Listen to my interview with Jen Serravallo (transcript):

Sponsored by Peergrade and Microsoft Inclusive Classroom

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

A few weeks ago, a teacher named Isabelle O’Kane sent me a direct message on Twitter. She had been reading a debate that was raging all over social media, and she wondered if it was something I might want to write about. The debate took place in response to a single tweet sent out by literacy experts Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell:

The classroom library should NOT be organized according to level, but according to categories such as topic, author, illustrator, genre, and award-winning books. #FPLiteracy pic.twitter.com/hxJNDow3Qz

— Fountas & Pinnell (@FountasPinnell) September 21, 2018

Teachers responded to the tweet from all directions: Some shouted hallelujah, because it supported what they were already doing. Others agreed, but argued that their hands were tied because administration required leveled libraries. Quite a few insisted that the best approach was to do both; yes, students should be able to seek out books based on interest, but without levels, how would they ever find appropriate books on their own? And some threw up their hands entirely, wondering if a single, clear answer was ever going to present itself.

Because my training and classroom work has all been with students in grade 6 and above, I don’t have a lot of experience or knowledge on this topic, but it definitely seemed like something teachers needed help with.

Jennifer Serravallo

So it was pretty serendipitous when literacy consultant and author Jennifer Serravallo contacted me right around that time about her new book, Understanding Texts & Readers: Responsive Comprehension Instruction with Leveled Texts.

In the book, Serravallo takes a deep dive into the question of how best to match texts to readers. She starts with a discussion of why we have leveled texts to begin with, what their original purpose was, and the missteps we often make as teachers when using them. Then she explores the levels themselves—for fiction and non-fiction—and unpacks the characteristics to look for in each one. Finally, she brings it all together, showing teachers how to combine their knowledge of text levels and students to assess student comprehension, set goals, and match students with books that are just right for them.

In our conversation, which you can listen to on the podcast player above, we talked about the mistakes a lot of teachers and administrators make in how they use leveled texts, and what they should be doing instead.

What Are Leveled Texts?

When schools first attempted to differentiate reading instruction, they did it with texts that were written specifically for that purpose, like the SRA cards that were popular in the 1960s and 70s. Although these programs offered different levels to match student readiness, “(they didn’t) actually offer kids real language structures or really interesting storylines,” Serravallo explains. “And kids were not able to read those with as much comprehension as real children’s literature.”

In the 1990s, a shift came when teachers started looking at ways to level real books, books that were not written with “levels” in mind. Two types of text leveling emerged around this time:

Quantitative Leveling: Systems like the Lexile Framework leveled texts through computer programs that measured dimensions like text length and complexity.

Qualitative Leveling: This type of leveling is done by humans, and while it considers things like text length and complexity, it also takes more nuanced qualities into consideration, like whether a text delivers information in a purely straightforward way or contains multiple levels of meaning. One popular qualitative system is Fountas and Pinnell’s Text Level Gradient.

Common Mistakes with Leveled Texts

When leveled texts are used in classroom and school settings, teachers and administrators make some well-intentioned but significant missteps that can negatively impact students’ growth as readers.

