Listen to my interview with teacher Benedict Bossut (transcript):

Until five years ago, I had no idea what Montessori was. When I heard people use the word, I assumed it was some early-childhood thing, some kind of school that was maybe a little esoteric and maybe a little privileged. Then, when my oldest child reached preschool age, and then the next kid and the next, I sent them to a Montessori preschool. During those years, I became more familiar with Maria Montessori’s philosophy, pioneered over 100 years ago in Italy, and I liked it. Still, I figured it was a preschool thing. When it was time to enroll my kids in elementary school, they went to the local public school and that was that.

For some parents, it wasn’t that simple.

Several years ago, a tiny educational revolution started in Bowling Green, Kentucky. At that time, parents of elementary-age students could choose between traditional public schools or private Christian schools. A small group of these parents found themselves wanting more. They all had children enrolled in Montessori preschools and wished their children could continue to benefit from that approach; what they wanted was to start a Montessori elementary school right in their town. Other schools like this existed in other parts of the country, but not there.

First, they held several meetings to see if enough families would be interested in the school. Once this was established, they scouted possible locations and settled on the Montessori School of Bowling Green, a primary school that was already established. It was decided that the elementary “wing” of the school, which would serve ages six through twelve, would be housed on the upper floor of the school.

The only problem was, no one in town was certified to teach with the Montessori method at the elementary level. So one of the parents, Benedicte Bossut, who had a year of experience as an assistant at a Montessori preschool, enrolled in an intensive, one-year certification program in Cleveland, Ohio. With this completed, the school opened in August of 2012 with an enrollment of 10 students.

I visited the school a few weeks ago to learn more about how the Montessori philosophy is applied at the elementary level. I was expecting to find something, well…nice. I expected it to be calm. I expected the natural wood furniture, the sparse decor, the mats on the floors. I expected to see the beads for math study, the same ones I’d seen in my kids’ preschool. Nice. Possibly lacking in academic rigor, I thought privately, but nice.

