Listen to the interview with Angela Peery (transcript):

Sponsored by Today by Studyo and Scholastic Scope

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links,

Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

Are your students the readers, writers, and thinkers you want them to be? Is your school or system producing graduates who are ready to tackle the literacy demands of our world? If you’re not sure of these answers, it may be time for a literacy check-up.

As a researcher, author, and consultant for almost two decades now, I’ve been honored to work alongside teachers to create meaningful literacy instruction. In the past 18 months, I’ve observed over 1000 lessons—some in person, many virtually—taught by teachers in American classrooms from preschool to 12th grade. Through these observations, one thing has become abundantly clear to me: We need to do better if our children are to become highly literate.

And they simply must.

They must become lifelong readers, writers, inquirers, critical thinkers, and empathetic souls. Without high levels of literacy, they become prey to misinformation and economic manipulation. They may not fully understand or enact their rights and freedoms. They may not be able to communicate their ideas well. If not highly literate, they will earn lower wages and have a greater risk of being incarcerated (NCES, 1994). They also risk living a life devoid of the beauty and power of literature. There are so many reasons that literacy is perhaps the most pressing civil rights issue of our time.

I’ve worked with hundreds of schools and systems trying to create markedly more literate lives for their students in the past 18 years. And for 17 years prior to that, I was a teacher, administrator, and instructional coach. So, as a senior member of this profession, I have a long and deep view here. I’ve seen methodologies and legislation come and go—many of them so-called “game changers”—but what persists is literacy instruction eerily similar to my own schooling in the 1970’s and 1980’s. There are still numerous class periods filled with answer-the-questions and look-it-up-in-the-dictionary. Student-led discussion is practically nonexistent; teacher-talk and low-level questions fill the hours. Student-made posters with drawings in colored pencil abound. When asked what they’re drawing and why, students can’t supply key points from the content or use the appropriate, discipline-specific terminology.

We can do better. We must do better.

Esteemed educator Mike Schmoker has written about his experiences in schools quite extensively, and sadly, they mirror my own: “When I tour schools and classrooms with… administrators, we never lament the possible absence of instructional technology, personalized-learning strategies, or other popular (but largely unproven) ‘innovations.’ We do lament the omnipresence of worksheets; the startling disparities in the content taught by teachers teaching the same course in the same school building; the ubiquitous ‘cut, color, and paste’ activities that masquerade as literacy instruction… and the widespread inattentiveness…, abetted by the tradition of calling on only those who raise their hands—while the rest sit, passive and bored. We note the paucity of authentic reading and writing activities, even in courses where they should predominate.”

The past year and half, which I’ve spent supporting about a dozen school systems in several different states, has not changed my views. The COVID pandemic has given us an unprecedented opportunity to rethink instruction, but what I’m finding time and time again is that teachers have turned to methods and tasks that don’t work well but, in most cases, are easy to orchestrate. There is less writing (especially at the secondary level). There is more cutting, coloring, and pasting (mostly at the elementary level). There’s a good bit of clapping and singing beyond the preschool years. Teachers are showing a lot of YouTube videos without discussing them. There are more worksheet packets than I’ve ever seen. And, tragically, there is too much passive screen time. I see many classes where the kids might as well be back at their kitchen tables during lockdown because they’re doing the exact same kind of work—having the teacher and classmates nearby is not part of the work; it’s just a kid and a device, doing something together.

I’m not sure why this is happening, and frankly, I don’t want to spend a lot of time analyzing it. I understand that every teacher’s nerves are frayed. Educators have just experienced the most traumatic and stressful year of their careers. Perhaps it’s been difficult to hold true to what we know works. Perhaps we have lost our way a bit. That’s understandable. But we need to get back on track, and fast. We must excise ineffective practices and zero in on what works. The literacy check-up process can help us do that.

Defining Good Literacy Instruction

So what works? And how do we make sure we’re doing what works as often as possible?

A good starting point would be to look at what it means to be “literate.” My book What To Look for in Literacy is a practical improvement guide for literacy instruction. In the book, my co-author Tracey Shiel and I first discuss what it means to be a literate person in today’s world. In short, the well-prepared, highly literate high school graduate of today must be all of the following:

- A reader who chooses to read independently and who can tackle complex texts in all disciplines;

- An effective communicator who can speak and write well, share information effectively, defend one’s positions with compelling evidence, and collaborate well;

- A critical thinker—one who can analyze and synthesize, taking into account the credibility of sources;

- An inquirer who seeks information about his/her interests and who finds answers to meaningful questions; and

- A global citizen who embraces diversity and seeks cultural understanding.

Next, we turn to effective literacy instruction in general. Briefly, we focus on how units and lessons should be built, following a backward design process and the concept of the gradual release of responsibility. We also spend a great deal of time discussing the components of reading instruction, effective reading and writing instruction for all age levels, and content-area literacy.

After laying this groundwork, the book then provides approximately 90 research-based tools to monitor literacy instruction for each grade span: the early years (grades PK-2), elementary (3-5), middle school (6-8), and high school (9-12). The tools can be used by administrators, instructional/literacy coaches, and teachers—ideally in collegial fashion—to examine literacy instruction, reflect on practices, and plan for increased effectiveness. And while the tools can be used for various monitoring/accountability purposes, they are intended to fuel inquiry and innovation. They are not meant to be evaluative or punitive.

What follows is a sampling of check-up tools for three areas: environment, reading instruction, and writing instruction. Use these to get a sense for how effective your current literacy practices are. And when you’re ready to go deeper, you can explore all of the tools in What to Look for in Literacy.

