Dear Cult of Pedagogy,

I just finished my first year of teaching at the college level. I’m embarrassed to say it, but I had a lot of behavior problems. In almost every class I had a few students who would talk or text right over my lecture. I never expected to have these issues in college, but I do, and I don’t know what to do about it. Do you know of any resources that can help me deal with this issue?

I feel you, friend. I taught at the college level for four years, and though most of my classes went well, I did have some students whose behavior made me think, Seriously? You’re in college? Coming from a middle school environment, I expected behavior to be a non-issue at the college level, so going in, I didn’t even think to address behavior in my course syllabus. That was a mistake: Many college students still need lots of guidance about appropriate and respectful behavior in the classroom.

Quick Fixes for Classroom Disruption

First off, I’d advise you to use proximity. If you stay at the front of the room the whole time, students know they can pursue other activities without you noticing. If possible, move around the room as you conduct class, standing close to students who are talking or texting—the closer you get, the less likely they are to continue that behavior.

Secondly, nip minor disruptions in the bud without getting into a big power struggle. One way to do this is to ask the student who is engaging in off-task behavior a content-based question to get her engaged in the lesson. This approach is explained in my video, Distract the Distractor.

Avoid sarcasm. Although many teachers believe this projects confidence, it actually looks more like weakness and in most cases, makes students lose respect for you. It can also be unclear: If a student is texting his buddy, a snarky comment like, “John, tell your girlfriend hi from us” will just be confusing. Along those same lines, avoid publicly embarrassing students. Although it might work in the short term to get students back on track, it does nothing to build the kind of respectful relationship you should want with your students. Instead, address the behavior directly. In an even tone, say something simple like, “Please put your phone away,” or “Your conversation is distracting the class. Please save it for later.”

Finally, talking privately with the disruptive students can make a big difference. Again, in an even tone, describe the behavior you’re noticing, explain why it is a problem, and tell the student you’d like them to stop. In many cases, this is all that’s needed to change behavior.

Long-Term Solutions

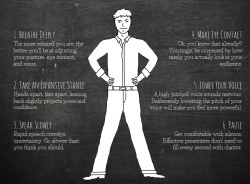

Get a (good) mentor. You can learn a lot by watching someone who has already mastered this problem. Ask a few colleagues if you can sit in on their classes to observe. John H. Shrawder, Executive Director at Teaching for Success, suggests that you also invite this person to visit your class. “Ask them to observe and perhaps video teacher-student interactions. Then, together analyze the video for unintended messages of ‘I don’t really feel in charge.’ Unconscious speech habits such as raising the tone of one’s voice at the end of each sentence weakens the person’s personal power considerably, as does a nervous laugh, speaking too softly, or not looking students in the eye.”

Vary your teaching methods. If your class is mostly lecture, your students will find other ways to entertain themselves. One very simple way to break up a lecture is think-pair-share: have students pair up to discuss a question, then call on pairs to share their response with the rest of the class. A few other easy methods you might want to try are Chat Stations, Reciprocal Learning, and Crumple and Shoot, an easy review game my college students loved.

Vary your teaching methods. If your class is mostly lecture, your students will find other ways to entertain themselves. One very simple way to break up a lecture is think-pair-share: have students pair up to discuss a question, then call on pairs to share their response with the rest of the class. A few other easy methods you might want to try are Chat Stations, Reciprocal Learning, and Crumple and Shoot, an easy review game my college students loved.

Develop class rules with students. Dave Spear, a professor at Niagara College in Ontario, Canada, regularly invites students to help him develop a behavior policy. “With a new group we spend time on the first day producing a ‘class rules’ document. I ask students what they think the rules for conduct in the classroom should be, and they do a very thorough job. If something you feel is important is missed, then bring it up and ask their opinion; for example, ‘What should be the policy on cell phone use?’ They are always more willing to follow the rules they created as opposed to the ones they have forced upon them.”

Record positive and negative behaviors. An approach that worked well for me was to maintain a notebook of student behavior. My students often needed letters of recommendation or my approval for entry into a particular academic program. Much of these were based on non-academic qualities such as punctuality, thoroughness, and ethical behavior. So I told them at the beginning of the semester that I would be recording times when they demonstrated these behaviors — or lack thereof. If a student fell asleep in class, I would simply note that, along with the date. If it never happened again, it was an isolated incident. If it happened three more times, then we had a pattern of behavior that would influence my recommendations later on. The same was true for positive behaviors: Being the first student to participate in an online discussion was noted, as were times when a student emailed me ahead of time to let me know they were going to be late to class. Your opinion of your students is formed over time, based on choices students make. Keeping a record just makes it easier to justify that opinion. I describe this process more in another post, Notebooks for Classroom Management, Part 2.