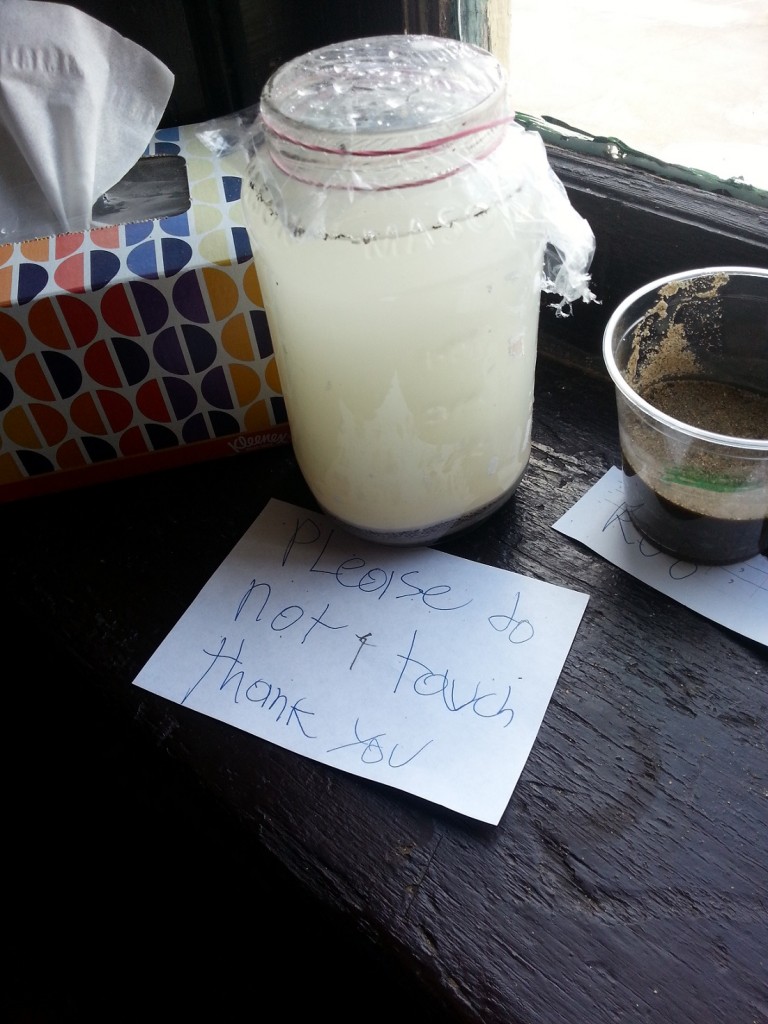

What I didn’t expect was the attitude of the students: They were focused. They were calm. They retrieved their lessons and worked at them seriously, while still maintaining a sense of humor. And their work was plenty rigorous: They researched sharks, performed multi-digit multiplication, wrote letters, studied — in great detail — the geography of Australia, New Zealand, and all of its surrounding islands (none of which I had ever heard of). As I sat watching, drinking a cup of pumpkin spice tea one student fetched for me from the kitchen, I was overwhelmed by all of it. Because I didn’t really think this kind of learning was possible in a school. I had been spending a lot of time lately following online arguments about Common Core and Race to the Top and testing and data and accountability and…none of that felt like this.

And I thought, what they have here, couldn’t we have some of this in a more traditional school? To convert all of our schools to the Montessori method would be amazing and wonderful, but that feels like too big of a dream. What about right now? Is there anything a teacher in a “regular” school could do right now to apply these principles to his or her own students?

I think we could. But I’ll get to that in a moment. First, let’s look inside the school to see how it works.