Check-Up Area 1: Environment

Whole-School Environment

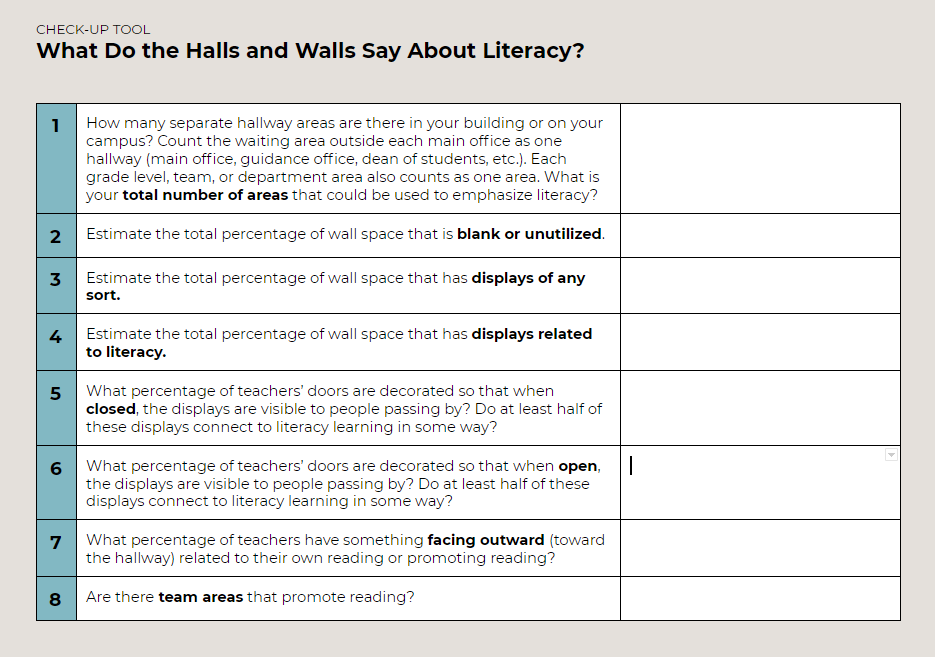

Some of the most tangible, easy-to-collect data is about the learning environment: What do the halls, walls, and materials in the school say about literacy? How do they support literacy learning?

The tool below can be used by any staff member to move around the school and look at various displays, tuning into what is supportive of literacy. It may be enlightening to take a walk throughout the school with your PLC or other team to complete this form (and take photos). “Hard” data like this often spurs conversation and change.

When using this tool to conduct literacy check-ups, I’ve found that schools often display student artwork and sports-related items (trophies, jerseys, etc.) but are missing opportunities to reinforce literacy learning. Recently, I’ve also seen a lot of displays focused on the social and emotional well-being of students, often with information about a growth mindset. Why not add student writing samples to such displays? That’s just one of many easy literacy moves that I’ve seen in some schools that have made their literacy focus more prominent.

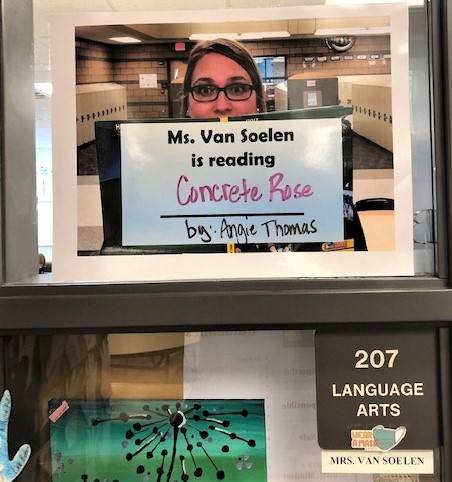

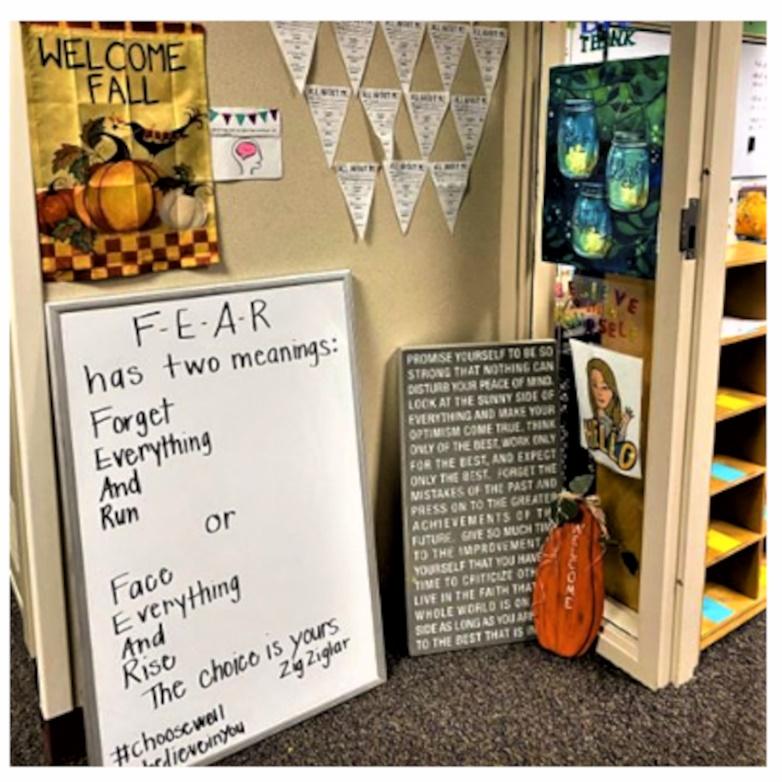

Encouraging and celebrating all things literate all throughout a school sends a clear message to students and families that literacy is valued. Displays don’t have to be elaborate or time-consuming. Look at the examples below that get the job done.

In this example, middle school teacher Melanie Van Soelen posts what she is currently reading at her door. She has shared with me that this simple display has invited several students to talk with her about the books she’s reading and to consider reading them too. A display like this shows students that teachers are lifelong readers, not just people who spend all their free time trying to create work for students. Imagine if every teacher in a school had such a display at their doors or in the front of the room! What a powerful message that sends about the importance of reading across one’s entire life.

In the next example, former third-grade teacher Leanne Brown has literacy actually spilling out of her room! She posted a motivational quote each week along with a rotating display of student writing. Simple yet powerful.

