Listen to my interview with Henry Fairfax, Mike Pardee, and Jane Shore (transcript):

Sponsored by Today by Studyo and Parlay

In almost every conversation I have with another educator—as long as we have the luxury of time to let our thoughts wander around some—we end up at a place where we start to fantasize. In talking about problems and challenges of teaching, or of school in general, one of us will say something like, “If only we had more time in the day with students,” or “Wouldn’t it be great if students could just work on big, long-term projects that really meant something to them?” or “I would love to get students out in the community, solving real problems and making a real impact.”

Usually, the fantasy dissolves after a few seconds, when the dreamer remembers the limitations placed on them by standardized tests, lockstep schedules, pacing guides, and grading expectations, a set of constraints that all fall under the umbrella of The Way We’ve Always Done Things. Most people locked in these systems have dreams of how things could get better, but they have no idea where to start.

Some teachers figure it out by building a school-within-a-school, like the three who started the Apollo School, a three-hour interdisciplinary program at a high school in York, Pennsylvania. Others do it within a single class period, like Indiana teacher Don Wettrick did with his innovation class.

Other people go even further and start from scratch, building a whole new school with the fantasy at the center, rather than forcing the fantasy to work around existing limitations. Today we’ll be looking at a school like that: Philadelphia’s Revolution School. Currently nearing the end of its second school year, this high school is the end product of a group of brave, forward-thinking educators who saw what education could be, and instead of trying to work within the system, asked themselves, “Why don’t we just build it?”

To learn more about Revolution I interviewed three people: Henry Fairfax, who is Revolution’s Head of School, Jane Shore, their Head of Research and Innovation, and Mike Pardee, one of Revolution’s Master Educators. You can listen to our whole conversation above, or stay here for an overview.

One last thing: I realize that almost everyone reading this is in a situation where they can’t necessarily replicate what this school is doing. It would be understandable if you learned about Revolution and thought, Well that sounds great, but it’s basically impossible in my district. I’m spotlighting this school because I want you to start thinking about ways you could do something kind of like this, how you might be able to reconfigure some part of your school day, collaborate with other teachers, reach out for community partnerships, or at the very least brainstorm some possibilities. This exact thing may not be doable in your school—at least maybe not in the near future. But it might take shape as an elective, a two-hour combined class, a special program within your school, or even a summer program you might launch together with a few other teachers, as Mike Pardee puts it, a group of “crazy innovative people who are willing to take such a leap.”

My hope is to get you thinking about what your leap might look like.

How Revolution School Works

The Basics

Revolution School is a private high school in Philadelphia with a current student population of 17 students. They started their first year (2019-2020) with only ninth graders, then added a new freshman class for the current school year (2020-2021). Although Revolution is its own program, they share a building with Community Partnership School, which serves students in kindergarten through 5th grade. Tuition is charged on a sliding scale based on each family’s ability to pay. The remaining funds come from grants.

Curriculum

Learning at Revolution is built around inquiry lanes, interdisciplinary study pathways that focus on big questions like these:

- What’s Driving What? How do public decisions around transportation impact access to educational and economic opportunities?

- Neighborhoods in Transition: What defines a neighborhood? How do stories give us a lens into neighborhoods? How can public artwork and public service promote community empowerment and instill pride of place?

- WaterWays: How has Philadelphia’s location at the confluence of two rivers provided both opportunity and challenge to its residents?

Each semester, students choose two interdisciplinary projects in these lanes, with one full day per week devoted to each one. These flexible blocks of time allow students to focus deeply on their work, collaborate with others, travel off-campus for research, and “learn to organize (their) time without shifting focus at predetermined intervals.”

Students spend the remaining hours in writing and math labs, reading, doing personal development work in Advisory periods, and participating in Mastery Workshops, where they work to refine their skills in specific areas, such as performance or design, alongside skilled artists and practitioners from the city of Philadelphia.