A Typical Day

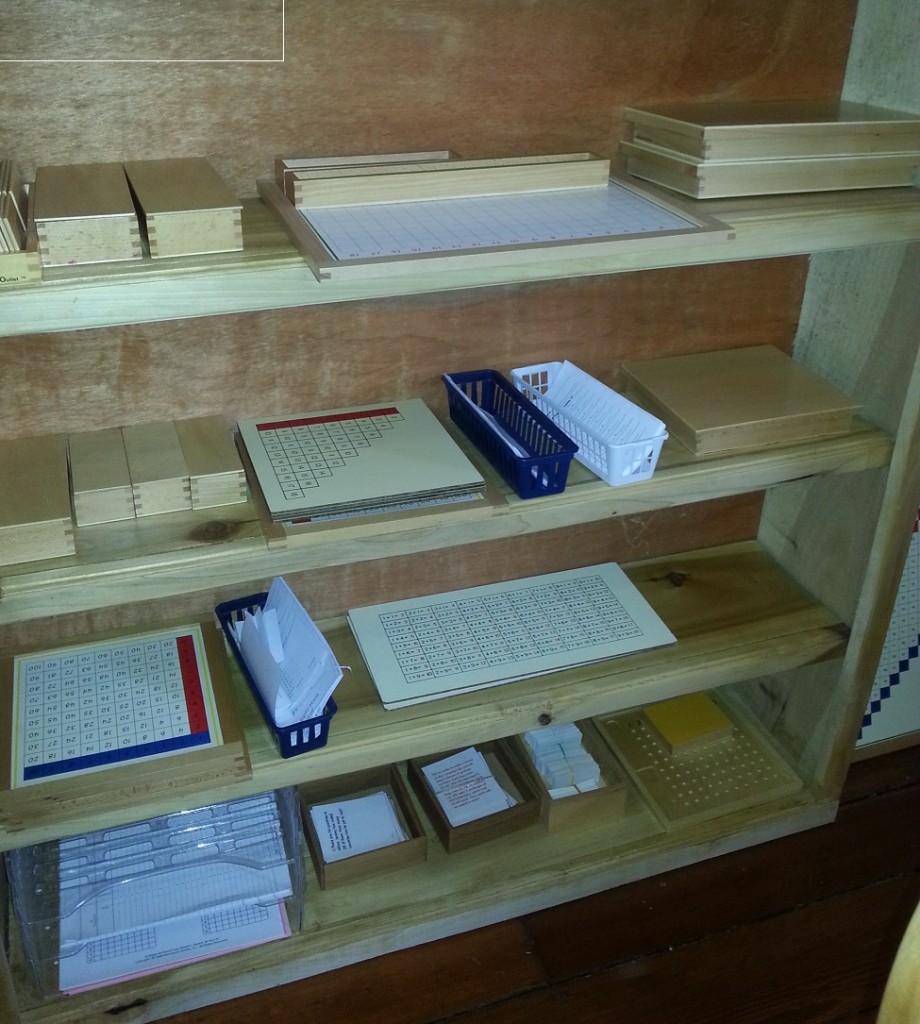

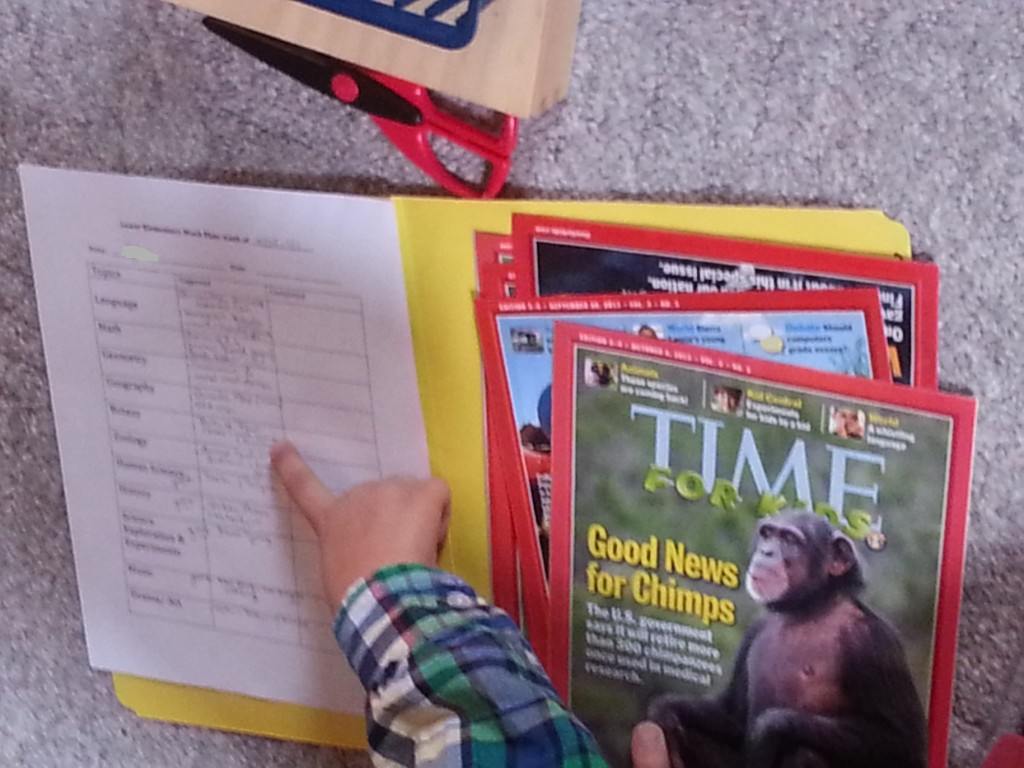

The school day begins at 7:30 a.m. As they arrive, students go to their agendas, folders maintained by “Miss Benedicte” containing a chart of suggested lessons for the week. Students choose whichever lessons they’d like to work on first, retrieve the appropriate materials for those lessons, and begin, working on whatever surface is most comfortable. For some, this means setting up their lesson on one of several tables. For others, it means rolling out a mat on the floor.

A little after 8:00, students and teachers do some tai chi or yoga, and at 8:30 they assemble on the floor for the morning group meeting, where Ms. Bossut goes over the plan for the day and students have an opportunity to share stories, thoughts or questions.

After Morning Group, students and teacher enter into a 3-hour work period. Those students who began lessons earlier in the day continue with those; others start new ones.

Around 11:45, the group gathers again to give students another opportunity to share and present what they are learning with the rest of the class. This is followed by lunch and some time outdoors, and then another 90-minute work period, which includes reading groups and other reading work. At 2:30 the students do classroom maintenance chores, which are done on a rotation. Dismissal is between 2:45 and 3:00 p.m.

The Montessori Difference

Clearly, the structure of a Montessori school day is different from what you’d find in a more traditional school. But apart from that schedule, what fundamental characteristics make Montessori schools unique?