Classroom Environment

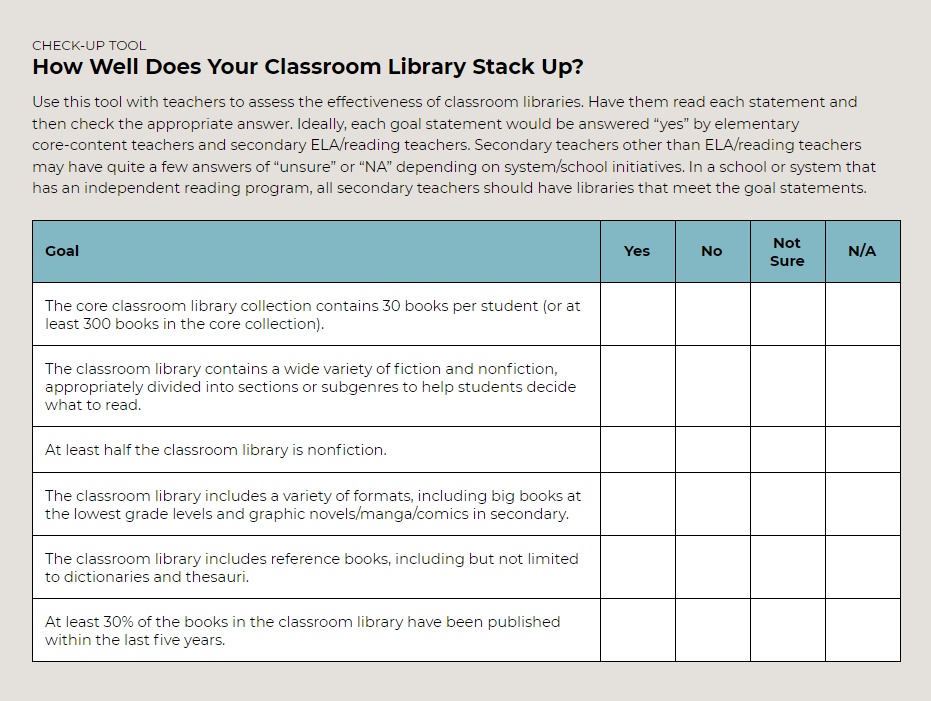

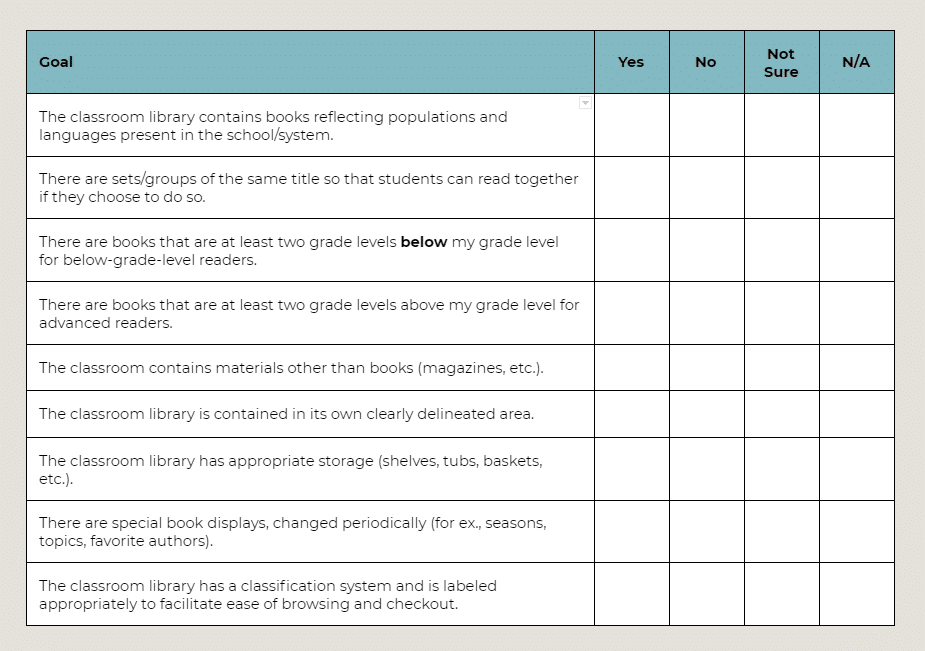

The literacy environment inside classrooms is obviously even more important, as classrooms are where students spend the majority of their time. One of the most vital parts of a literate classroom environment is a robust classroom library. As author and educator Kelly Gallagher has noted, “Rather than waiting for students to discover the joys of the library, we must bring the books to the students. Students need to be surrounded by interesting books daily, not just on those occasional days when the teacher takes them to the library.”

I am dismayed that in recent years, funding for hard-copy books has decreased. Electronic books and reading software are good resources to have, but the research is clear that students who have physical books within reach read more – they read up to 60% more in classrooms with libraries (Neuman, n.d.).

The tool below can be used to examine your own classroom library. It can also spark conversation about disparities from room to room. If we want children to be highly literate, then they must have access to materials they want to read as they go from room to room during the school day.

Check-Up Area 2: Reading Instruction

The checkup tools for instruction look a little different. They can be easily integrated into the walkthrough procedures that administrators often use. They can be used by coaches within coaching cycles, especially if a teacher is trying to improve or innovate in a specific area of literacy instruction. They can also be used by groups of teacher colleagues to collect data over time showing which instructional practices are most common (and which are nonexistent).

The three tools below would be used by an observer who watches all or part of reading instruction on any given day. You can see across the grade spans how the “look-fors” change to take into account the age levels of students and the work they are expected to do.

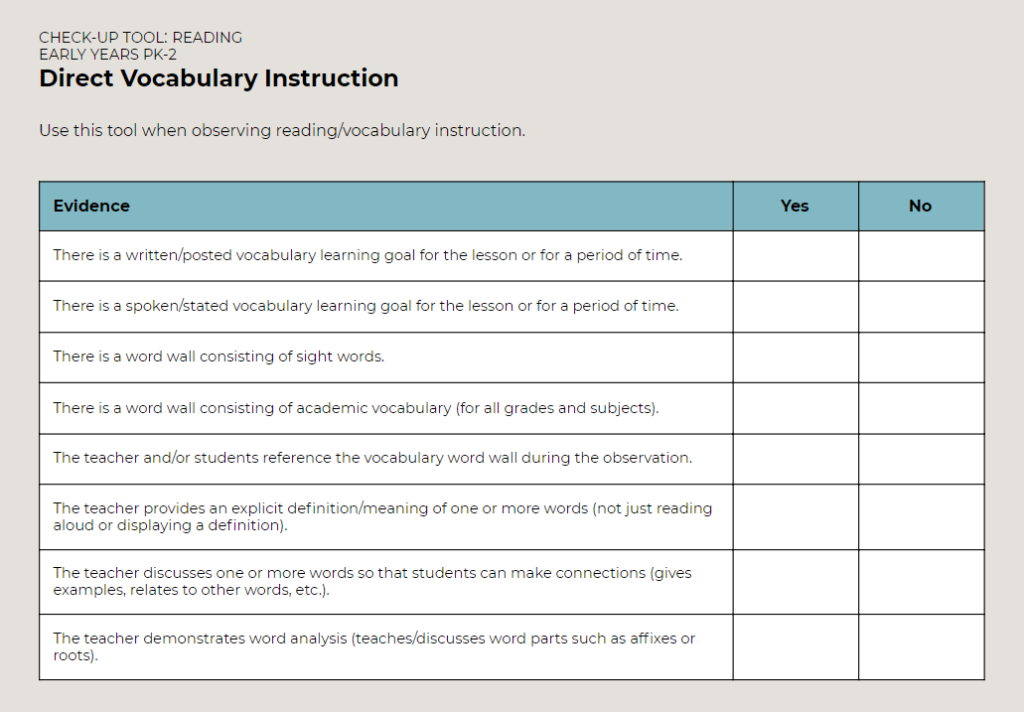

Early Years (PK-2): Direct Vocabulary Instruction

The tool below can be used to assess vocabulary instruction with our youngest students. The best early grades classrooms are awash in language, both oral and print. However, in my recent experience in early grades classrooms, there is more use of video and less oral language coming directly from the teacher. This tool examines vocabulary development with an emphasis on the teacher’s actions.