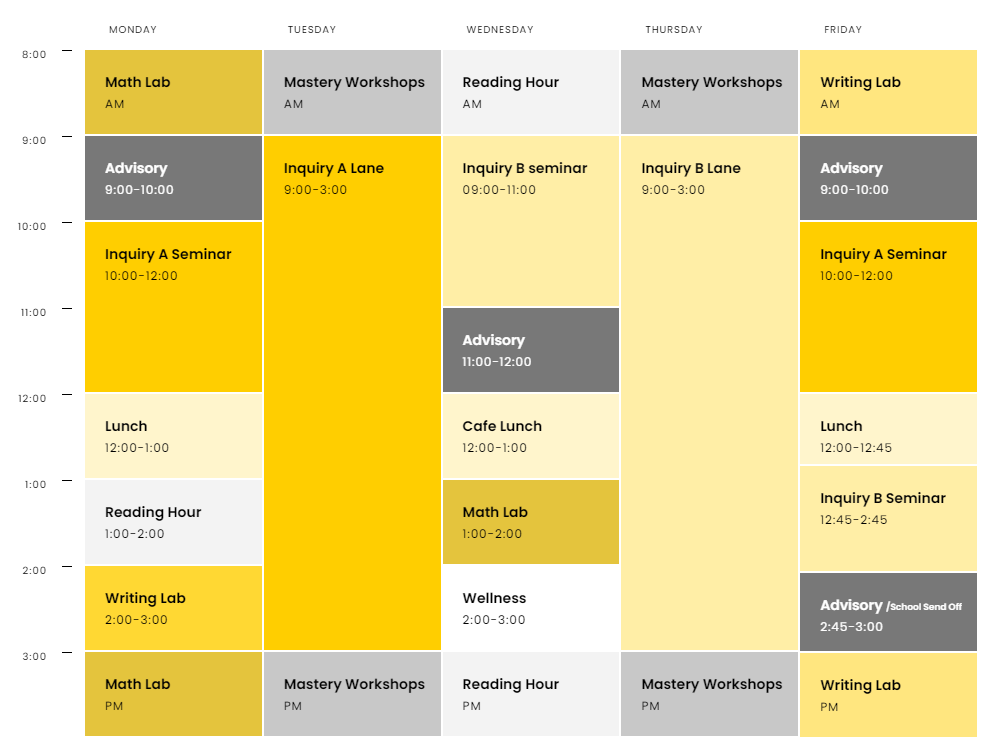

The chart below shows a typical week’s schedule at Revolution, with two large blocks of time set aside for inquiry projects (an interactive version of the chart can be found here). Note that the top and bottom row are duplicates: Students choose between an 8am-3pm schedule, or a 9am-4pm schedule.

Assessment happens through multiple pathways. Students also give end-of-semester “Presentations of Learning,” where they share what they’ve learned and support it with various artifacts as evidence. Revolution does give grades, but they don’t arrive at them in a traditional way. Here’s how they describe their approach on the website: “Our goal is not to hand out letters or gold stars, but to help you go from good to better to best. Our focus is on growth, not grades. Revolution School teachers will never use low grades to pressure you into achieving. Instead, they’ll look at your progress over time. Students who need a bit more time to gain certain skills will receive a ‘not yet,’ then work with teachers to take concrete steps toward achieving mastery in that area.”

And what about standards? Does Revolution hold itself accountable for meeting any kind of defined academic standards? Because they are a private school, they are not legally required to document this kind of alignment, but that doesn’t mean rigorous academic work isn’t happening.

“We have a slightly different approach to pedagogy and curriculum than state standards necessarily often entail,” Pardee says. “It’s a work of art to build the bridges between what was and what will be.”

Still, as they craft their vision, “We don’t want to throw out the baby with the bathwater,” Pardee says. “It matters to us that we deliver academically enriched curricular education that prepares kids for college or whatever beyond, but we want to do it in ways that leverage their passions and interests and connect with them in ways that I no longer found most conventional educational approaches doing.”

Community Partnerships

From its inception, Revolution’s founders wanted the school to be firmly embedded in the community, so they work hard to make sure community partnerships are an integral part of the learning.

