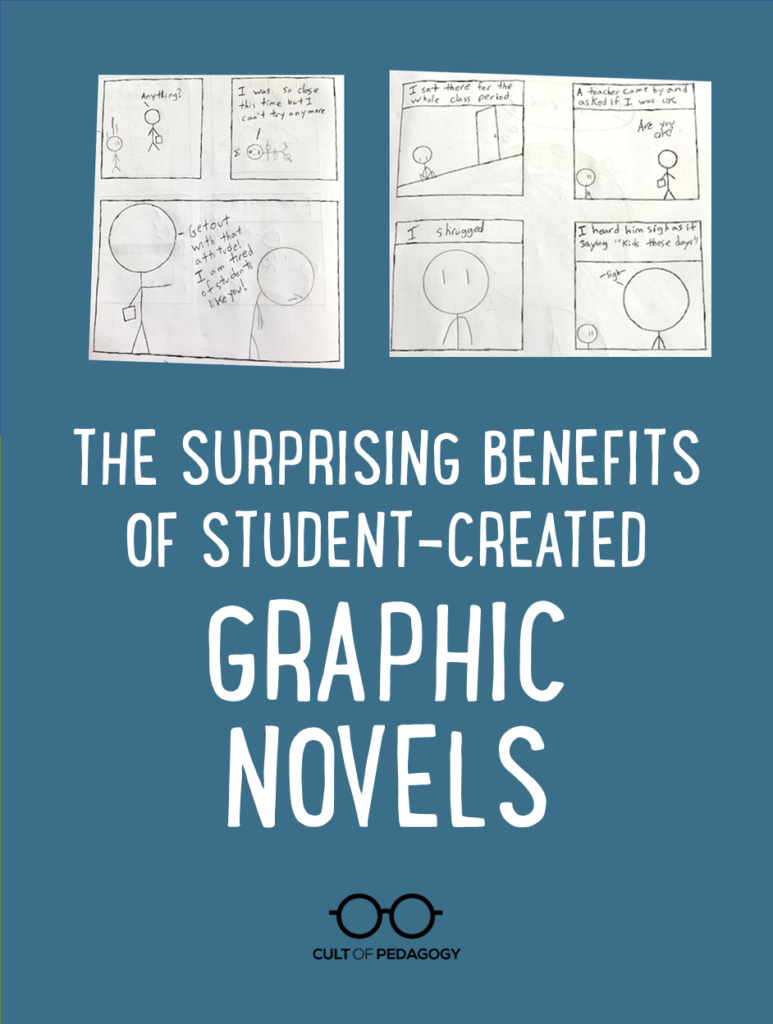

There is no shortage of ways we all can benefit from teaching graphic novels. They engage reluctant or struggling readers, they are gateway texts for more complex literature, they build necessary background knowledge, and they develop visual literacy skills.

But another important reason to teach students to read, analyze, and create a graphic novel is that the form invites them to express hard truths about themselves and their experiences in a way that is different from what they can do with pure prose.

And perhaps a more surprising reason is for the impact it can have on a teacher’s relationship with students. Teaching the graphic novel to my high school English students was a way for me to see that there was pain in my classroom and the role I might be playing in students’ difficult experiences.

How the Graphic Novel Form Inspires Deeply Personal Storytelling

I taught my first unit on the graphic novel in my high school World Literature classes. We read Marjane Satrapi’s graphic memoir Persepolis (Amazon | Bookshop.org), in which a young Marji describes her experience growing up in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. For their culminating project, students created their own graphic memoirs about a significant experience in their lives, using Persepolis as their mentor text.

As I turned page after page of each student’s story, I discovered that this unit had accomplished a goal I never intended. I didn’t expect so many students to delve into deeply personal, often traumatic, experiences from their past. I had read engaging personal narratives from students before, but this was different. Some used the project to announce an aspect of their identity they had kept secret. Others revealed the reasons behind certain challenging behaviors they exhibited in class. They created stories that would be healing for them and, in some cases, for their relationships with me.

What is it about the graphic novel form that made this possible?

Cartoons Invite Empathy

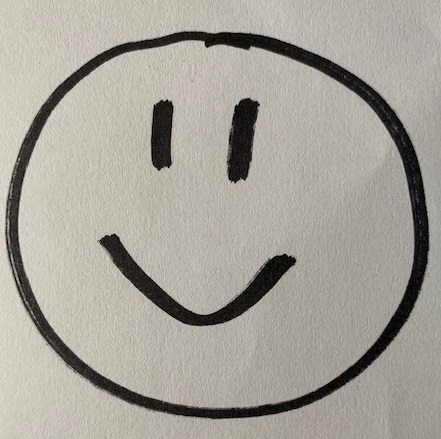

Anyone who has opened a comic or graphic novel before would immediately recognize that cartoon drawings are a defining feature of the medium. While a photograph or portrait tends towards realistic depiction, a cartoon leans more toward an abstract, iconic representation of a person, object, place, or idea. (Think of how a circle with two dots and a curve for a smile represents a happy person.)

In Understanding Comics (Amazon | Bookshop.org), Scott McCloud explains that when drawings of characters in graphic novels are less realistic and more iconic, readers can more easily put themselves in the situations of the characters. The cartoon image “is a vacuum into which our [the reader’s] identity and awareness are pulled” (36). A detailed drawing of a face with specific features would be harder for readers to identify with than a simplistic cartoon face. According to McCloud, if we are less focused on the specific details of the character’s drawing, then we are freer to enter the world of the character and participate in their experiences.

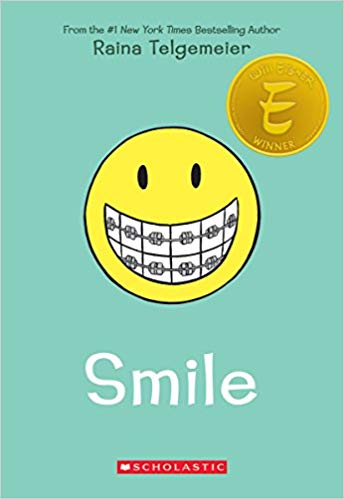

Graphic novelist Raina Telgemeier even explains that the creative team at Graphix “had the good intuition to use something more iconic” (20) for the cover image of her memoir Smile (Amazon | Bookshop.org). Instead of using a full-body drawing of the main character, they opted for something even more simplistically drawn: an emoji with braces. One can imagine that a more specific cover image of the book’s protagonist might not have instantly connected with as many book browsers as the abstracted emoji did.

So, if iconic images help readers empathize with characters’ experiences, then a graphic novelist who has traumatic events or complicated emotions to narrate can do so knowing that an empathetic readership awaits.

Cartoons Allow for Distance

And while the iconic images unique to comics and graphic novels allow readers to connect with characters (and, by proxy, the writers), the abstraction also allows the writer some distance from their emotional story. With very realistic drawings, or with prose narrative alone, sharing the experience might feel too revealing. The writer is less vulnerable, however, if their experience is portrayed with some abstraction. This didn’t happen to me specifically. This happens to lots of people. This is a universal experience.