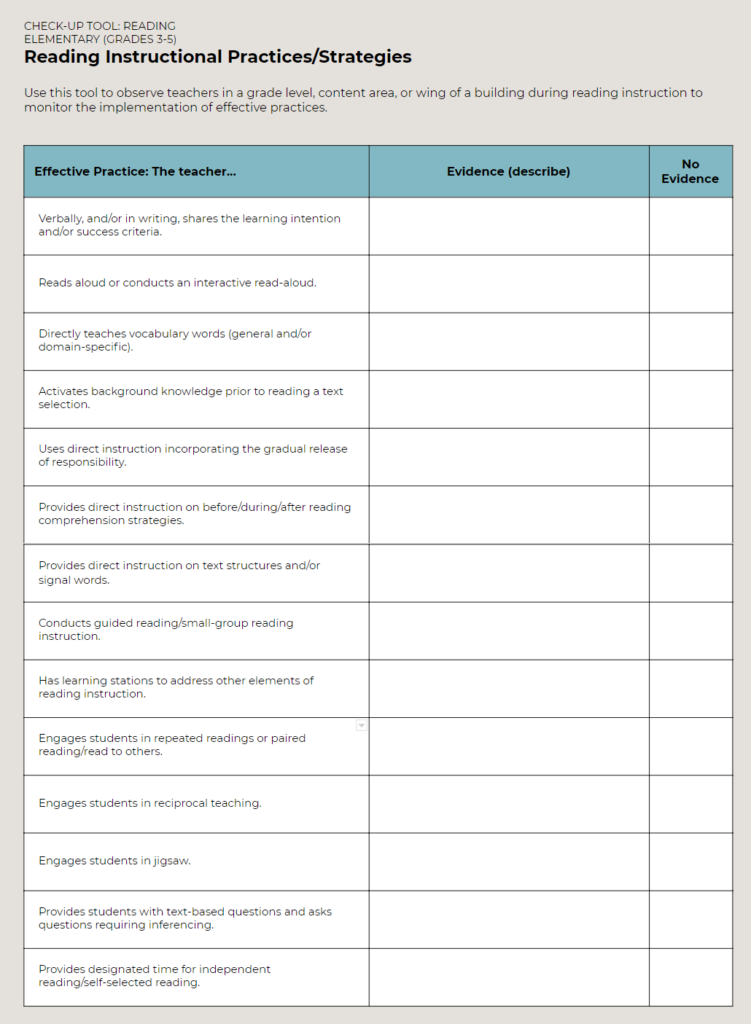

Elementary: Reading Instructional Practices/Strategies

The second tool is designed to be used when teachers are engaged in their daily literacy block. You’ll notice that the tool addresses lesson design. One of the most common things I’ve noticed since returning to face-to-face instruction in many classrooms is that lessons are not designed well for interaction. They also lack the sequence that Madeline Hunter (1982) taught us so well: getting the brain’s attention, stating an objective, providing input and modeling, and orchestrating guided practice that leads to independent practice. Reciprocal teaching and jigsaw are specific, highly effective strategies and are represented on this tool as well.

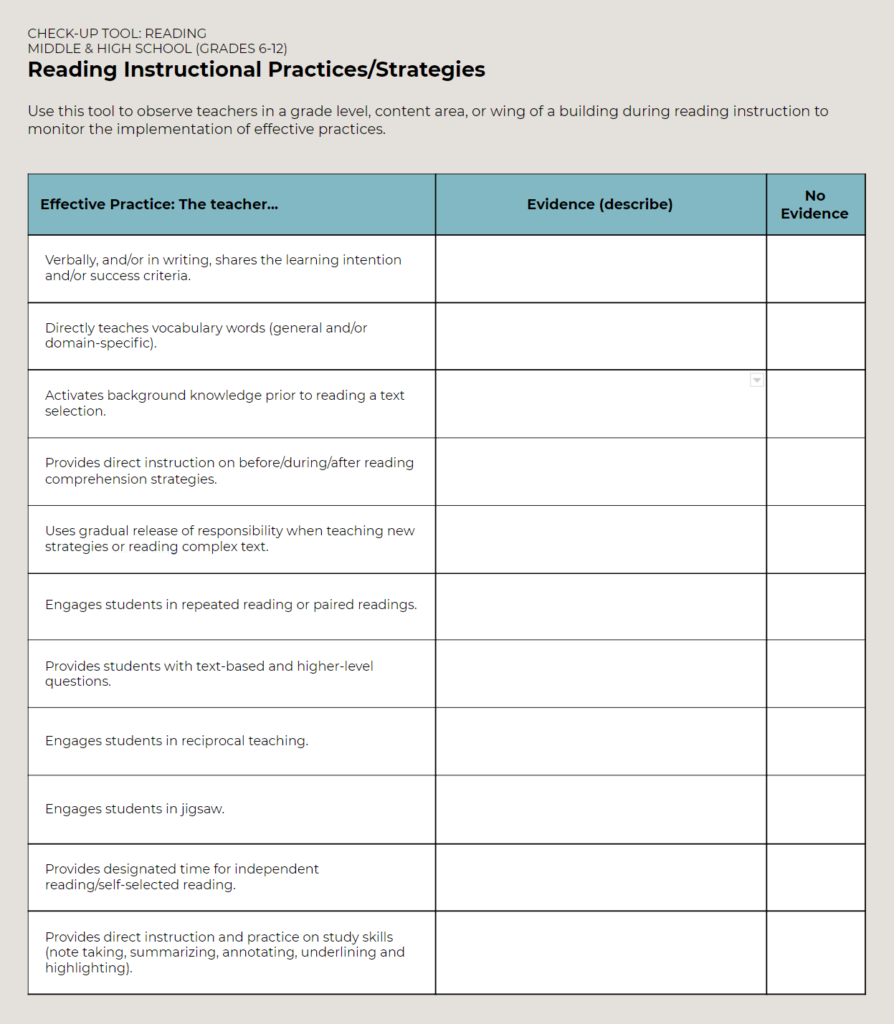

Middle/High School: Reading Instructional Practices/Strategies

The third and final tool can be used in the secondary grades when observing a teacher of any subject area and may be most useful if your school is engaged in literacy across-the-curriculum efforts. Texts at the secondary level can be very challenging for students to comprehend, and this tool delineates how text should be tackled (stating a learning intention, activating background knowledge, teaching domain-specific vocabulary). Often, in secondary classrooms, teachers simply give students the directive to read — and then are frustrated when students show no comprehension of key content and don’t know the most important terminology.