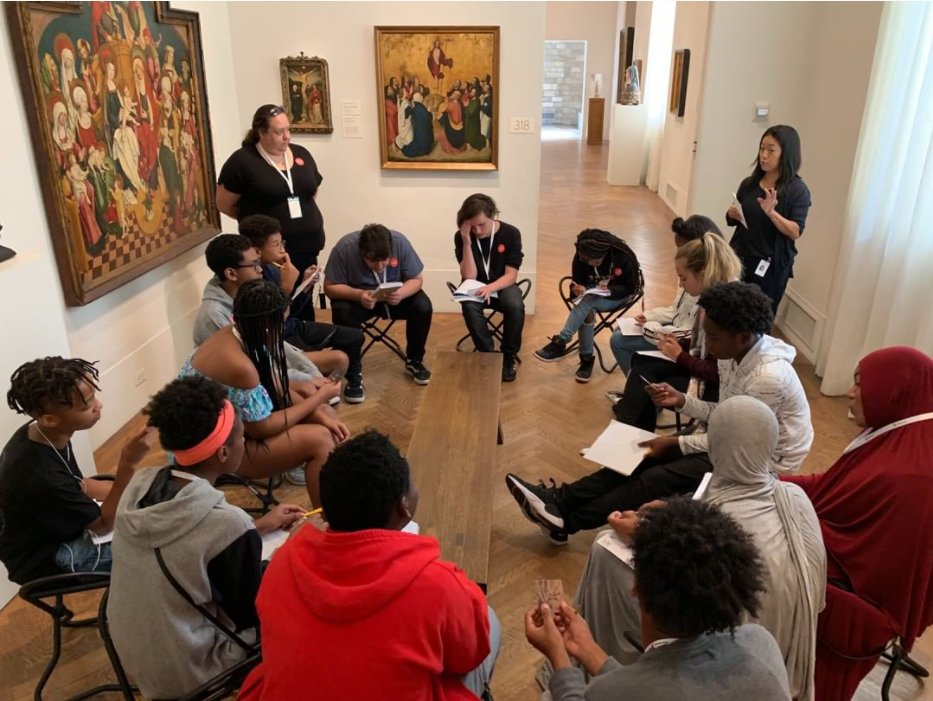

“We really see the city of Philadelphia as an extension of our classroom,” says Shore. “In the development of the school, we began to look at the assets of our city and plan around a systems thinking approach to education. So our school is all about co-creation with students and also co-creation with the community.”

The partnerships are formed with an incredibly diverse group of individuals and organizations, including journalists, small businesses, charities, media and tech companies, and artists, to name just a few. And these are real relationships: The partners get to know the students and invest time in their growth, and in return student work often enriches and improves the community.

“Our partners do more than give tours and guest lectures,” reads the partnerships page on Revolution’s website. “They sit in on student Presentations of Learning and become active mentors in our students’ lives. Some work actively alongside faculty to build out rich Project Inquiry Lanes that have real relevance in our community. Others are instrumental in our wellness program, using their expertise in food, health, and physical fitness to help our students make informed choices around personal well-being.”

School of Thought: Revolution’s Online Community

So much of the work at Revolution happens in real time and (before and after COVID) in person, so part of the school’s architecture needed to include an online space for exploring ideas and having important conversations. To meet that need, School of Thought was launched.

The weekly blog and newsletter serve as ways to gather all interested parties—from inside and outside of Philadelphia—in conversation around the work Revolution is doing.

“We see the School of Thought as an extension of the school to both fuel the school with the learning that’s taking place outside and also to fuel a learning community of people who are out there answering questions and building community around change in education,” Shore explains.

Adjusting to COVID

Revolution’s inaugural year began in September of 2019, so they only had a few months behind them before the COVID-19 pandemic hit and the world shut down in March 2020. Suddenly the school, which was created to allow maximum engagement with the community, was cut off from its most important resource.