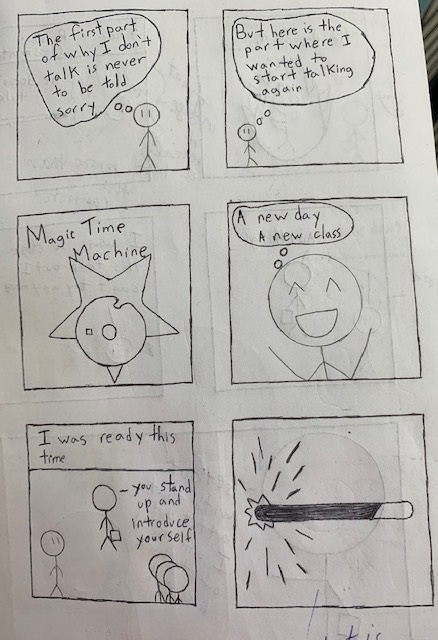

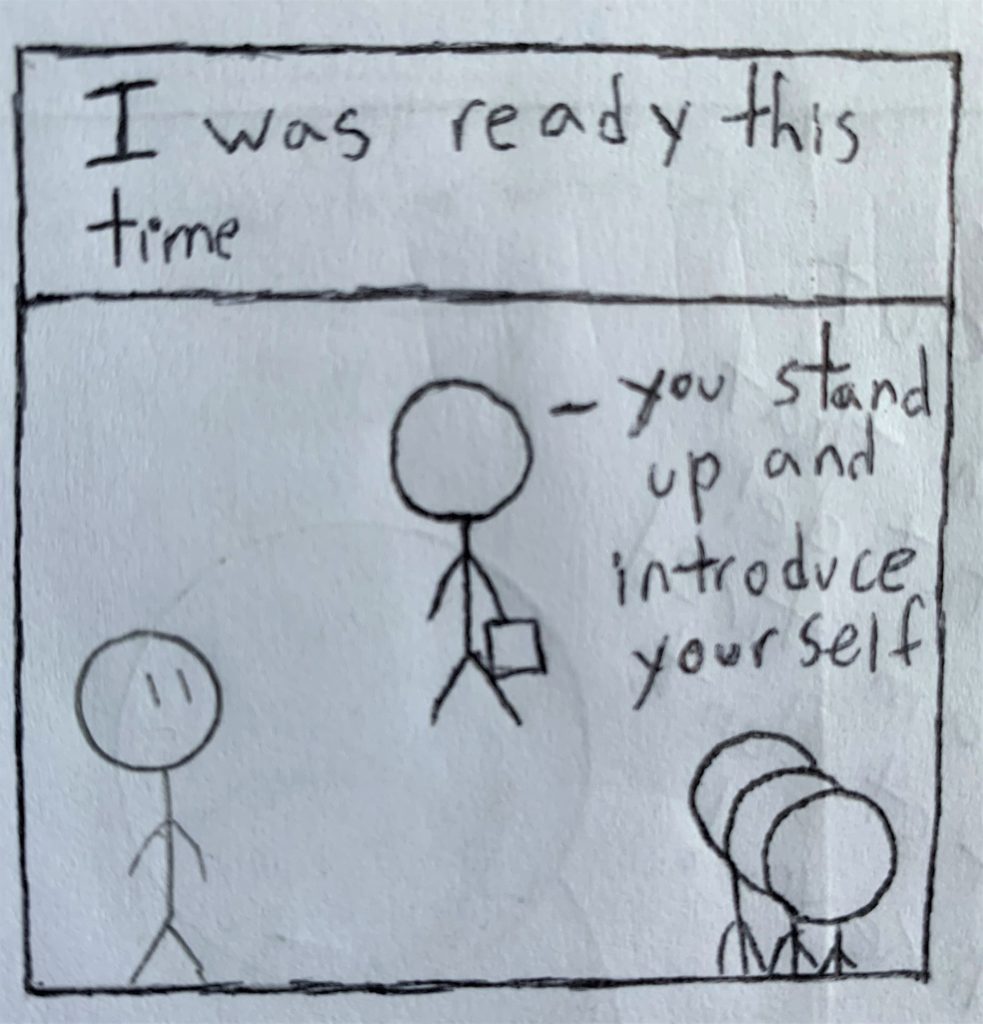

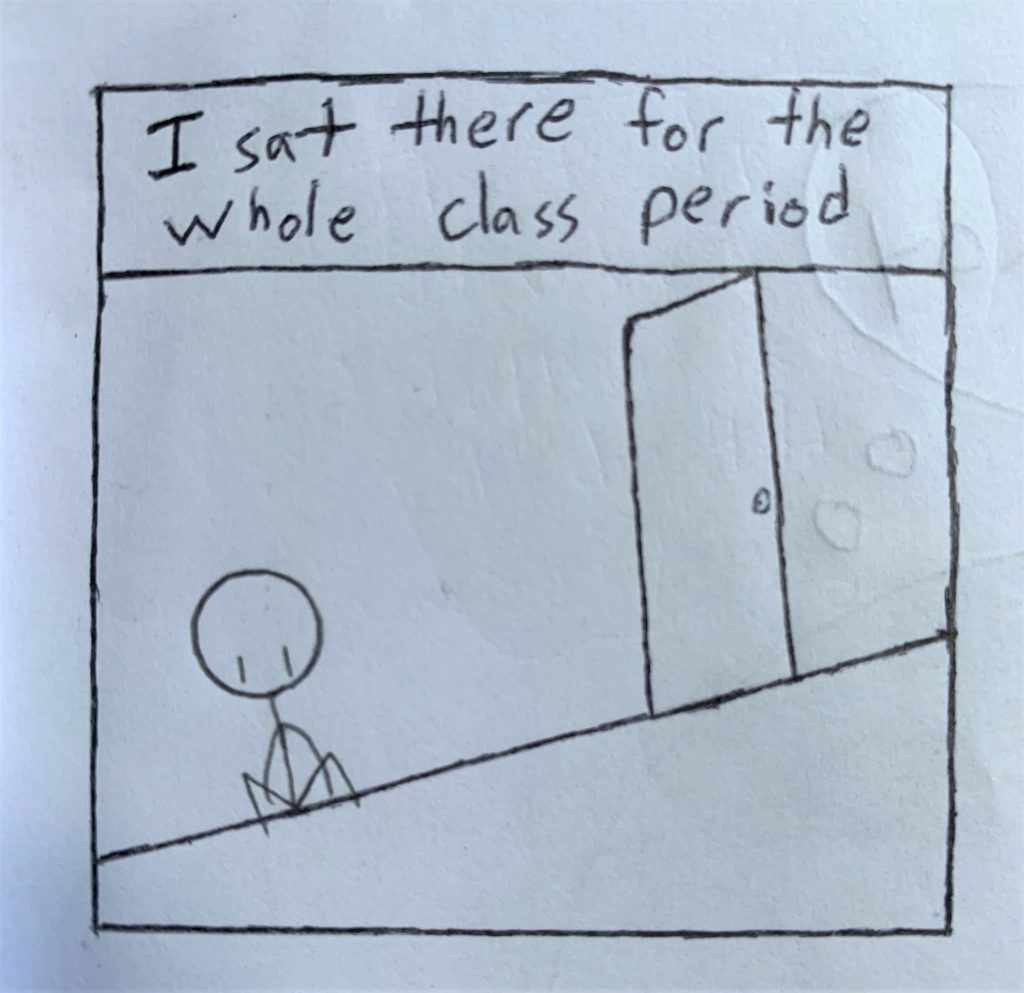

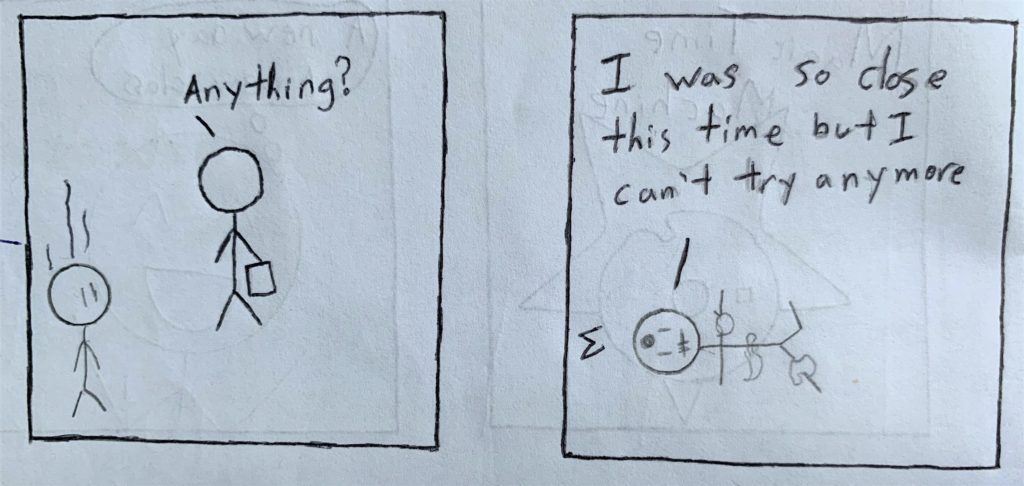

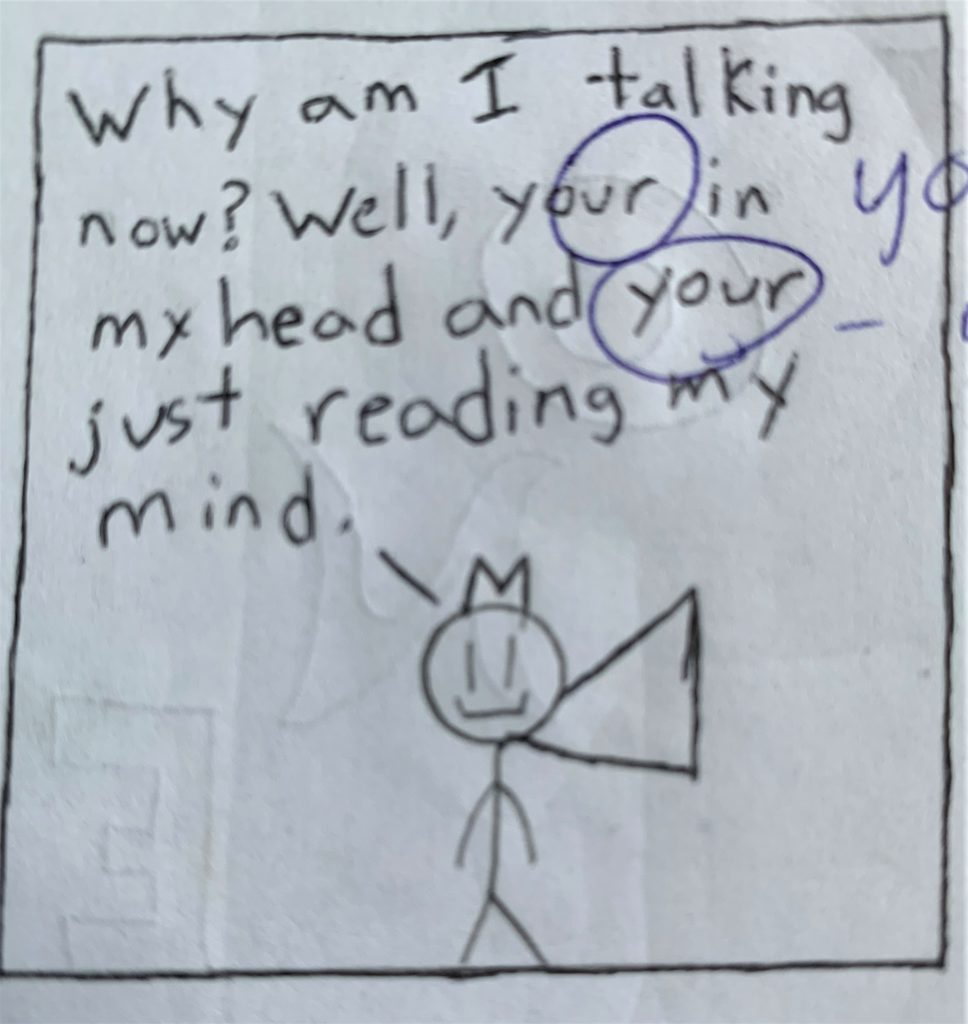

It makes sense to me, then, that a student of mine would use the most abstracted icons—stick figures—to share something especially private with our class in his own graphic novel, Spoken of One.

This student—I’ll call him Louis—was selectively mute all through high school. Sitting in the back row, completing all assigned written work but never raising his hand or contributing to partner interactions, Louis frustrated me. I had 36 students in my class, and I didn’t have the expertise to find ways to draw him out. It was easier to assign his partner to someone else, to simply not expect that Louis would participate since apparently he never had before.