Check-Up Area 3: Writing Instruction

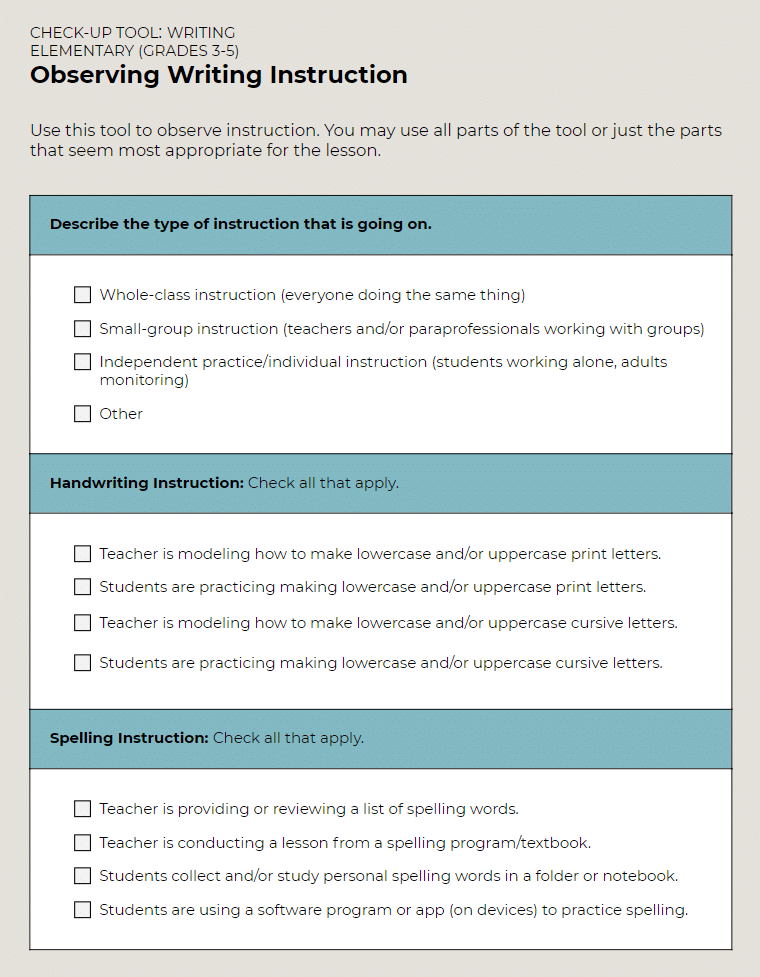

The check-up tools for writing instruction are similar to those for reading in that they reflect sound lesson and unit design and delineate specifics about effective instructional strategies. These tools can be used to collect information about the prevalent writing practices in a school or district and to help teachers reflect on their practices.

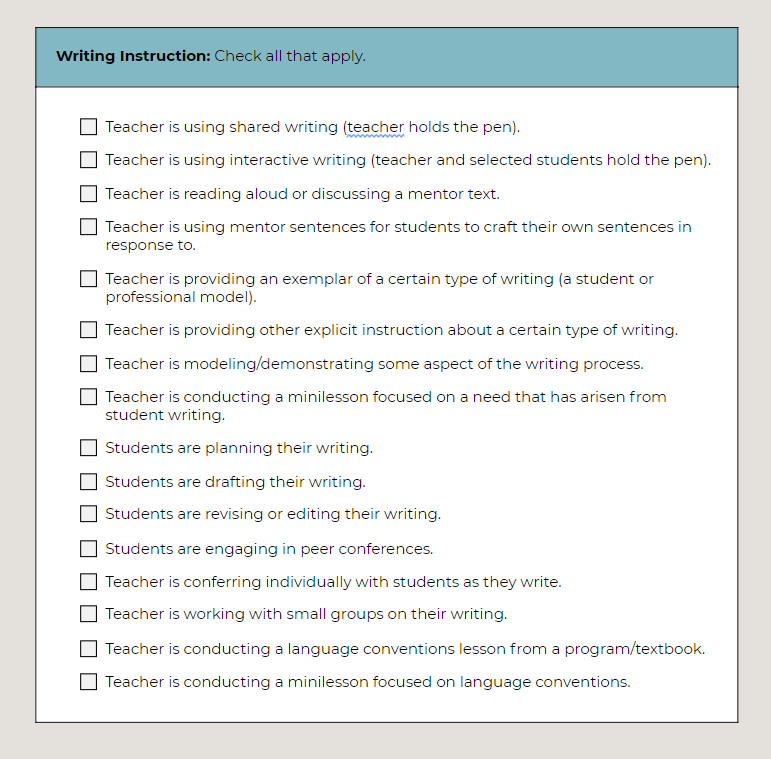

Elementary: Writing Instruction

In the elementary years, students learn to express their ideas with correct spelling and fluent, legible handwriting. They need lots of opportunities to write in order to become both more competent and confident. Unfortunately, what I’m seeing in elementary classrooms is what Mike Schmoker has seen too—arts and crafts activities masquerading as writing instruction (see “The Crayola Curriculum” here).

The tool below focuses on the writing process and specific, effective strategies (shared writing, interactive writing, mentor texts, etc.). It’s a succinct guide to help everyone remember and look for evidence of best practices.