Instead of letting this new set of circumstances crush them, Revolution regrouped, found ways to accomplish their mission through virtual means, and reframed the way they looked at the problem.

“You have to change your lens and say, okay, where are the opportunities in this moment?” Fairfax says. “One way of looking at challenges is to say ‘how are we going to get through it?’ and the other is to say ‘What opportunities can we unpack?'”

Could this work in your district?

One big reason Revolution works so well is that they were able to start from scratch, in a private setting, with a small group of students. They didn’t have to build it within an established system or push back against any existing limitations.

But that doesn’t mean you couldn’t create something similar where you are, building a program that preserves the ingredients of co-creation, community partnerships, flexible scheduling, and an emphasis on inquiry and personal development. It might not look exactly the same, but it could accomplish a lot of the same goals.

What advice do the Revolution folks have for people who want to create a similar program in their own districts?

The first piece of advice is to find like-minded people to join you. “You need a team,” Pardee says. “The trans-disciplinary and co-creating and collaborative aspects of this are built into the DNA. They’re dealbreakers if you don’t have them.”

Along with a team, you need to establish time and space to work with them. “We are in a much more labor-intensive faculty culture here,” Pardee explains. “We do a lot more planning among and between teachers than I think is typical in many schools where they just shut the door and the teacher just does his or her thing. In order to realize this vision more fully, you kind of need a more micro-schoolish approach, some collaboration and synergy and symbiosis among some group of crazy innovative people who are willing to take such a leap.”

The basic building blocks of Revolution School—inquiry-based learning, community partnerships, co-creation with students, and flexible scheduling—are available to anyone who believes in them enough to bring them to life in some form in their own district. Maybe you’re already doing something like this; if you are, please share with us in the comments and provide a link to your school or program. If this kind of thing is still in the “fantasy” stage for you, start building your team of crazy innovative people now, then come back later and tell us how it went.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

I loved listening to today’s podcast about Revolution School. I was struck by the similarities of the school’s mission and goals to my public choice school in Colorado. What a beautiful program the Revolution School is! We just completed a Progressive Education Conference in which I believe this school would have been a great addition (maybe next year!?). I will dive into their website and reach out to the school for more information. My only hope for you and your message is to continue to push the thinking of your educators and policymakers to allow for this type of program to be a regular option that is PUBLIC (not private, not charter). Our public schools need some significant overhauls. Progressive education, much like what Revolution is doing, is needed in ALL schools! Thank you for getting the word out!

Megan,

We would love to connect further! Please reach out to me a pt Jane@revolutionschool.org

Jane

thanks so much for the way you framed this with the reminder to think about what pieces we might want to incorporate even just into a single session.

it made me more aware of my own resistance as i read. the cycle of thinking ‘wow that’s amazing’ followed by the flood of reasons why it wouldn’t work for me.

i’m taking my time with this one. letting those floods wash over me, but then trying to return to understand, and ways i might sneak in some of what i learn.

I teach social studies in a public high school in Albany, NY that was designed by a tiny group of reform-minded educators who turned their wildest pedagogical fantasies into a viable program. This school, Tech Valley High School, is now in its 12th year. I loved reading about the Revolution School and echo their conclusion that you simply must build a faculty culture where teachers have time, autonomy, and space to brainstorm and plan together. Here’s what I love about our school: interdisciplinary project-based learning, students work in teams of 2-4 for every project in every class, collaboration skills are explicitly taught, we a strong advisory program, tons of community partners who support our projects in meaningful ways, authentic ways to showcase learning, a 2-4 week halt of regular classes per year so students design and implement a project of their own, breakout spaces throughout the building for student teams to work, community service requirements, a mindfulness program, in-depth parent-teacher-student meetings at least twice a year, a decentralized hierarchy with consensus decision making among staff and admin…I could go on and on. My school is outrageously awesome. I just wanted to throw it out there that this CAN be done in a public school setting (although we are an alternate program for districts, not our own big district). This kind of model CAN be viable, lasting, and successful. I love my job, I love my school and I love my colleagues. It’s definitely labor-intensive, but I’m so proud to follow in the footsteps of educators who created a space for me to teach creatively, passionately, and meaningfully. I hope the Revolution School has as much success as we have had.