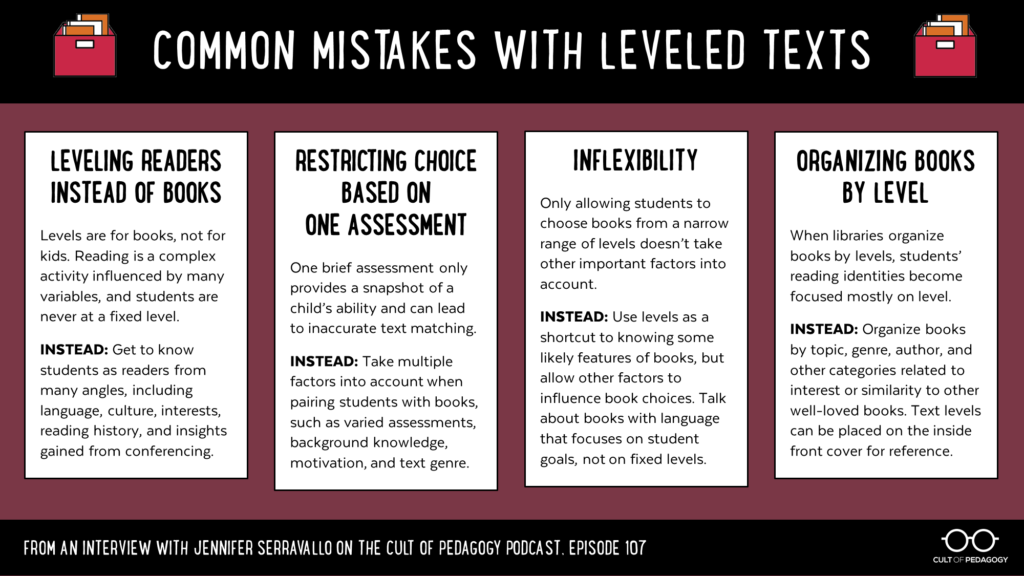

1. Leveling Readers Instead of Books

One of the biggest mistakes Serravallo sees is labeling students by text levels. “Levels are meant for books, not for kids,” she explains. “There’s really no point in time when a kid is just a level, just one. There’s a real range, and it depends on a lot of other factors.”

This misstep, she says in her book, has had negative consequences. “Kids nationwide have become aware of something that many would argue they shouldn’t be aware of at all…causing some students to compete, race through levels, and experience shame.”

To compound the problem, a number of schools have begun basing student learning objectives (SLOs)—part of teacher evaluation protocols—on these levels: “(Districts will) say, ‘You come up with goals for your students, and then we’re going to measure and make sure you met your goals.’ And what’s happening is that I find teachers are using levels (to measure growth)—’This student’s starting off at an L and is going to end up at a P,’ or something like that.”

This type of system often prompts teachers to put books in students’ hands that they’re not quite ready for. “The teacher is going to be pushing the student into harder texts in order to meet the goal,” Serravallo says. “You’ve got this kid being pushed through because they can maybe decode the text but not because they’re actually getting everything they can from it in terms of comprehension and meaning making. If the kids are not thinking on that level, why be pushing them into harder and harder books? Why not work with them in texts that they choose to help them get more from the texts that they’re reading?”

What to do instead: Rather than focus narrowly on text levels, teachers should get to know students as readers from a variety of angles. “Factors such as motivation, background knowledge, culture, and English language proficiency should all be on our radar when considering how to help students find books they’ll love, and how to evaluate students’ comprehension and support them with appropriate goals and strategies.”

2. Restricting Book Choice Based on a Single Assessment

“One of the ways that levels get misused is that teachers administer one assessment,” Serravallo says. “It’s usually a short assessment. It could be a computer assessment that’s a short text with multiple choice, it could be a running record where kids read a selection of a text and answer a few questions. So there’s this one assessment, and then from that they get a level or a level range, and they say to the kids, you can only pick from that level range. But the problem is that’s misunderstanding all of the different variables that kids bring to the table, things like motivation, prior knowledge, stamina, their command of English, the genre. There’s so many variables.”

What to do instead: Take multiple factors into account when pairing students with texts. “We need to look at a couple of different assessments,” Serravallo recommends, “and we need to account for these variables, and then once we have a sense of about where kids are able to read, we still need to be flexible when they go to choose. So if I have a kid who knows a lot about dinosaurs who typically reads books around Level O-P, if it’s a dinosaur book and he wants to read it, and it’s a Level R or S, maybe that’s okay.”

3. Inflexibility

Even if we have a pretty thorough idea of what types of texts would be a good fit for a student, only allowing them to choose books from a narrow range of levels doesn’t take other important factors into account. There may be times when a student wants to challenge herself by going for a book that will require more support to get through, and other times when students want to read an easier book for fun.

“Saying to a student, ‘You are a Level __ so you can only read Level __ books’ is deeply problematic,” Serravallo writes in her book. “We can use reading levels to help guide student choice, but levels should never be used to shackle a reader.”