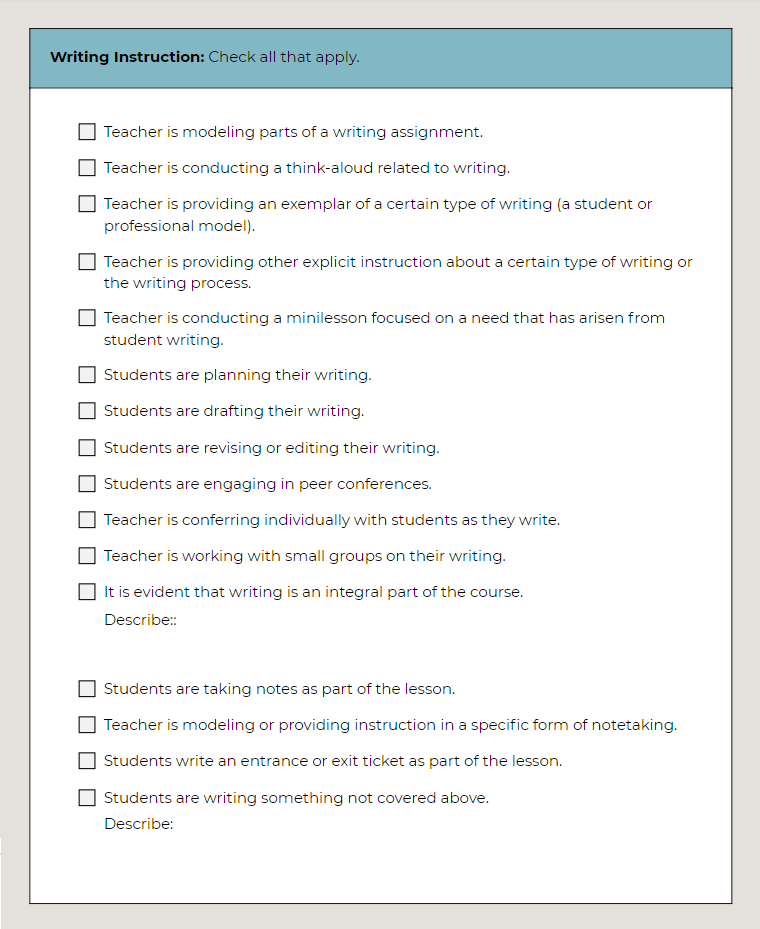

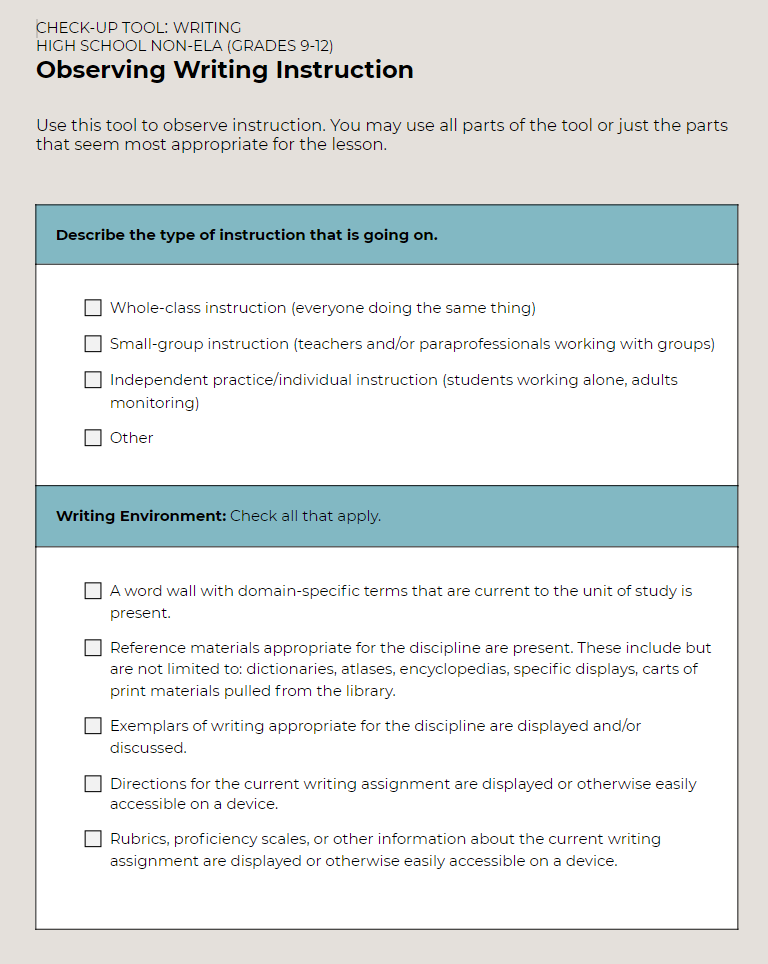

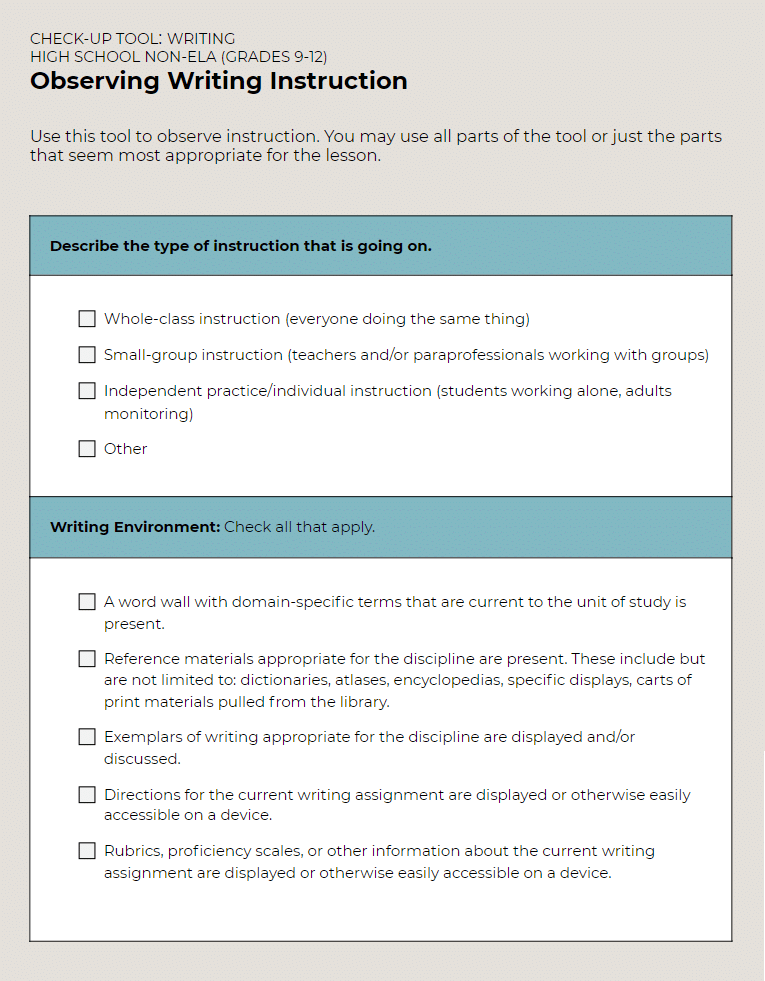

Middle and High School: Writing Instruction

Sadly, I see a fair amount of non-writing occurring at the secondary level as well. The most common fake writing assignments are poster-making and report-writing that consists of copying and pasting gobs of material from various websites. Students do these assignments with little conversation among themselves and with very little initial direction or ongoing feedback from their teachers.