As I was reading this article, I see our school, Nettleton STEAM in this amazing school. Nettleton STEAM is a project-based learning school, grades 3-6 in Jonesboro, Arkansas. In our mission statement, we describe STEAM as a school “where learning is reimagined.” We integrate the arts into all of the core subjects, have school wide projects and grade level projects with a central essential question that our students solve with the help of community leaders, and global and local partners. We have 2 Makerspaces, Clean and Messy, where students are able to follow their passions through tinkering, constructing, creating, and collaborating. We teach the 21st century skills and service learning, and a lot of our projects center around helping others and building that servant heart in our students, In our second year, we obtained Cognia STEM Certification and were the first in Arkansas and 1 of 200 in the world with this distinction. In the fall of 2020, which was our 3rd year, we hosted a NASA In-Flight Educational Downlink where our students got to ask questions live of astronauts aboard the International Space Station. President Bill Clinton recorded a video for our downlink and has plans to visit our school as soon as COVID is over. Our Arkansas governor has visited STEAM twice in 2020. In our 4th year, we are working with A-State as part of a SPOCS project where our students are the Citizen Science portion of the project. These college students will collaborate with our students to perform the same experiments in gravity as those that will be sent to the International Space Station in 2022 in microgravity. They will be looking at the degradation of plastic by using waxworms, and because the focus of the project is sustainability, we will carry out that focus as our school wide, year long project. This description is just the tip of the iceberg of what Nettleton STEAM is, but I felt compelled to share part of our story. 🙂

As someone who has worked in private and public schools, there are so many opportunties based on what Revolution shared. At our public middle school, we have been able to offer a Social Entrepreneur elective, teams are working with classrooms in other countries using the Design Thinking Process and teachers are using different structures of personalized learning. While I agree, I would love to work at Revolution, I am thankful for the progressive work that we have been able to within the public school structure.

I really enjoyed learning about Revolutions alternative schedule and community connections. It did, in fact, put me in mind of some of the ways my school has tried and is trying to do some similar things. St. Johnsbury Academy is also a private school, but we feel a lot like a public school in many ways. Two-thirds of our student body (totalling about 900) are day students who are tuitioned by their towns via Vermont’s version of school choice, and because of this, although our independence is prized, we do need to respond to many of the same constraints as public schools.

One program that I supervise is our Field Semester, where a dozen students and 3 teachers take all day together to complete projects and learning around Ecology, Natural Resource Management, Social Studies of Sustainability (how people shape and are shaped by their historically-informed landscapes), and Environmental Literature and Composition. Students in this program pursue agricultural, economic, and outdoor-recreation projects with community partners, work and learn outdoors most of the time, and once a week cook a meal together from local foods. A similar intensive course with a focus on engineering design and innovation is in the pilot stages.

Another way we have made experiences like this accessible to all students is via our Senior Capstone course. This is a full course (1 semester in our block schedule) that asks seniors to demonstrate that they have met our school-wide standards of character, community, and inquiry via an independent project entirely of their own choosing, planning, and implementing. It culminates in a conference-style public presentation of their work and process. Just to give a flavor: this semester I have one student creating a podcast exploring black history through music; another research soil contamination and collected soil samples from a nearby cemetery to analyze; a few years ago a capstone project successfully led the VT state legislature to allow 17-year olds to vote in primary elections if they would be 18 by the time of the general election. Meeting within the constraints of the school day, the class itself allows students time to pursue their work with the mentorship of a teacher-advisor, and classmates give peer feedback, coaching, and moral support along the way.