What to do instead: Use reading levels as a shortcut to knowing some likely features of books, but allow other factors to influence book choices. In her book, Serravallo shows us how to adjust our language to help students make these decisions for themselves: Instead of saying something like, “That book is too hard for you,” she recommends saying something like, “That book is harder than what you typically read. Let’s think about how I/your friends can support you as you read, if you find you need it.”

4. Organizing Books by Level

While Serravallo admits to organizing the books in her classroom library in leveled bins years ago, “I’ve changed my thinking after seeing the consequence of what that does to kids’ reading identity. What ends up happening is kids go to the classroom library and they say, ‘I’m a Q. I’m going to pick a Q book.’ And they go to the Q bin and they only look in the Q bin.”

What to do instead: “I would organize them by topic, by genre, by author,” Serravallo says, “So the first thing kids see when they go to the library is identities. And they think about themselves first before they think about level: Who am I as a reader, and what am I interested in reading?”

For her own purposes, Serravallo would still keep text levels on books, but put them in an inconspicuous place on the book, like on the inside of the front cover. “That way, when a child is holding a book, it’s not like everyone can see the level on the book, so it’s a little bit more private. But I like that having them on the book, because if I haven’t read that book, I can peek at the level and be like, oh yeah, okay. Complex characters in this one. And I can use that to guide my discussions when I’m working with kids.”

To learn more, check out Serravallo’s book Understanding Texts and Readers, join the Reading and Writing Strategies Community on Facebook, or visit her website at jenniferserravallo.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

So glad to have read this! I’ve been having this discussion with admin for a few years now. Just because a child is a fluid reader for AimsWeb doesn’t mean that they should be reading above that Lexile. We have students who can read very rapidly, with few errors, but their comprehension is zero and they aren’t developmentally ready for those higher levels. I feel validated.

I’m so glad this helps, Nancy!

Hello! By any chance in this conversation did you come across a list or guide to what traits fit each lettered level? I keep hearing, “Oh, level ___, complicated characters” but I have not found information like this for higher levels, only lower elementary levels. I would love to know characteristics/skills that match higher levels such as M-Z. If you know any sources it would be greatly appreciated. Thank you! Jen Armstrong, 8th Grade ELA

Hi Jennifer! Yes, that information is all in Jen Serravallo’s book that I refer to in this post. There’s a HUGE section that goes through each level for fiction, and then again for non-fiction, describing the characteristics in a two-page spread for each level.

Jennifer’s book doesn’t go as high as I need for 7 & 8th grade. I have been using The Fountas & Pinnell Literacy Continuum: A Tool for Assessment, Planning, and Teaching published by Heinemann. It REALLY helps get a better grasp on each level.

I’d love to hear more about this Catherine! I too am with middle schoolers and find much of the material on reading intervention is for younger kiddos.

Thanks, Jennifer, for addressing this hot topic, which is also continually discussed among School Librarians. We are completely on board with you and Jennifer Serravallo, but we’re often overruled by administrators and/or teachers who misunderstand the purpose of leveled texts. Having your strong voice support successful reading strategies makes a huge difference for all of us!

BrP

This is one of the biggest reasons I wanted to share this!

This is so interesting to me as a world language teacher. We have moved to a proficiency-based model so we choose texts that are high-level and adjust the task to the reader’s level, not the text itself. When I first started teaching in 2008, language teachers would write or find texts that were written for a particular level. We would simplify or “level” the Spanish language. Of course, we have students who can already read (my youngest are 6th grade), but it’s still interesting to see how important the other factors (like motivation and interest) are to a reader in ANY language and at any level. I thoroughly enjoyed this piece!

As another school librarian, I am on board with the idea that we need to look at individual kids as individuals, not as a level. Be sure to keep your librarians in mind–we often HAVE read the books and if you are able to describe the reader (struggles with vocabulary, likes fantasy) we may be able to suggest something. Thanks for having this conversation.