This tool focuses on effective instructional strategies, like modeling the type of writing expected and conferring with writers to provide feedback. This tool is most appropriate for English language arts classes; in the book, there are also tools for non-ELA classes, as shown in the next example.

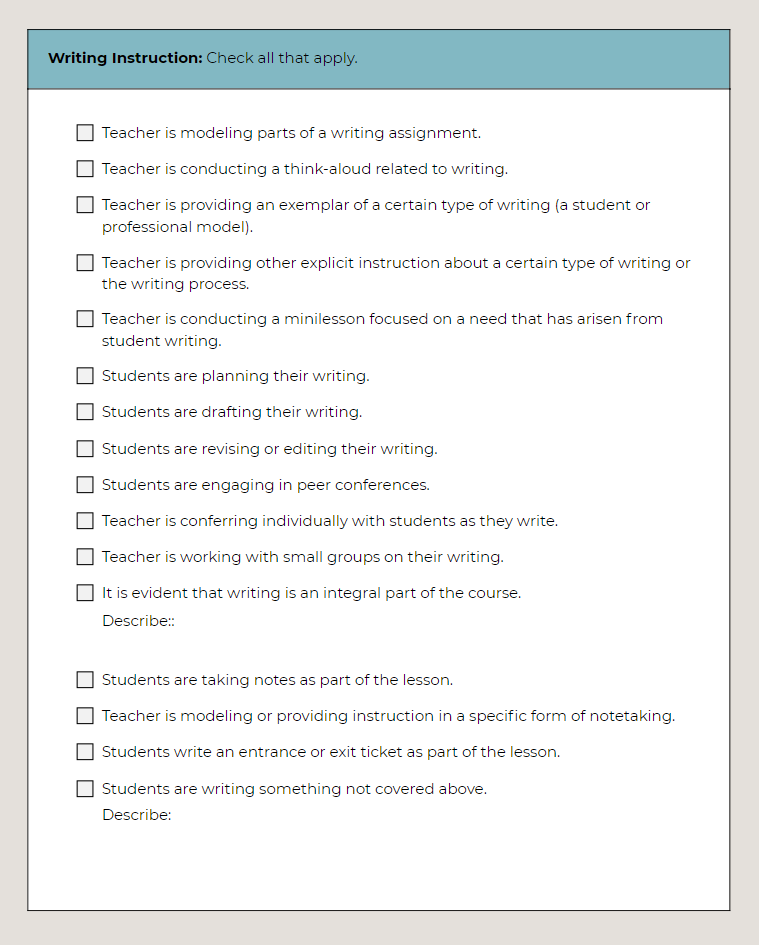

Middle & High School Non-ELA: Writing Instruction

This tool is designed to be used in non-ELA classes and combines environment and instruction. This tool makes clear that when assigning writing in any class, the use of exemplars and rubrics is necessary. It also reminds teachers that resources like word walls and reference materials are needed in all classrooms to support content-area learning. This tool would be excellent to use if your school is engaged in cross-curricular literacy efforts — or if you want to be in the future.

Where to Start

If you want to conduct a literacy check-up in your school, get started in one area. Perhaps literacy learning environments have been neglected during the past year and need to be revamped. If so, you can start with the environment tools. Or perhaps you’ve spent the past couple of years implementing a new elementary reading program. If so, what has been done for writing? Has it suffered from a lack of care? Use the tools to find out. Or, if your school or district wants to go big and bold, you can have my consulting team come in and collect baseline data in all the areas covered in the book – environments, reading, writing, speaking/listening, and research/technology. We would work hand-in-hand with your leadership team so that you can all understand and act on the data.

We all know the adage, “What gets monitored gets done.” It’s not a surprise to me that teachers are handing out a lot of worksheet packets, playing too many videos, and having kids cut, color, and paste in their English/reading classes. It makes clear that the monitoring of effective literacy instruction has fallen by the wayside. It’s time to refocus.

We educators have had a year like none other, and we are finally back with our students, in a situation as much like normalcy as it can be. What better time is there to do what works best? As administrator Jay McClain says, “As we come out of the shock of our crises, we have an opportunity. We have a choice. We can choose to be awakened, to come out of the wilderness… Or we can choose to pretend this never happened and revert to what wasn’t working. The choice is ours.”

References

Hunter, M. (1982). Mastery teaching. El Segundo, CA: TIP Publications.

McClain, J. (2021). A found year. Unboxed. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://hthunboxed.org/unboxed_posts/a-found-year/.

National Center for Education Statistics. (1994). Literacy behind prison walls: Profiles of the prison population from the national adult literacy survey. Retrieved May 12 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs94/94102.pdf.

Neuman, S. B. (N. D.) The importance of the classroom library. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from http://teacher.scholastic.com/products/paperbacks/downloads/library.pdf.

Schmoker, M. (2019). Focusing on the essentials. Educational Leadership. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept19/vol77/num01/Focusing-on-the-Essentials.aspx.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Hi Jennifer-

I’ve been listening to your podcast for years and absolutely love it! When you shared your interview with Kareem Farah, I looked up the Modern Classrooms project and took it to my principal. This summer, I’m working with a cohort of teachers as we use it to develop a unit of instruction in each of our classrooms. We’re uploading our units to a sandbox course in Canvas (our district’s required LMS) so that we can give each other feedback. All this to say- I love your podcast and I’m consistently inspired to implement what you share in my own class and school (I’m a high school art teacher).