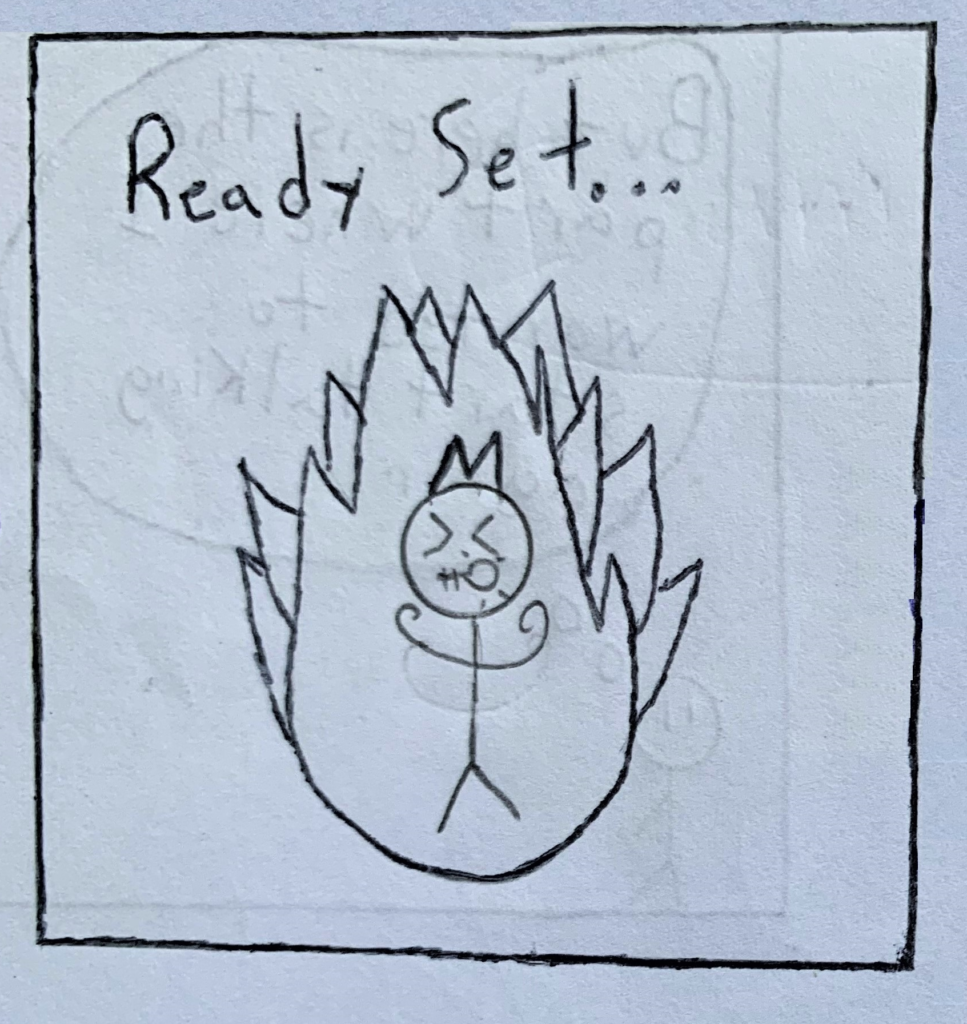

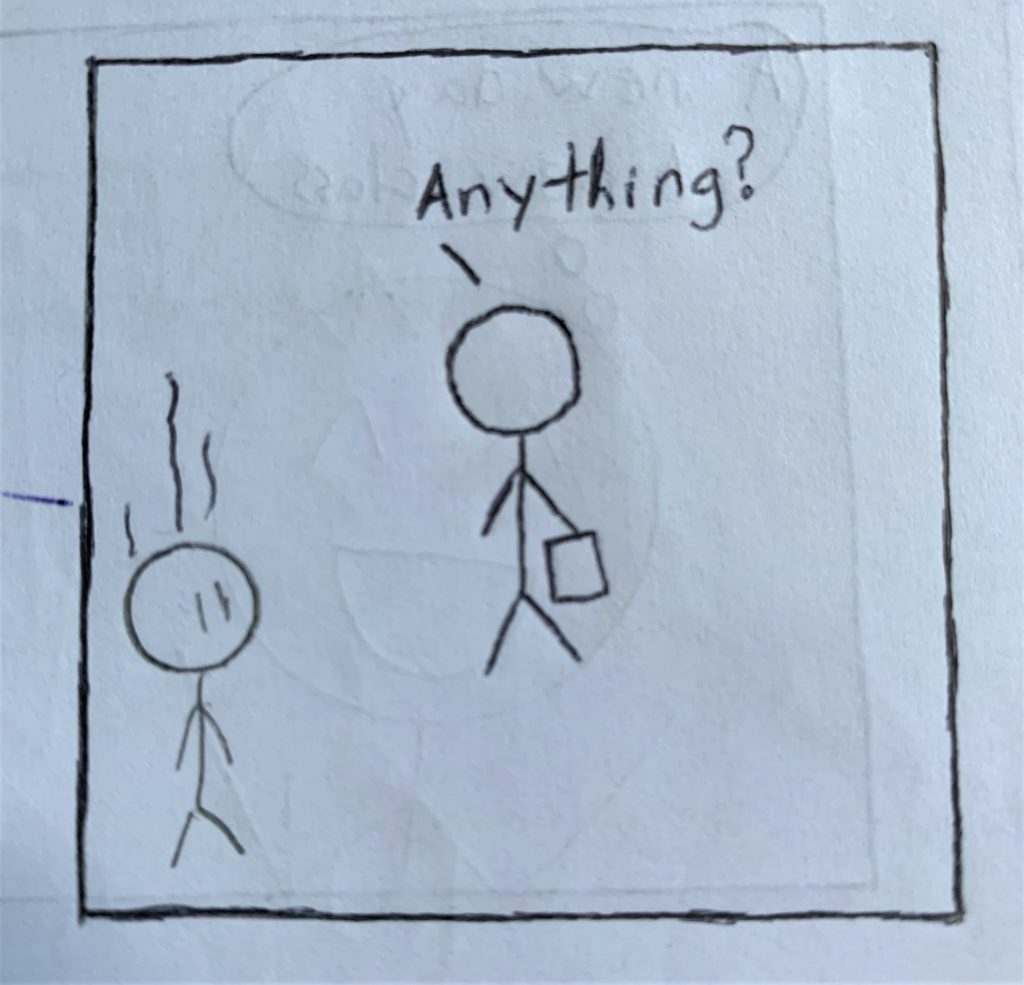

For the graphic novel project, Louis chose to communicate that he was making an effort to speak, but encountered debilitating obstacles like stigmatizing labels from peers and teachers.

With the anonymity offered by iconic representation, Louis perhaps felt safer in telling his story than he might have if he were asked to write a personal narrative. There is a comforting distance between his own identity and that of the universally drawn protagonist in his story. Maybe knowing that the reader could see the story more universally made it possible for him to share something so private.