Resources for Developing a System that Works for You

If you have time to dig more deeply into your system for dealing with unwanted class behavior, these resources will help you take a more comprehensive approach:

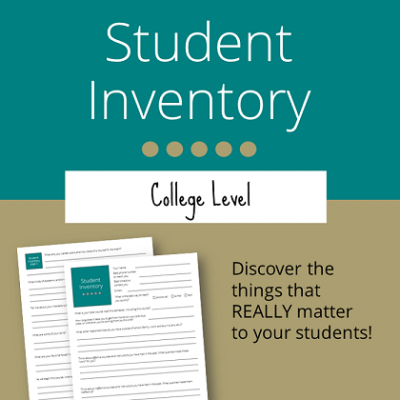

Getting to know your students is essential for preventing all kinds of discipline problems. This 2-page Student Inventory, available from my Teachers Pay Teachers store, helps you gather information about students’ work and family responsibilities, outside interests, career plans, transportation issues, and their professional and academic background. In my experience, students really appreciate being asked about these things, and building relationships with them has helped me maintain a positive classroom environment.

[Note: The links below are Amazon Affiliate links. If you click these and make a purchase from Amazon, we will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for your support!]

To get to the root of why students respond to certain teachers more positively than others, take a look at Transparent Teaching of Adolescents: Defining the Ideal Class for Students and Teachers. Mindy Keller-Kyriakides, facilitator/developer in online professional development, wrote this book in collaboration with her own former students. In the book, she explores ways to build rapport and instill mutual trust with students. The book “was written for secondary teachers, but many of the approaches reflect andragogical principles which work well with adults, too,” says Keller-Kyriakides.

Finally, if you’re looking for a practical guide to getting it all set up — from writing a course syllabus to what to do on the last day of class, On Course: A Week-by-Week Guide to Your First Semester of College Teaching is among the most highly rated books on college teaching out there. One reviewer put it this way: “I had already read 3 books on how to teach college courses, and looked at two others. Now I wish I had started with this.” If you’re one of the many college instructors who has received little to no training in the logistics of your job, this will answer all the questions you’re too embarrassed to ask. ♦

Do you have a question about teaching, school administration, or any other kind of learning situation? Are you stuck at an educational crossroads? Are you a parent or student with a pressing question about why we do the things we do? Send me your question via my contact form and I may use it in a future post!

This site is full of stuff like this. Just try me: Sign up for my email list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration delivered right to your inbox. I know you’re busy, so I keep them short and useful every time. To thank you, I’ll send you a free copy of my e-book, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half.

I guess I just don’t get this. These are adults. If they were in a work environment and I was their boss and they kept talking or texting after I had asked them not to while I was addressing a group meeting, they would no longer work for me. If they are in my college class and they continue to behave outside of the boundaries I have set and let them know about, they are gone. Especially in college, they do not have a RIGHT to an education. It is a privilege. I think I have gotten way too old. Why is this even a question?

Jim, I think there’s a big gray area here.

If someone has a management/teaching style that’s very assertive and confident, then your approach is an obvious answer. Also, if the behavior is clearly disruptive and disrespectful, it would be easy to simply remove a student from class. But a lot of college-level teachers have no experience with having to “discipline” other adults. It’s a lot harder than it sounds. On top of that, some of the behaviors are more subtly disruptive, making it harder to address them right away.

I also personally believe that many college students (think age 18, 19, and 20) are still basically kids and still need guidance on what appropriate adult behavior looks like; I consider addressing these behaviors constructively to be part of their curriculum. Some college-level instructors would disagree, but coming from K-12, I still felt a responsibility to teach the “whole” student.

I agree with both Jim and you. While it is possible to have the student removed from the class as Jim suggests, it is also difficult to do so with adults, way more difficult than with secondary students. I have experience teaching at the high school (my favorite level) and middle school (my least favorite level) levels as well as college. When I teach at the high school and middle school levels, I am very aware that the students are teenagers and that their behavior is expected. That makes it easier for me to address the issue. However, in college we deal with students who are adults and like you said, some behavioral issues are very subtle and difficult to address. That makes the experience more frustrating. This semester I teach a course in college in which 90% of the students are dual enrollment high school students and to my amazement they have a much better behavior and attitude than actual college students in some of my sections who are in their sophomore year.

I am teaching at a relatively new college level school. New schools especially have this problem. We are trying to build a community of scholars but weaker, non-scholastic learners are entering the school. Every college I have worked at has been tolerant until they become accredited. I am struggling with bad behaviors too and these informational pages provide me ideas to work with these students.