Individual Pacing: The most noticeable difference between a traditional school and a Montessori school is that students move at their own pace. Rather than participating in a teacher-led lecture or activity, where all students perform the same tasks and are put on a path to meet the same academic goal each day, each student works on lessons that are precisely fit to their current ability level.

Moreover, they choose which lessons to do when. Although Bossut’s intention is for students to complete all the suggested lessons in the week, students do them in whatever order they like, and for as long as they like. If a student is really absorbed in a math lesson, for example, she can spend three hours on it in order to master the skill. And if a student shows a particular interest in a topic, say, the Amazon River, Bossut will work to tailor the activities in the agenda so that they incorporate more of that topic, while still meeting the curricular goals.

Mixed Age Groups: Maria Montessori believed that mixed age groups were of great benefit to students, that the role-modeling and collaboration possible in this kind of blend could enhance not just learning, but social and emotional development as well. So students from ages six to twelve all work in the same space. The older students often naturally take on leadership roles, and help set the tone for a working environment, but younger students also find ways to lead, whether through their growing knowledge in a particular subject area, a special talent, or with their own unique set of social skills.

Mixing age groups also allows for more differentiation. If students aren’t separated by age, they can more easily be paired based on readiness or interest. When a Montessori teacher needs a student to demonstrate a skill for another student, she isn’t limited to only kids in that student’s age group — she can choose the best student for the job, regardless of their age.

Flexibility: Although the school maintains a regular schedule of daily activities, they also allow for changes to accommodate special events. The morning work period may sometimes be used to welcome visitors or for “going out” lessons to the local library, field trips to local businesses, or shopping for classroom snacks and community meals, all of which are planned and served by the students themselves. This kind of flexibility is something homeschoolers also tout as a huge benefit to their kind of schooling — the ability to take advantage of opportunities as they arise, rather than being held too closely to a set schedule.

Focus on the Whole Child: Although students do academic work every day, the Montessori curriculum focuses on developing the “whole child,” emotionally, physically, socially, and academically. “When people look at an academic program, they specifically look at academics. But Montessori is in the philosophy that academic is insufficient to the whole child,” Ms. Bossut explains. “It’s independence, it’s capacity for concentration. It’s capacity for sharing space. It’s respect for the community.”

This philosophy is apparent in the way students are treated. If a child is getting distracted or is having trouble focusing, Bossut does not reprimand him. Instead, she tries to re-ignite his interest, determine what is confusing him, or help him find another task that’s more appealing. Students are also given plenty of responsibility for maintaining the classroom, planning meals and snacks, and working through problems as they come up. All of these are not seen as distractions from the curriculum, but important parts of the curriculum itself.

The Take-Away

What, if anything, can teachers in traditional schools do to incorporate some of the Montessori philosophy in their own classrooms? Although some may argue that this approach is an all-or-nothing thing, and certainly the environment in a purely Montessori classroom is optimal for student learning, I think there are small steps we can take.

The first step might be creating centers students can use themselves with little or no help to develop skills or explore interests. This sounds like a massive project, but it’s possible to start small and simple. Materials related to the current unit under study can be brought in and made available to students. Or even unrelated — find out what your students are interested in and point them toward materials that will help them explore these interests. In traditional school settings, we are used to chopping up and dividing content areas, but if a student has already met the goals we’ve set for a certain content area, why not let them explore an entirely different subject?

Something else to consider would be setting weekly goals, rather than trying to plan our classroom tasks on a day-by-day basis. Three or four goals may be the same for all students, but other goals can be set — or suggested — for individuals. Too many students to manage this? Help students learn to set their own. Again, consider allowing students to explore areas that are not strictly related to your content area (or, in an elementary classroom, to the content area designated for that time period).

The key to both of these changes working is to provide time for discussion, modeling, practice, and feedback on how to create an environment that is conducive to independent learning. This will not come right away, so it will require patience, but we can try to view these discussions and lessons as part of developing our students’ whole character, rather than a diversion from academics. And the content will likely sink in more effectively after this environment has been established: Any step we take toward developing students’ capacity to learn on their own will ultimately lead to them learning more, not less.