Readers are Reflected in the Story

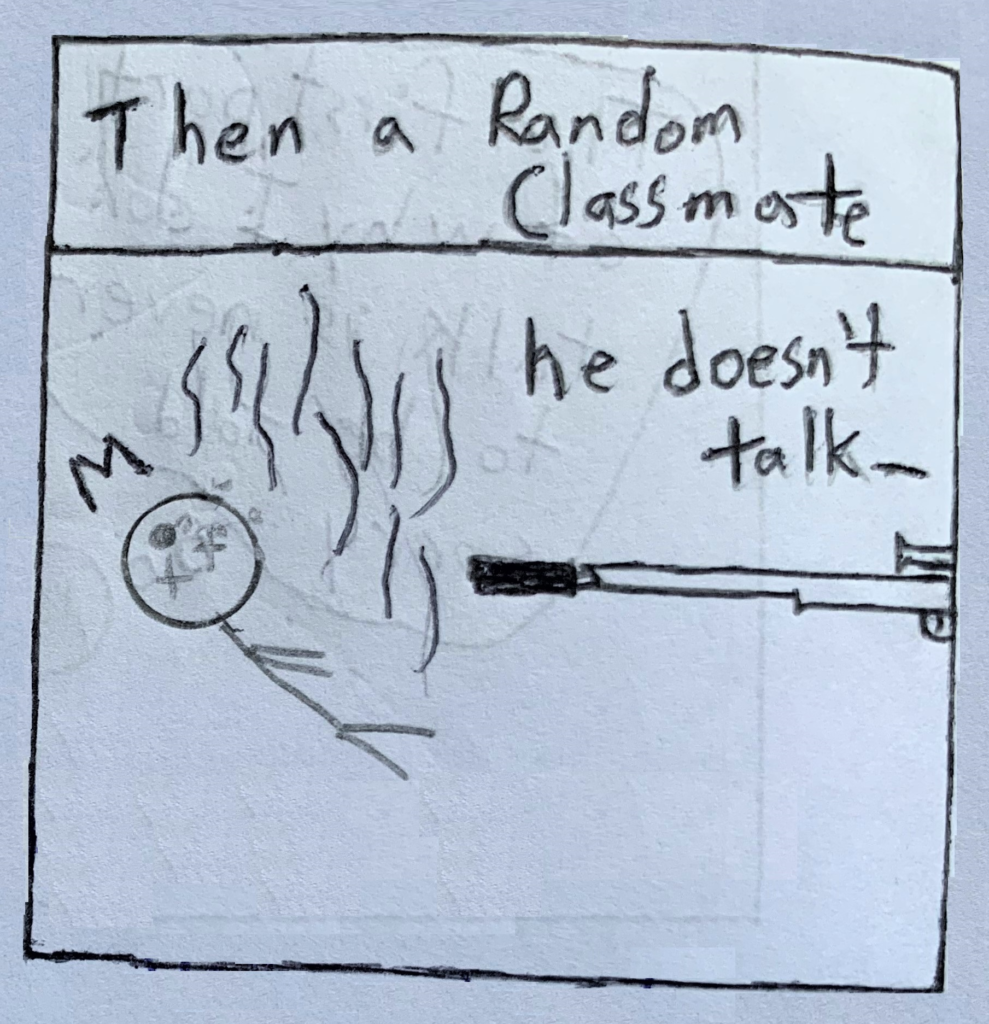

Louis knew that I would be reading these panels, but he also knew his classmates would read them during peer feedback. Perhaps the ease with which readers can identify with universal abstract icons might mean that his classmates and teacher would reflect on their own complicit actions in labeling him with declarations like “He doesn’t talk.” The simplicity of the nameless, faceless, abstract peers and teachers in this student’s panels invite my students and me to see ourselves.

When we move away from realistic representations and towards abstraction, McCloud explains, “we’re not so much eliminating details as we are focusing on specific details” (30). Louis draws teachers with such abstraction that the only distinguishing features are a simple square (representing a briefcase?), their position within a given panel (at a distance from students), and an absence of any facial markings (dots or lines for eyes, nose, mouth). Without being explicitly told what to see, readers can imagine their own rich details.

As a teacher, I could vividly see my own impatience with certain behaviors and the emotional weight that impatience had on my students. I thought my sighs were inaudible, my nonverbals (standing at a distance, unsympathetic facial expressions) unnoticeable. Maybe Louis wasn’t addressing me specifically in his panels, but that’s irrelevant. The iconic representation of people and events works like the “vacuum” McCloud describes, inviting me to reflect on my own complicity in Louis’ experience.

In another panel, the hallways of the school are stripped to the bare essentials: a white vacant floor on which to sulk. The specificity is so absent that a reader could “fill up” this iconic form with almost any other setting. The actual place, person, object, or idea being represented matters little.

Readers Must Help Tell the Story

Compelling texts are often ripe with ambiguity. Graphic novels, by their very design, contain “gaps” that readers must fill as they connect one panel to the next. By making connections and drawing conclusions in the gutters—the empty spaces between panels—the reader can help tell a story the writer can’t tell alone.

McCloud describes this reader participation as “committing closure,” and some transitions ask more of the reader than others. Many comics rely heavily on simple moment-to-moment and action-to-action transitions that require less participation (picture a person lifting a cup in one panel and drinking from it in the next). Others make powerful use of aspect-to-aspect and subject-to-subject transitions. These require readers to connect different experiences, time periods, and perspectives from one panel to the next. (Imagine a person lifting a cup in one panel and the next panel shows a different scene five years later).

In their own graphic novels, students generally struggle to create transitions that leave space for the reader to participate, but I think Louis found the gutter a helpful tool to tell his story without having to say too much.

What happens after the teacher prompts Louis to speak? How long does he pause before the next panel shows him defeated on the ground? How did his peers react? When I look at these two panels, I fill out the story: I hear his peers snickering, I see them rolling their eyes, my hands get sweaty thinking of how long the silence must have felt for this student compared to how brief it probably was to everyone else in the room.

It’s not that graphic novelists are off the hook from having to explain and narrate difficult moments. It’s that they are able to be selective with what they do show so that more readers can participate in ways that are personally relevant. And, I think that first learning about how gutters and transitions work in Persepolis, especially at certain difficult points in Marji’s story, encouraged students to include their own hard-to-describe experiences in their work. I don’t have to find words for every moment. I don’t have to show kids rolling their eyes. That can be for the reader to imagine in the gutter.

No Story is Too Complex

The combination of words and pictures helps writers communicate hard stuff—no story is too complex to tell with this medium. Comics have a long history of teaching complex subject matter. There are graphic novels that discuss scientific phenomena, race, gender, cancer, and mental health. Satrapi catches us up on thousands of years of Persian history through carefully composed panels. Some of my students were able to portray subtle racial and gender-based microaggressions they experienced without even needing to know the term “microaggression.” Others described complex learning disabilities and mental health issues without using a clinical vocabulary.

And because of the ability to “control time” (as comics expert Will Eisner puts it), the stories we tell in graphic novels are open to a wider readership. Young or inexperienced readers can make meaning from panels without necessarily drawing sophisticated conclusions from the gutters. As Gene Luen Yang explains (via McCloud), “Time within a comic book progresses only as quickly as the reader moves her eyes across the page. The pace at which information is transmitted is completely determined by the reader … this ‘visual permanence’ firmly places control over the pace of education in the hands (and eyes) of the student.”

Since readers of all ages and backgrounds can participate in reading graphic novels, my student writers could share sensitive stories with a variety of people in their lives, not just their teacher.

How I Taught This

To initially learn about the form of graphic novels, I read McCloud’s Understanding Comics, which provides a thorough explanation of the variety of elements and devices at work in a comic or graphic novel. Over the years, I also studied Will Eisner’s books Comics and Sequential Art (Amazon | Bookshop.org) and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative (Amazon | Bookshop.org).

To choose a mentor text for my 11th grade World Literature classes, I considered what would be grade-level appropriate and rich enough in terms of the devices I had learned about. What will connect with students’ experiences but also expose them to new ideas or challenge their understanding about certain concepts? Satrapi’s Persepolis jumped out as the perfect option: Teenage Marji narrates her experiences navigating religious, political, and social conflicts during a tumultuous time in Iran’s history. When choosing your own text, you might also consider connections to social studies or science content students have learned. Or you might choose an adaptation of a text you’ve already read or to connect to a theme or genre you are teaching.

The Launch

Determine Prior Knowledge

I distribute a page from a graphic novel, not necessarily from the one I will teach, and ask, What is happening? How do you know? Students’ written responses show me how familiar they are with noticing the subtle devices at work to communicate meaning in a visual text. With this information, I can partner students more effectively during upcoming lessons and keep their starting point in mind as I consider the unit instruction, tasks, and outcomes. Students also see for themselves how well or ill-equipped they are to do this type of reading, which for some students makes them curious to learn how.

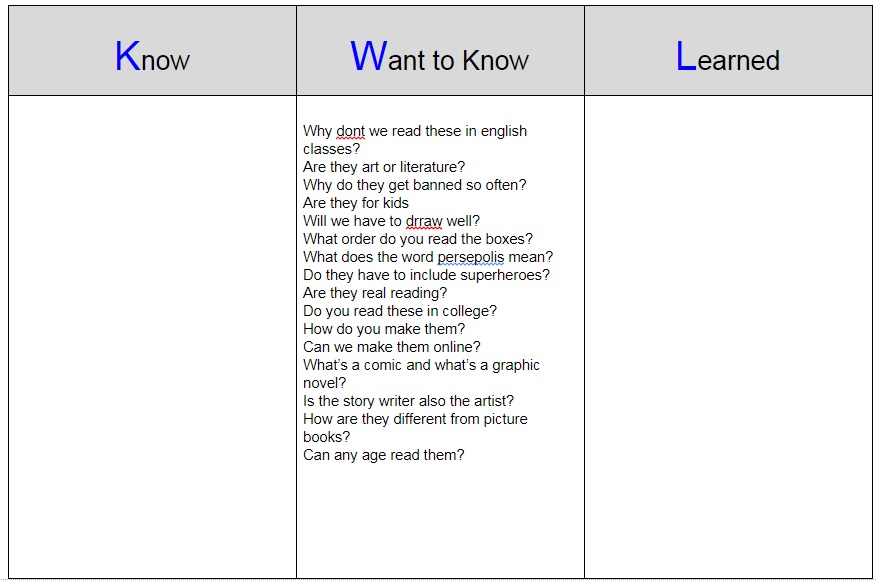

What do students want to know?