And finally, I’d be remiss to not talk up the ways that vocational centers do many of these things. Ours is somewhat special in that it is integrated into the main campus of the Academy and not a special pull-out program as it is for many districts. (It is also considered a public and state-funded tech center.) With their emphasis on authentic tasks and hands-on learning, the double-block, multiple-semester courses in subjects like auto body, woodworking, and the culinary arts offer a lot of opportunity for the things you’ve emphasized: community connections (selling food at a street fair to raise money for a non-profit), inquiry learning (design and manufacture a backlit sign for a new business downtown), co-creation with students (what does our community need that we can build?). I suspect many public districts could partner with their vocational centers in innovative ways to put these opportunities in reach of more students, and also to move past the stigma that many vo-tech programs have…those of us on the “college-prep” side can learn a lot from how the tech centers lead learning.

We’re building something very similar at San Francisco Girls’ School, but haven’t opened yet. We have an experiential learning day that’s similar to the interdisciplinary lanes of Revolution School. It’s great to see a model like this succeed. I can’t wait to launch our own version.

This was so inspiring! I have known Henry Fairfax for a number of years, and was thrilled when he decided to move forward with this dream to start the Revolution School. Their philosophy, practices, creative innovation are awe-inspiring. If I were starting again in education, THIS is where I’d want to be!

Jini Loos

Your work enhanced my knowledge and I found answers of many question that were not solved before .

thanks ,you made my day.

It was great to read and hear about the practices of Revolution school, which are similar to those in the schools from the district I work for in New York City. The group of schools for which I am deputy superintendent have actually been grouped together under one district because they are philosophically aligned in their beliefs around experiential, project-based curriculum, performance-based assessments, and student agency. What can often be difficult for schools that are trying to do this revolutionary work is that they don’t always have the support from the schools around them or their district. Having a group of schools working together to innovate around this work, particularly during this past year, has helped them to deepen their practices and better support students during in an incredibly challenging year.

This is absolutely fantastic. I’m covering a math class right now and listening to the irrelevant sh*t being taught is sending me into a funk. It’s pretty obvious how the teenagers feel about it.

Two thoughts:

1. Years ago, while on vacation, I couldn’t sleep one night. I got up and unleashed a torrent of fantasy school ideas in a note on my phone. I still have it. A lot of the ideas can’t be done with my subject, so I can’t incorporate them. But I still love reading that list. I should share it with the Revolution School people.

2. My school had a PD one day where we got into groups to brainstorm ideas for making the curriculum more relevant and innovative. A lot of brilliant ideas were floated, and the powers that be seemed to like them. The ideas never made it out of the room. Implementation takes guts, and school administrators are famously conservative in their decisions.

I found this post really inspiring! It is refreshing to hear about such a forward thinking approach to curriculum and community based learning. I have been involved with different interdisciplinary projects throughout my career including service learning, problem based learning and passion projects, but would love to be able to integrate this type of revolutionary program into the curriculum at my school. It truly exemplifies how you can enable students to develop 21st century skills while contributing to their local community. It is great to hear about how your team has responded to the challenges of the pandemic – this must have been no small feat since your program relies so heavily on working outside the school building.

I was wondering whether you are in partnership with any nearby schools in addition to local organizations and businesses?

One potential barrier to incorporating this type of program in mainstream education is the requirement to meet external curriculum criteria – do you draw on any district documents to design the content of your projects?

Another potential obstacle would be providing credentials and credits for students in post-secondary applications. Have you found that universities are amenable to your alternative transcripts, or are the AP and SAT results still a significant factor?

This was such a fabulous read. I love the way you opened the article with the reassurance that this is not meant to scare us or overwhelm us. I find myself so often thinking that I am confined by the boundaries of a curriculum and a district, and giving up on the idea of innovation and new pedagogy. As you say, we can try to “reconfigure some part of [the] school day, collaborate with other teachers, reach out for community partnerships, or at the very least brainstorm some possibilities”.

I do have one question about a potential obstacle. I currently work at a preparatory school where getting into university is a core goal for our teaching. Do you have any thoughts about how to incorporate a “Revolution” approach in a way that ensures students are credited for required classes and properly recognized by post-secondary educations?