PTandasetti

Jim – I hear you when you say “they are adults”; however, I think about: 1) while someone may be a legal adult at 18, we know that the brain has not matured until mid-20s; 2) style of the educator can impact behavior – I know of plenty situations, particularly for students of color where microaggressions happen in the classroom; or, faculty struggle with their own ability to manage a class/”hold” the space for learning; 3) not everyone has been “taught” effective ways to question/think critically/dissent – These are excuses in as much some perspectives that may be in play. One faculty style might be “do as I say – i’m in charge”; another might be “here are my expectations for this classroom; what expectations do you have”…

You are so right in what you just said about education is a privilege. When I was in college, I never disrespected my Professors nor Instructors because I was attending to get my education not to disrespect my teachers. I teach at a proprietary school and there are all types of personalities. I tell my students to think of this as a job and your grade is your paycheck.

What would be your advice for students who do not have the time to educate their professors on this issue? Is asking a peer to stop gossiping in class a counterproductive measure?

Hey Don. It sounds like you’re frustrated with the behavior of some of your classmates. Yes? I wish I had an answer. Trying to redirect our peers in their behavior is pretty tricky. I would move myself away from disruptive students, or speak to the professor about how some of your classmates’ behavior bothers you. Depending on the relationship you have with the instructor, you might try sending them a link to this post?

Hello, Jennifer. I acknowledge that confronting my peers can be dicey, but I am a trickster myself so I know my way around the proverbial tricky block. While I agree that teachers and professors need to empower themselves to stand up in the name of respect and common decency, I would point out that students should also start lifting themselves up. Relying only on the teachers to police classrooms is not a long-term solution in my eyes. If society as a whole starts to rely on boardrooms and committees exclusively to solve problems, then humans will lose the ability to stand up for themselves altogether.

I do admire your shameless plug at the end of your comment, this problem seems almost taboo.

These are great suggestions. One technique I found helpful with 17-25 year old students was to use the name of the disruptive students when giving hypothetical examples, like “Let’s say Jane was married to John and they wanted to apply for …..”

Great post! Thanks

These are good, safe, GENERAL tips – but the most important thing is knowing who you’re teaching. When I taught in England, it was a different culture, and kids LOVED sarcasm. Even respected it. In fact, the way I earned their respect was by “taking the mick” and playfully putting them in their place (for lack of a better term). I wouldn’t use that technique ever, but that’s the point – you have to adapt the culture/society/kids in front of you.

Excellent article and points of perspectives from the readers! Although I am in my early 40s but I hold dear to that old school philosophy of students must act appropriately regardless of age and I concur wholeheartedly with the first response to the article-Why is this even an issue?

Administrators need to do more to enhance a culture of student accountability on campus. More often than not, disruptive classroom behavior is chalked up due to the “kids being kids”; but at what point does that moniker get tossed to the wayside and young adults be held accountable for their actions.

Hi, I really like your materials here. Can you help do some training for our staff via skype or some other means?

Hi Mbursa! I work for Cult of Pedagogy, and in short, yes, Jenn does speaking engagements, every now and then through Skype, and details about that are HERE. After looking at the options, feel free to use the contact form and we can continue the conversation. Thanks!

I would love to incorporate student interest inventories but got scared off by FERPA and privacy concerns. How do you know where to draw the line?

I most appreciate the great examples of how to best deliver your training. Not becoming stagnant in your delivery, the great examples of how to effectively address the different attitudes. These will best most helpful when attempting to properly train a group of associates.

We’re so glad you found this helpful, Travis!

These “college kids” are adults. I think it’s time we start holding them responsible for their own behavior.

There are many other college students who are paying to be in the class that may be distracted by the talking and texting going on. As educators, we owe it to the students who are there to learn just as much as the students who are goofing off.

In college, we shouldn’t be hounding them for homework or coming up with cutesy, ineffective teaching methods to keep them entertained (many studies suggest that students don’t learn as well as we think they do in groups).

We aren’t paid to be entertainers at the college level. Learn or go leave and work at a gas station somewhere.

Kick them out of class the same way an employer would fire them for these same immature behaviors.

Tamara, while it’s natural to expect young people to learn independence and personal responsibility, it’s important to note that while college students are legally adults, they haven’t finished maturing in other ways. College professors, like K-12 educators, should consider the social-emotional need of their students as they teach the material in the most engaging and effective ways possible. Ultimately, college is a continuation of the educational experience, and as such they will benefit from any supports and structures we put in place. Ultimately, our goal here at Cult of Pedagogy is to help teachers build a toolbox of skills and strategies that allow them to teach more students more effectively, and the recommendations in this post are in line with that goal.