After attempting a close read of a graphic novel page, many students discover they either don’t have a lot to say or they know more than they thought. Then, they complete a KWL chart (Know-Want to Know-Learned) about graphic novels and Persepolis. My students have wondered, “How do you choose what to put in each box,” “Does the order you read matter,” and “Why is it called ‘Persepolis,’” The most exciting part of the chart is, of course, the “Learned” column that students complete at the end of the unit.

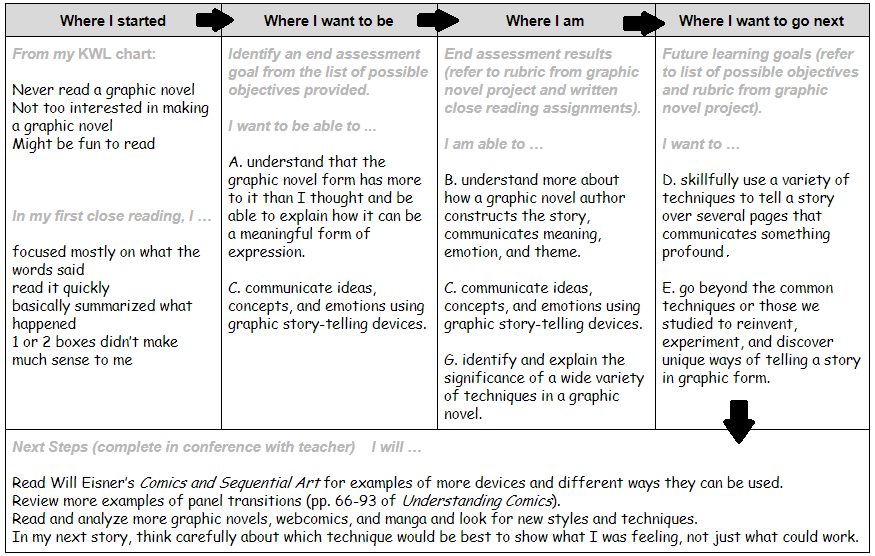

Personal Goals

At the beginning of the unit, students indicate “Where I started” and “Where I want to be.” I provide options of end objectives that students choose from. This tool is revisited at the end of the unit and students complete the “Where I am” and “Where I want to go next” columns as part of the assessment process (scroll down to “Assessing the Results” for an image of the chart). Because students articulate their own learning goals, ones that make sense given their starting point and the relevance of the topic to their lives, they are more invested in reaching those goals. And they often exceed them.

Build Background

Consider what context your students will need to know in order to understand the plot. For Persepolis, I provide a little background about the Islamic Revolution at the start. But most of it is learned as we read and encounter references we want to research, such as the philosophy of Karl Marx and what happened on Black Friday. Sometimes individual students are given the task of investigating a reference, and sometimes I present a few visuals or video to provide context.

Reading The Mentor Text

We read the novel mostly in class, with students working together to reread for deeper meaning. Before we discuss what we’ve read in class, students spend five minutes independently free-writing everything they notice from one page of Persepolis. I ask: What happened? How do you know? What have you learned about characters? With less time, students simply record one question they have about the assigned reading. In partners or small groups, they share their observations and questions and develop some consensus around how the page is working. Then they report their conclusions to the whole class.

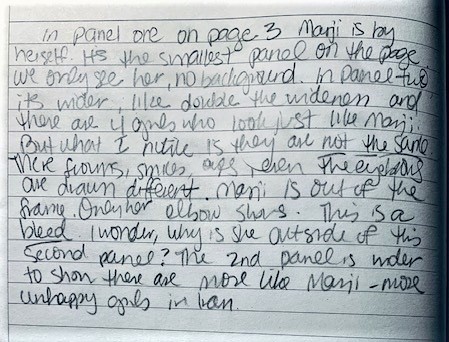

In whole class discussion, I introduce the terms and devices only after students have had the opportunity to express them in their own language. When they report that they know Marji feels weak because she’s drawn smaller than usual and she’s in a really small box, they learn to incorporate terms like “scale” and “frame.” When they notice a page has no panels, and the drawing fills up the entire page, they learn the term “splash.” When they notice one panel’s scene does not seem to connect to the one before and after, they learn to describe a variety of panel transitions with phrases like “action-to-action” and “subject-to-subject.”

Close Reading

To model close reading of graphic novels, I think aloud as I try to make meaning from one panel to the next. I use what I know about devices and techniques to pose questions, re-read, answer my own questions, and challenge my own answers. Students are then able to attempt astute readings of the text with partners, using the language I modeled.

For an example of how to model close reading of a graphic novel, watch me discuss page 6 of Persepolis with another reader in the video below. Reference this handout if you’d like to use the video as a teaching tool in your classroom.

Students are routinely asked to choose a panel to closely read and analyze in writing. I collect these as formative assessments that tell me if a device or specific page from the text needs review and if students are reading beyond the surface. Sometimes I provide a specific prompt, like “What do you think the author is communicating with the different uses of black and white in chapter 10?” or “Describe the significance of varying shapes and sizes of panels in chapter 1.” Other times, I solicit prompts from students or invite them to write about any discoveries they have made about the story and characters, supporting their observations with references to the techniques involved. For models of written close readings, I use previous students’ work, book reviews of graphic novels, and excerpts from Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art.

Practice

As we continue through the chapters of Persepolis, I post the terms we learned on chart papers around the room. Groups circulate and add examples of each from different chapters. Students who struggle to identify a certain device benefit from seeing examples posted by peers. And all students can see the variety of how one device could be used across different scenes for different purposes.

When student observations show me that a particular panel or page is challenging to understand, I post a copy of the pages on chart papers. Groups circulate and add their theories, questions, predictions, and interpretations. Meaning becomes evident through multiple reads of the page and collaborative discussion.

I use frequent but brief exercises that get students thinking about how the devices work in a graphic novel. For example, “If you had to show the emotion of fear with only lines, how would you draw them?” Or I might provide students with a sequence of panels with pictures but no captions and ask them to write the captions. Another day, I give them panels with only text and ask them to add the pictures. The key is to give the same panels to multiple students so they see the variety of ways they each interpreted specific text or visuals.

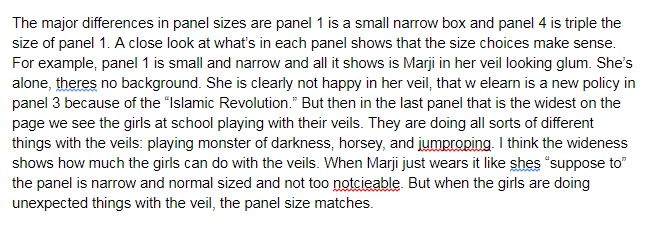

Use the Devices

An especially helpful activity is when students create their own panel using a technique or device they observe in a panel from Persepolis. In one panel, Marji’s family decides to stay in Tehran after an attack because access to a French education was important for Marji’s future. Satrapi composes the panel to emphasize the isolation Marji feels as her friends’ families fled. We see Marji from a bird’s eye view—only her back and her shadow. She is dwarfed by darkly colored trees that seem to replicate indefinitely, like she’s walking into a fun-house mirror. Where is Marji going? It’s unclear visually and also literally. Her future is unknown, and it’s scary.