Finally, we might start to approach student misbehavior differently. Instead of treating student resistance or off-task behavior as defiance or disrespect, we could treat it as a symptom. In my interview with Benedicte Bossut, she told me she simply does not have discipline problems. Students who get frustrated with their work are offered another activity or advised to take a short break. If a student has trouble staying on task, Bossut interprets this as a sign she needs to work harder to ignite his interest in the lesson.

After visiting the school, I have become a huge fan of the Montessori method. We may not be ready to convert every school to this method, but it’s definitely worth considering. It has certainly outlasted every other teaching approach out there. And the way things are going lately, it might be time to look for a whole new way of doing things. Even if that “new” way is actually kind of a classic. ♦

To learn more about the Montessori School of Bowling Green, visit their website.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Both my sons attended an elementary school in Santa Barbara, CA known as “Poor Man’s Montessori.” My oldest is gifted, my youngest, also quite bright, is quite challenged by dyslexia. It worked for both of them. I would like to add to this article that this magical method of allowing kids to move at their own pace can really work social miracles. There was no bullying at our sons’ school, kids all felt like one giant family. My youngest son, great at fixing things, fixed everything mechanical in the classroom for his teacher, who cried big tears when he graduated- they were that close. My oldest, reserved and wickedly funny, was not teased for being super bright and out-of-the-box, he was looked up to by his peers for being clever. Montessori is a brave new kind of classroom that celebrates kids for being kids in a very special, and actually, quite old fashioned way. It’s peaceful, respectful, and it works!

I totally agree. There’s a lot that can be taken from Montessori into mainstream teaching.

I live in Broward County in South Florida, the 6th largest school district in the country. Our district has three public Montessori schools including one middle school: Beachside Montessori Village, Virginia Schulman Young (magnet), and Sunrise Middle.

I’ve spent a lot of time at local elementary school in the last two years which is a 100% free or reduced lunch time population yet which is managing to be a high performing high morale school. The principal by the way, just won Principal of the Year for Broward County. Angela Brown of Dillard Elementary School. When I tour her classrooms, I’m struck my how Montessori-ish it is. Students are focused. They work in small groups or alone. On the ground or at desks. Very little “teacher talk.” And while there is noise, it’s the noise of students at work.

Here’s some more info, albeit partial, on her approach:

http://educationaboutedu.blogspot.com/2015/04/dillard-elementary-school.html

I use the readers/writers workshop model in my grade 8 ELA classroom. I have been moving my students towards this sort of model all year, guiding them towards more independent self-directed learning. I agree that it helps with discipline and allows students to produce their own best work. It allows for differentiation without making students feeling like they are “different”. Everyone is different. Most days, after a 10 minute mini-lesson, students have the choice to work on their writing (topics of their choice) or to read. I have certain things I have to cover in the curriculum, so often their writing topics will follow the model presented in the mini-lesson, but they always have choice. I am really seeing the fruits of our labour as the school year begins to wind down. I think it’s a much more humane approach to learning. Thanks for sharing your experience at the Montessori school. It just proves to me that I’m on the right track.

Thank you for this article. I am looking for more information on how to integrate montessori into the public school classroom, particularly kindergarten. Do you have any additional resources?

I think Pinterest may be your best bet. Take a look at these boards for starters:

https://www.pinterest.com/debchitwood/montessori-inspired-activities-and-ideas/

https://www.pinterest.com/debchitwood/living-montessori-now-posts/

http://amshq.org/School-Resources/Public

I hope this article helps, Michelle!

Investigate the Milwaukee Public School System. They have many, many public Montessori schools and a scientific measurement of the outcomes came out of a study of this school system. They have 8 or nine public elementary schools and even middle schools. Maybe high school by now.