I wish I had posted this comment back when I would have stopped after that last sentence. Today, I listened to “Does your school need a literacy checkup?” and found myself cringing through the first 15 minutes. I agree that there is a time and place for screens vs. no screens and that has to be thought through, but I kept waiting to hear that. So much of my content is now delivered via self-paced learning through videos I’ve made and content that I’ve written or curated. And because of that, I’ve freed myself up to have more individual and small group time with my students… so I cringe to think that a colleague or admin may hear this and think that if they walk in my room and see multiple students on a screen, that they’re not engaged. Also, I don’t use packets in my own classroom, but I do believe it’s possible for a teacher to create a highly engaging, thought-provoking packet… especially if it’s broken up with pair/group/whole-class activities throughout its completion.

So… to be honest, Jennifer, this feedback really isn’t for you- it’s more for Angela Peery. I work in a school that is in desperate need for literacy strategies and began listening with high hopes, but the first 15 minutes really turned me off. I’m the teacher that’s positive to a fault (I’m sure I annoy my colleagues) in PD; I look for inspirations that I can translate to my own work, even if it appears to be unrelated on the surface. So, if I’m cringing and feeling defensive at the start, there are probably others feeling the same way. If Dr. Peery happens to read this comment… please be careful when presenting things you’ve seen in the extreme. I’m sure you know that it’s possible to make an engaging, thought-provoking worksheet, even if less common. And I’m guessing that you believe that technology can be used to enhance our curriculum, and even literacy. Be clear that you are not saying that those strategies can’t be fabulous, but that students also need human interaction, and that can’t be replaced. I think that may be what you were trying to say, but when I got defensive, that isn’t what I heard. I hope you’re able to take the feedback well; I think what you do is very important. Increasing literacy has been part of our school improvement plan in some form or other since I’ve been there, and we still haven’t seen meaningful, sustained growth.

Hi Windy! You are so skilled at giving kind, thoughtful feedback. I totally see your point, and yes, I think Dr. Peery was describing more extreme situations. It’s interesting that you mention Modern Classrooms, because when we were talking about screens, I was thinking about how I myself have pushed for more pre-recorded content and how the MC approach is built on that. In your comment and in my conversations with Kareem Farah, there is an emphasis on what ELSE can be done when time is freed up with recorded content—that’s the piece I think is missing from some classrooms, particularly those that Peery has observed, and it sounds like you’re doing all of those things. I remember having these thoughts, but we had a lot of ground to cover in our interview; this is probably why we skipped over some of the nuances that would have made you feel seen.

On a side note, I absolutely love hearing about the work you’re doing to set up self-paced learning in your school, especially the part about giving each other feedback. That is incredible. I hope you are able to come back to this post at some point and pull some things that will help you fine-tune what you’re already doing.

Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts.

Hi Windy, and thank you for your thoughtful comments. Of course I understand that there are a lot of excellent and reflective teachers out there; I have the privilege of supporting many of them! I agree with you that worksheets, screen time, and other methods/tasks can be done extremely well. However, what I’ve seen over and over again in more than 1000 random observations is a preponderance of such tasks NOT being done well. That’s the evidence I’ve collected and the evidence I was speaking to, and that’s the evidence that compelled me to write the book. Perhaps the first 15 minutes of the conversation with Jenn sounded more negative than I intended; unscripted conversation between two people has different effects on different people, obviously. My hope is that the podcast episode causes other educators out there to reflect as deeply as you have and talk with their colleagues about the issues I raised.

I appreciate these comments because as I listened today I felt frustrated. How was I to reconcile this podcast with the ones about Modern Classrooms that I’ve been digesting and working on implementing. I would really love to hear a follow-up podcast about this topic from the always articulate Jennifer Gonzalez.

Hi Angela,

Thanks so much for your article reminding us of the importance of literacy education. I particularly liked your point about literacy not only leading to adequate reading and writing, but giving students the skills to share information more effectively, defend themselves, think critically about information and its source, seeking meaningful answers to their questions and taking into account global perspectives when introduced to new information.

Your points about improved literacy education being as simple as the environment around our students really hit home. I looked around my classroom and noticed my empty display boards where I should have student writing, books of the week, and prompting questions and quotes displayed to encourage creative and critical thinking.

I have a question for you. When approaching a more well-rounded literacy education, what are some of your favourite assessment tools to properly gauge whether or not students have gained these real-world skills listed above? Rubrics are great and all, but I want to create an environment where students are using literacy to explore their education and become better members of society, and not to gain a letter or number grade. Your checklists are a fantastic start. Any suggestions?

Thank you so much for such a great article!

Jen

Jen, wow! Thanks for your thought-provoking question. I can’t say that I have found effective assessment tools like you mention, but I have seen teams of teachers create their own tools that work for them. I think that’s really the best way to assess students’ literacy growth and literacy skills — for colleagues to get together and hash it out.

I’m so glad to hear about your reflection on the learning environment. There are small, easy steps all of us can take to enrich the environment for our students! Please stay in touch. I’d love to see photos of what you do in your room. My email is drangelapeery@gmail.com.

Thank you for this post. As a school librarian at a middle school I was disheartened, however, to see no mention of the school library and it’s role in creating an environment of literacy at a school. A well stocked and staffed school library can be invaluable in creating lifelong readers, critical thinkers, excellent researchers, and empathetic global citizens. And an active and well-trained school librarian can be a catalyst for many of the best practices throughout the school that were named in this article. When taking inventory of the literacy environment you are creating at your school, please do not neglect the school library, and make sure you have a credentialed librarian!

Hi Amanda. Although we didn’t discuss school libraries specifically on the podcast, during literacy audits, we focus quite a bit on the resources, policies, and procedures of the school library program. We even give every school or school system a detailed report on the library program, created after we visit each library (multiple times) and interview all the LMSes and library paraprofessionals. You are so right that the LMS is critical in promoting literacy on every campus! Thank you for reminding everyone of that!

Hi Jennifer,

I will be returning to 7/8 ELA in August. I found this article helpful (as are the above comments). The points made affirm that my emerging implementation plans are on the right track, so thanks to both of you! My one question involves the middle/high school checklists at the end — they both say “Non-ELA” and I’m wondering if the ELA version could be posted?? Thanks for the work you are doing!

Julie, per copyright/fair use law, my publisher allowed us to share about 10% of the tools that are available in the book. For the secondary level, there are ELA and non-ELA tools. If you’ll email me at drangelapeery@gmail.com, we can discuss what might be most helpful to you, and I can send you a couple of other tools if you like.

Hi Angela,

Just curious about how the Science of Reading and Structured Literacy fits into a school’s Literacy Checkup?

Melinda