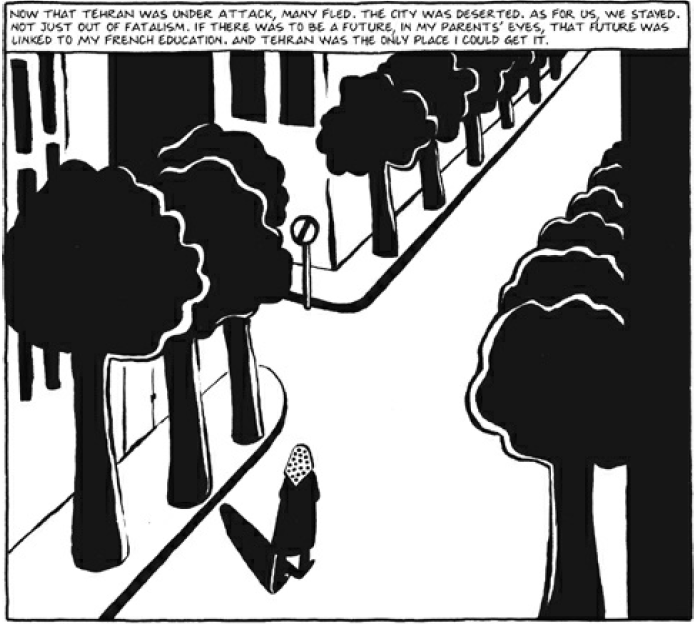

One student chose this specific panel’s techniques to try in his own panel. He connected Marji’s experience to his experience attending a new high school. The towering building, drawn with the same repetition as Satrapi’s trees, dwarfs my student, who changed schools also for access to a better education and preparation for some unknown future.

These “micro-writing” assignments help students learn the devices, but they also serve as early drafts of their final graphic novel projects and begin to convince even the most reluctant students that what we are learning is valuable.

The Culminating Project

The Assignment

Students use the tools and devices they learn from studying Persepolis to create a short graphic memoir about a significant experience in their lives. I ask each student to suggest one success criterion for this project, given what they have learned about what makes a graphic novel engaging.

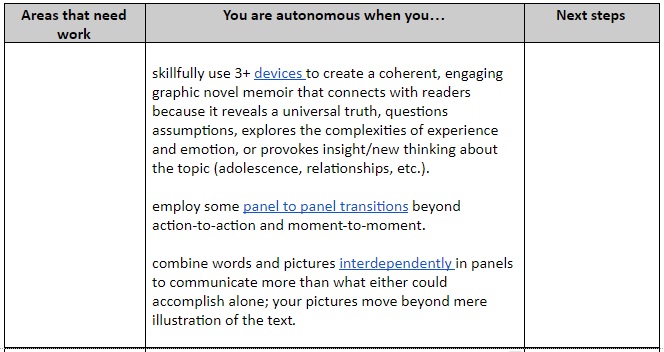

In the past, we have agreed that their stories would provoke thinking—more specifically, they would challenge assumptions, initiate a conversation, connect deeply with readers, and nudge them to act. To accomplish such worthy goals, they would need to skillfully use at least three devices, their words (captions and speech bubbles) would work interdependently with their pictures to communicate more than what either could accomplish alone, and some panel-to-panel transitions would move beyond moment-to-moment or action-to-action.

Drafting

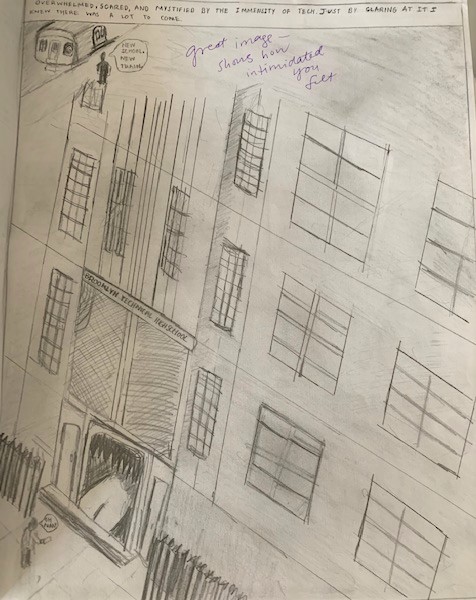

To decide on a topic, students reference their “micro-writing” assignments, create brainstorming lists of potential experiences, and free-write about each one. Students examine their most promising free-write and tease out a rising action, a climax, and resolution.

Then, students create a visual outline of each page, mapping out their ideas in a panel layout, describing what they plan to illustrate and why. They consider how they will distinguish their characters. They identify the emotions and moods they want to communicate for specific scenes and note devices that could help accomplish this.

I model this process at the start of class by attempting my own project, one panel at a time, in front of the class, thinking aloud and soliciting their help. A bonus is that my clear lack of artistic skills shows students that beautiful artwork is not necessary for this project. While sketching, I narrate, “I want to show this character feels bold and confident. I think I will remove the frame altogether (create a “splash”), or I could keep the frame and draw the character so large she goes beyond the border (a “bleed”).” At this point I ask for students’ input—which technique would be more effective and why.

Workshops

During the drafting process, students sign up to attend mini lessons, facilitated either by me or a peer, on topics like “creating captions and speech bubbles,” and “showing emotions with facial features and gestures.” I schedule two 20-minute mini lessons per workshop day. When students aren’t in the mini-lesson, they work on their panels independently, with support resources I provide (from Eisner, McCloud, and Barbara Slate). Topics for new mini-lessons are created in response to the challenges and needs students pose.

Review

Students have frequent opportunities to self-review their panels and pages in draft form before they commit to “inking” (finalizing and coloring). They ask themselves, Can I explain how I chose to create this panel? Have I considered the impact on the story if I were to change the panel-to-panel sequence, the words or pictures? Do my panels allow for reader participation (committing closure)? Am I finding this challenging? What do I need to know how to do? What/who can help me?

I don’t want to force students to share their personal stories with their classmates for peer review, so I ask them to choose at least one completed panel to share for feedback. Sometimes, I collect one panel from each student and anonymously re-distribute them to the class for feedback. As reviewers, students ask themselves, “What is happening? How do I know? What assumptions am I being asked to challenge? How I am I connecting with this story?” Their comments help the creator understand how readers are responding to their narrative and design choices.

Sometimes, students volunteer to share their pages with the whole class for feedback. I project the pages and we perform a close read like we have done so many times with the pages of Persepolis. Students who do not seize this opportunity to get such thorough feedback on their work still benefit from providing and listening to the feedback given for a peer’s work.

Assessing the Results

In the past, when I had scored these projects with As, I felt like I was sending a message that the learning was done. That their few-page attempts could just not be any better. But the goal is not that a student becomes a master at incorporating graphic elements into their own memoir after a few weeks of practice. The goal is that they have discovered a new form to explore with rigor beyond our classroom and have some creative independence with a new set of tools to tell all kinds of stories.