Hi Jennifer! I substitute teach elementary school here in Scotland, and Montessori is my favorite pedagogical system for sure – I went to a Montessori preschool in New Hampshire, Auburn Children’s House when I was little and when I returned as a grownup teaching student I found it to be the best classroom atmosphere by far of any class I had ever seen, at any age. When I had my own first grade class for a year at a traditional public school here in Glasgow, I found that a lot of Montessori technique was easy to import “under the radar” so to speak – the workspace mats were my favorite thing, but also I used Jane Nelson’s “Positive Discipline” system to try and subvert the school’s punishment-based system in my own classroom, and found that it follows Montessori philosophy closely. I also found that with a little work, I could make a variety of language and mathematics resources that students could choose to work with, and that helped them learn to work independently. There are some good online resources for making your own Montessori materials.

Beth, I substitute teach in Florida and am hoping to become a certified classroom teacher. I appreciate the suggestions of Jane Nelson’s books to help with classroom management. I also thought of going to Montessori training because the system makes so much sense to me, but I’m having a hard time justifying the expense.

Thank you, Jennifer! I’ve been following your blog for months and I just now came across this post via Angela Watson’s 40HTW club. I’m a new teacher this year (I went back to school at age 40 and just graduated – yay!) and my children both attend our local, wonderful Montessori school. They started in the public system, but just weren’t getting what they needed. Now, entering grade 5 and grade 10 (yes, our school goes all the way through high school, the only one in Canada!), they are well-balanced, curious, thoughtful, respectful and respected individuals who thrive in the self-paced, independent study environment. As a new teacher myself now (in the public system), I am challenged with how to incorporate into my new classroom some of what I have witnessed and experienced in the Montessori classrooms. I love the ideas that you have shared that can help me to at least try to pull in a few ideas. Keep up the great blog! I love your stuff! Always the right length (not to long), always helpful!

I have been a Montessori advocate for almost 30 years.

Your article warms my heart (and helps me to feel that the work and sacrifice has all been worth it).

This is awesome! i will like to join your mailing list.

Hi! I’m one of the Customer Experience Managers with Cult of Pedagogy. We’d love for you to join us. Click here to find out more.

I like the idea of centers, weekly goals, independent learning, but am skeptical of the idea of the approach to misbehavior. It might work for younger kids, but as we grow older sometimes we just have to buckle down and do things that we don’t want to do. Of course, it would be helpful to frame the task in a positive way, but the bills wouldn’t get paid (literally) if I decided that I would rather spend my time doing something else, and it would certainly take a talented teacher to ignite my interest in compiling documents for filing my taxes.

The problem with the punishments you use in your classroom is that they are fake. When you don’t pay bills, there’s a late fee, a penalty. It is fair. If your students are given opportunities for real life work, like engaging with the community through internships and making commitments to the community, they letting down their community or losing an internship would be the punishment. But so long as they live in the artificial world that is your classroom, there isn’t much to learn from your punishments other than how to please you.

It’s not about doing just what we want to do; it’s about realizing that we as adults have agency over our own lives, we’ve managed to strip that of our children. You get to pay your bills at a time you set, in a way you decide: by check, online, phone call, in the morning, during lunch, or after dinner. You control your calendar. Your students need the same, and you’ll find you don’t need to come up with fake punishment. You’ll have very adult and mature conversations and you’ll both grow.

The essential idea within a Montessori classroom are freedom within limits and natural consequences. In an elementary environment, children are indeed free to choose what they work on and when they work on something, as well whether they want to collaborate or work independently. The limit is their work journal. children keep a work journal to track their time (beginning and ending time of each lesson) and their work. This helps them with developing time and project management skill and be accountable. If, say,they don’t complete work, they can’t just choose to do something else.

I am very intrigued with the Montessori classroom. I find myself giving students more choice and freedom the longer I teach. By giving student agency they feel a stronger sense of ownership which in turn results in deeper understandings with less struggle. As I learn more about the Montessori program, I can see the strong links to the Humanistic philosophy of education where students are part of the planning and content is adjusted to the student’s strengths and skills. This learner-centered focus places the teacher as a guide rather than an oracle. I also enjoy the collaborative aspect of the Montessori program. By creating a collaborative classroom, I find students are more eager to learn if they can connect with their peers. These “progressive” ideas are in actuality what we ask adults to do daily. With that in mind, I think it is essential that we teach students how to navigate this type of learning.

i have really been educated with all that i have read so far.The only challenge i have where i presently work is that i am just the only person knowledgeable in the Montessori method in my little way.but i truly want to learn more. Secondly,my first son is intelligent,but too playful.This has really affected his performance bringing him from A grade to B grade,which makes me feel so so sad.Coming across SETH PERLER’s post on Executive Function blew my mind.will ask for more.thank you Angela.