I am so glad you discussed this topic with Seravallo – I love her reading and writing strategies books! I agree with her first 3 stances on reading levels, however I think leveling the library for very young readers is essential. I teach ELA to grade 2’s in a French Immersion program. That means I only have 50 minutes per day for reading, writing or word work. In the beginning of the year more than half the class reads levels A-D. I use a reading workshop model and if I let them loose” in the class library most students would pick books they couldn’t read at all – PINKALICIOUS or similar titles are always more enticing than beginning books. What I try to do is to get everyone close to level G-I and then I do away with the levelled bins. I agree it is best when the students curate their tastes, but when time is so precious I first need the levelled bins to get them over a hump. Thanks for taking on a primary grade topic!

Please watch this presentation on the importance of lesson to text match for a deeper understanding of the importance of decodable text:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRhKsFHMEuw&t=1449s

I remember back to when I was in school. It was extremely difficult for me to wrap my head around reading groups and it made all of the students involved uncomfortable. I was in a higher reading group and I felt guilty because my friend was in a lower reading group which made her feel stupid. I think there are ways to differentiate reading without embarrassing students. One great resource for teachers is newsela! It helps you send out interesting news articles for your students to read, but you can differentiate which versions of the same text get sent to which students so that if you have children with disabilities, ELLs, or someone that just has trouble reading you can still include them without overwhelming them!

I work with Secondary ELL where leveling takes on a different twist: level of language ability and level of familiarity with the content. One of my favorite tools is NEWSELA. They are available for free online and downloadable. They come in a variety of topics and there is a library with everything from Sports to current events to Literature all in 5 “generic” levels. From the content perspective, everyone is reading/talking about the same topic in discussion groups and doing similar exercises. I can do one general introduction to activate background knowledge and in the end…nobody feels singled at as “the slow kid.”

I REALLY appreciate the fact that you summarise the main points of these podcasts, because it is much more efficient for me timewise. Great points here and helpful for someone trying to work out the best approach for reading interventions.

Thanks so much!

Hi Jennifer,

First of all, I am new to Cult of Pedagogy but I have to admit that within the short time of being an avid reader/podcast listener, I have come to also be a huge fan of the site. The diverse topics, visuals and perceptions are just what I need to feel supported in this education world. Thank you!

In regards to this post, Wow! I am overcome by thoughts not only about the mere topic of “to level or not” but the deeper roots that create such a question as well. The biggest ideas that I am working through right now are all related to the philosophy of education and curriculum designs implemented as a result of the teacher’s beliefs.

As a current Master of Education student and literacy support teacher, I have been trying to grasp the idea of organizing my class library by leveled readers or by topics, genres, authors, illustrators etc. What is the right answer? Well, judging by this post I am not the only educator trying to sort it all out.

This brings me to why are there so many different perceptions and ideas about this? As you mentioned, some educators “shouted Hallelujah”, some agreed, but felt their options were limited, some thought both were best and some just didn’t know. Were there any teachers that said, “No way Jose! I’m sticking to my leveled readers!” I imagine there must have been? Ornstein and Hunkins (2013) argue on p. 151 that how teachers “Contemplate education, curriculum, and curriculum design is influenced by myriad realms of knowing and feeling. Individuals draw from their experiences, their lived histories, their values, their belief systems, their social interactions, and their imaginations” (Ornstein and Hunkins, 2013)

I say all of this because Education is complicated and as Ornstein (1991) states on p. 108 “… no single philosophy, old or new, should serve as the exclusive guide for making decisions about schools or about the curriculum” (Ornstein., A., 1991). Our planning, instruction and assessment all stem from our conception of curriculum (Academic, Technology, Humanistic or Social Reconstruction) views which are influenced by our personal educational philosophies and philosophical beliefs (Essentialism, Perrenialism, Progressivism and Pragmatism) (Ornstein., A., 1991). When I look at the question “What are the best ways to level texts” and Fountas & Pinnell’s view of organizing libraries by categories not level, I see three very different educational philosophies being considered: Essentialism/Perennialism vs. Progressivism.