Instead of a four-point rubric that shows tiers of success leading up to the end goal of an A, 100, or “meets standards,” I decided to create a single-point rubric and define an “A” by listing what we agreed the project had to contain in order to demonstrate the student was ready to continue on their learning trajectory Autonomously. That means they would be prepared to independently and critically read graphic novels of different genres. They could start experimenting with devices, and maybe create their own, to communicate a range of experiences. They could research the work of other comics and comics movements, and learn the history of the form. They could connect with the larger world of graphic novelists by joining the conversation online.

The success criteria we established as a class allows students to focus primarily on their ability to use the graphic elements they studied to portray a significant event in their lives (not writing conventions or artistry). We do discuss how grammatical errors can really confuse the reader and how a hastily sketched image can ruin the effect of the device. The grammar and drawing expectations are in service of the larger goal and don’t need to be assessed with their own categories on the rubric. The focused criteria also help me avoid pitfalls of the past while providing feedback on students’ graphic novels, such as correcting grammar errors that didn’t actually impede understanding and praising artwork that didn’t actually develop the story.

Finally, students complete the “Learned” column of their KWL charts, proudly listing the discoveries they made about how to tell stories in a different way. They also reference their rubric feedback to respond to the last two columns on their Personal Goals form: “Where I am” and “Where I want to go next.” If students are not yet ready to pursue this work autonomously, what additional practice is needed? What resources can help? If they are ready for continued independent learning and practice, what books, websites, and writers can they explore? Students also have the option to continue working and resubmit their project for additional feedback later in the year.

Compared to my first attempt at assessment, this revised model communicated to students that the learning didn’t stop for anyone, even those with an A.

Why Teach Students How to Create a Graphic Novel?

After my first foray into teaching the graphic novel, I discovered that the benefits went beyond teaching literacy skills. Though the initial objective was for students to hone their close reading skills, it turned out that I also learned to read my students more closely, especially the ones I perceived as disengaged learners.

Without access to students’ stories, educators are likely to interpret certain behaviors as challenging. As Sarah MacLaughlin describes in an article about trauma-informed teaching, behaviors that have developed in response to a difficult home environment or experience can be interpreted as defiance in a class setting: “Trauma can manifest in so many behaviors! Hypervigilance can masquerade as hyperactivity… Fear can look like aggression: flight, freeze, or fight,” or in Louis’ case, selective mutism.

While reading my first class set of student-created graphic novels, I started to reconsider everything from my assessment practices to my nonverbal signals. I didn’t change into an enlightened, empathetic teacher overnight, but I started to approach interactions with students with the understanding that there were stories inside them that I wanted to hear, that I could make instructional decisions that would decrease cortisol and build relationships.

I know that without this project I would have continued to overlook Louis’ mutism. How would I have had such intimate access to a mute student’s perspective without his graphic novel? Louis put it so simply but elegantly on the first page, despite the grammatical error: “Why am I talking now? Well, your [sic] in my head and your just reading my mind.”

Teaching students to create graphic novels gives you the power to read their minds, which can change everything about the way you teach. More importantly, it gives them the power of voice—a superpower that can change their worlds. ♦️

Read the Book!!

Since writing this post, Shveta Miller has written a full-length book on this topic: Hacking Graphic Novels: 8 Ways to Teach Higher-Level Thinking with Comics and Visual Storytelling (Amazon | Bookshop.org). If you’re ready to really dig into this process, the book will tell you everything you need to know!

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Wow – I did a end of the year project on how to draw cartoon characters… and over the summer, thought how could this help with character development….

Somehow, your articles nearly always lead me somewhere just a little bit farther in my teaching.

I will be reading this several times. I want to get it figured out.

Thank you for reading, Monica! I’m excited to hear you will be using the post as a reference when you teach cartooning or graphic novels in your classroom. I hope you reach out if questions arise and to share your experience.

I will use this for sure.

Thank you so much for this! We do something very similar to this in my middle school and there are many helpful helpful pieces that I can share with the team to add to our graphic novel event and curriculum. I appreciate the hard work!

Thanks, Sarah! It would be interesting to see what you and your colleagues come up with and some of the student-created graphic novels, too.

Shveta .. thank you for sharing your amazing idea.

Tim

Inspirational and revealing. Thanks a lot, Shveta!!

This is a great post. I was actually considering teaching Persepolis this year, and I love this student graphic novel unit. I even just purchased Eisner’s book to get started. I’m wondering you have any of your materials available for Persepolis, perhaps on TpT or elsewhere?

Crystal, that is great news that you will teach Persepolis this year! I am working on putting together more resources. You can subscribe to my website to get emails when I add new stuff: https://shvetamiller.com

For now, I hope the YouTube video I included in the post – a model close reading of Persepolis – will be helpful. Feel free to contact me (Twitter, FB, or through my website) to suggest specific resources you think you and your students will need. Thanks for reading!

Thank you for sharing this incredible process and project. Based off of this post, one of my colleagues and I are in the process of developing a similar experience for elementary-age students. We are so excited to see how this opens up opportunities for all writers in our classroom.

That is great to hear, Alex! Feel free to reach out to me on shvetamiller.com if you have questions or are willing to share updates on your experience. I will be working on a book about teaching graphic novel creation and would love to connect with teachers who are implementing some of the ideas in my post with their students.

This was a fantastic read. I am a special education teacher to students with intellectual disabilities and this will be a great project that all students can participate in. I can’t wait to try it out.

Thanks, Krystal! Please reach out if you have questions or are willing to discuss your experience teaching graphic novels in a Special Education classroom. Shveta.Miller@gmail.com, Twitter: @ShvetaMiller

Shveta~ Thank you for your wonderful work and insights into how powerful it can be for students to write their own graphic novels. This was a fantastic podcast and loaded with great information on the website. When we return to our Florida classrooms this fall, I plan to try this unit in order to help my middle school ELA students share and process their experiences during their time at home during this pandemic.

Thanks for posting, Karen! I would love to hear about your progress with students in the Fall. If you need support, please reach out through my website: shvetamiller.com

This is such a great unit. Thank you! I wonder if you have a list of all the criteria you give out as possible goals at the beginning of the unit?

Thank you!

Hi Jasmine, The possible goals/objectives for the unit would depend on your subject area/grade level standards, what skills your students are coming into the unit with, and what objectives they will meet in other units in your class. Once you administer your diagnostic reading activity and review their KWL charts, look at the standards for your subject area/grade level to determine a variety of end goals that students can choose from. You might see that some students can already analyze visual imagery in the panels, but have not created their own panels with attention to craft and structure, so that would be an objective to include on your list. Feel free to email me for more specific guidance: shveta.miller@gmail.com

Thank you for an amazing article! Have you seen the work of Dr. Ellyn Arwood? Cartooning and flowcharting for students with Autism… its an amazing compliment to this personal graphic novel approach.

Thank you fir the recommendation to read Dr. Arwood’s work. I’ve read some research on the benefits of comics for students with ASD, but I’m looking forward to diving more into this topic.

Thanks so much for this terrific article! I’m a sixth grade special education teacher, and I’ll be team teaching reading and writing with three general education teachers this fall. I look forward to sharing this article with them and adapting your ideas to develop a graphic novel unit for our students that relates to bullying, where the students will read mentor texts and then create graphic novel memoirs of their own. Thanks again!

Thanks for sharing this, Stella! We’re so glad that the post inspired you to develop this meaningful learning experience for students.