A huge disservice was done to our world when we separated learning from play. What is learning if not playing with new and old ideas?

In my work as a New Tech Network educator, I got to visit Towles Intermediate School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Towles is Montessori for grades 1-6 and PBL for grades 7 and 8. Students transition very easily from Montessori to a PBL classroom because the two models share an emphasis on sustained inquiry and are student centered. I loved visiting the school and seeing first graders super focused on independent work!

Thank you for sharing Jennifer! I am a graduate student doing research about the esoteric Montessori divide you speak of and how we can create bridges between the private and public sector to make it more accessible to all populations. It is clear you are both a parent and an advocate for the Montessori method in the public sector. It was helpful to read about your perspective.

I like how you mentioned that Montessori schools have kids that study at their own pace which is completely different than more traditional structured education. Kids do work best at their own pace because each one is different in coping with the information they receive. If I get to ever have kids, I’ll make sure they study at a Montessori school so they can receive the best educational methods possible. Thank you.

While I totally agree with the ability of the Montessori system and that it can work in our US school systems. I also believe I need to explore how I could adapt my preschool more on these ideas. Finding my own way to adjust my current environments to help my little students that are under 5.

I’m interested in this topic for my upper level French classes. I am baffled as to where I should start. Any resources??

Erica,

The Montessori Method is really about independent and self-directed learning that’s inquiry-based, because of that, I think there’s a lot you can do.

To start, here’s a link to the American Montessori Society that provides answers about Montessori:

–FAQ about Montessori. Pull out what is most applicable to you.

Also, here are some teaching strategies that may be a good place to start:

–Chat Stations

–Deeper Class Discussions with the TQE Method

–Big List of Classroom Discussion Strategies

I’m thinking that you could take any of the strategies listed above and apply them to your upper-level French classes. You’ll find that the strategies above shift the focus in the classroom from being teacher-directed to more student-directed.

I hope this helps!

Montessori classrooms are really helpful for kids to build their basic knowledge. Thank you so much for sharing so much information about Montessori classrooms.

Hello-I am a Primary Montessori teacher in Milwaukee Public Schools. I always love to hear the praises of the children in our schools! However, I would caution against “adopting” Montessori elements into traditional classrooms. Children who grow up in Montessori from early ages have a foundation in independent learning – or what we call auto-education. We have seen children transfer into Montessori at elementary and seeming to fall off a cliff, overwhelmed with choices and no guardrails. I like that Jennifer recommends going slow, and being patient. I would double down on that advice, as well as to warn that children who grow up in educational systems with a teacher-centered , highly-controlled environment might not like a lot of choices, or independent learning. So, proceed with caution, and check in a lot with the students, please!

I like how you said that the children at a Montessori preschool were calm and focused. I want my kids to have self-control like that. I’ll look for a Montessori school near us.

My son was lucky enough to attend one of the very few public Montessori Jr/Sr High Schools in the US. It is intentionally located in Denver’s inner city and facilitates the kids’ engagement in the community. We were happy to find a school that promised not to focus on preparing kids for standardized tests and use hands-on experiences for learning — designing and building a chicken coop for science & math. Upon graduation, my son was extremely prepared for his college experience. At Denver Montessori Jr/Sr High, he learned how to manage his time well, take control of his learning, and develop real friendships. Thank you DMHS!

I taught music at a Montessori school for 7 years. When I first walked in, I thought, “This looks normal!.” The standard rows of desks in most schools look artificial and arbitrary to me.

Today, studies keep coming out which show certain teaching methods work better than others – and the ones which work better were discovered by Maria Montessori decades ago. Mainstream education inches toward the Montessori method, all the while criticizing it. It is criticized, I think, because the critics have not seen a real Montessori classroom. The Montessori name / method are not trademarked, so anyone may claim they are “Montessori” without actually following the Method. This often results in a “Montesorta” classroom, doing “sorta” Montessori, but not really.