Classroom libraries organized by level:

As Jennifer Serrevallo mentioned in your post, leveled readers were first introduced to support classroom differentiation. It was an attempt at teaching classic disciplines in the classroom as quickly and efficiently as possible which was influenced by the educational philosophy of essentialism and perennialism. The assessment was based on the level achieved by the student, and planning was more or less developed based around what was presented in each level. My question is though, is this wrong? What if a teacher truly believes that a student should be taught reading based on an academic concept of curriculum? If the assessment shows progress in the student, then can we not support this idea as well?

Classroom libraries organized by category:

Jennifer Serrevallo then mentions she would organize books in her library by category so that students see themselves first before they think about the level. In my opinion, this is a very Learner – Centered curriculum design which is guided by a humanistic, and to some degree, a society conception of curriculum based from a progressivism and pragmatic educational philosophy. Planning is developed by the students interests and the assessment (I assume) would be guided more by comprehension and fluency. Again, however, would this classroom library tactic be wrong? Or is it just a different approach than organizing libraries by level? If the assessment also shows progress in the student, can we not support this idea as well?

When Fountas & Pinnell made their announcement that classroom libraries should NOT be organized by level, that was their opinion based off of their own philosophical beliefs. Is it wrong? I don’t think so, I just think that it is a very good example of how complicated our education system can be due to the diverse nature of humans and the beliefs that are instilled in them. Because of these foundations in curriculum, do you think we will ever come to a common ground on how to organize our classroom libraries?

References:

Ornstein, A., & Hunkins, F. (2013). Curriculum, Foundations, Principles, and Issues. New Jersey, USA: Pearson.

Ornstein, A. (1991). Philosophy as a basis for curriculum decisions. The High School Journal, 74(2), 102-109.

Hi Kara,

Wow – so many interesting thoughts! I had a chance to touch base with Jen Serravallo and here’s what she passed along:

Her interview with Jennifer and the blog post merely scratch the surface of the topic, and much more is explored in her book. Without reading the book (and the many many many research citations) she supposes that her stance could come across as simply an opinion or philosophy, but there is also research, and history, that’s important to explore. Which is in the book, but too much to put into a blog post.

Thinking about things as “right” and “wrong” can be limiting. In education, Jen finds there is rarely a universal right or wrong. This is a topic where there needs to be some flexibility and fuzziness, and making decisions informed by the philosophies, yes, but also the research, can be helpful.

The majority of Understanding Texts & Readers is actually about empowering teachers to understand more about books and about expectations for reader response within texts of varying levels and across genres, to guide their assessment, evaluation, and teaching of readers around comprehension. Jen thinks you may be really interested in reading more and learning from it and she hope you check it out!

If students are always more than one level, why use leveled text in the first place? This is what makes them misleading. There are levels within levels, and a kid will be able to read one N but cannot read another; or can read an N and P but cannot read an O. It’s disingenuous to say level texts and not kids when levels are inconsistent, and students are assessed throughout the year in guided reading groups based on these levels daily and given a benchmark 2 to 3 times a year. If the focus is more about genres, topics, skills, interests, etc, then leveled text are irrelevant. They serve no purpose besides being normal books with no letter on the back without so much hype. Doing an entire F and P benchmark assessment that does not give quality information is a waste of time. More specific assessments on skills should be given instead if that is what the goal is. Serravallo teaches the same strategies that supports what F and P does..using pictures to read and relying on context. Ironic for Serravallo and Fountas and Pinnell to say do not use leveled libraries or that the way they are used is the problem when your entire system is leveled and you support the strategies used to read them. Too much of trying to play both sides.

Hi, Lynn. You bring up several points that are discussed in the article. If you haven’t already, you may want to go back and re-read the post, specifically section 3 “Inflexibility” and section 4 “Organizing Books by Level.” These sections address how text levels are truly intended for teachers’ instructional purposes. If you are interested in learning more about the skills and instructional focus areas indicated by a level, another helpful resource may be Scholastic’s Text Level Indicators.