Listen to the interview with Andrea Castellano:

Sponsored by CoderZ and Edulastic

Any Lauryn Hill fans out there would instantly recognize the opening chords to her classic hip-hop song, “Doo Wop (That Thing),” but how many of us could explain the line, “Don’t forget about the deen/ the Siratul Mustaqim” without googling it? If you’re not familiar with the term, I can save you the search: Siratul Mustaqim is Arabic for “the straight path.” But why didn’t she just say that? It’s not by accident—she’s code-switching.

What is Code-Switching?

Code-switching. Some of us have heard of it, most of us have witnessed it, many of us do it on a regular basis. But what is it, exactly? Why do people code-switch? And what does it have to do with teaching?

Code-switching is the act of alternating between languages during conversation. (For the purposes of this post, language is used as an umbrella term encompassing forms of speech including formally recognized languages, dialects, and nonverbal communication.) Code-switchers seamlessly switch back and forth without pause, often starting a sentence in one language and ending it in another. Sometimes they insert words from another language in the middle of a sentence, a behavior referred to as code-mixing. And it’s not just words that change—when code-switching, people might speak faster or slower, louder or softer, mix up the pitch of their voice, change their laugh, and even vary their facial expressions and body language.

Why do people code-switch? Well, it depends. Code-switching is a very personal and complex behavior that occurs for a number of reasons. It’s used to clarify or emphasize a point, and at times, to elude eavesdroppers. Strong emotions can prompt a switch, as does a sudden change in topic. Sometimes a word simply comes to mind faster in one language. Other times it’s just simpler to say one word in another language (deen) than produce an English approximation on the spot (“living according to one’s religious principles”).

Code-switching helps us express ourselves in a way that makes sense for us at that moment. Some people code-switch in every conversation, while others use it more strategically, depending on the situation. For example, your children might speak one way with you but sound totally different when they’re off with their friends. People who code-switch are experts at navigating social situations and determining how to use language to our advantage. It helps us stand out; show who we are, unequivocally and unapologetically. It’s how we establish community—a greeting of ¡Hola! or Assalamu Alaikum instantly signals cultural or religious solidarity. Conversely, people code-switch to assimilate, downplaying or modifying their natural speech to fit in where they’re made to feel they don’t belong.

Code-switching is both art and tool, subtext and premise, bridge and platform on which we build a conversation. Code switchers use language to deliver ideas with efficiency and style. When Ms. Hill called in her Muslim fans in that lyric, she chose the language of Islam to speak directly to them. That choice served her both lyrically and linguistically, expressing a complex idea to a specific audience in a single word. And with it, she reminds us that because we matter, so do our words.

Why Language Matters

Language is identity. It shapes and informs our thinking, our values, and our relationships. It binds us to our roots and informs how we interact with the world. This should be reflected in our teaching. Gloria Ladson-Billings says, “The goal of cultural competence is to ensure that students remain firmly grounded in their culture of origin (and learn it well) while acquiring knowledge and skill in at least one additional culture” (Ladson-Billings, 2014). Code-switching is a feature of that multiculturalism, a skill set to be nurtured and developed. Language-affirming practices help us better understand what our students need to learn and grow.

The trouble is that not all students feel they can bring their whole selves into the classroom. Even the most well-meaning teachers can unwittingly do more harm than good. Many bicultural and bilingual children report experiencing a sense of loss when they acquire their second language (Casesa, 2013) and it’s not by coincidence that their educational setting plays a part in this. Over and over again, students are interrupted, corrected, and told to speak proper English by their teachers. This seemingly benevolent practice has long-lasting negative effects on many of them long beyond their school years.

Black English and the Culture of Power

Often when we think of multilingual learners (MLLs) we think of immigrants or children of immigrants who speak languages other than English, but many code-switchers actually speak a dialect of English as their heritage or home language. Despite there being no official national language in the U.S., one particular version of English has become so synonymous with academic language that not only is it the preferred dialect for reading, writing, and speaking, but other dialects are viewed as inferior. This has mostly to do with how dynamics of race and culture affect our perception of language.

In her 2020 book, Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy, Dr. April Baker-Bell explains how racism and linguistic injustice are linked. She says the white mainstream dialect known as Standardized English is held up as a model language while Black English or AAVE (African-American Vernacular English)—though widely spoken—remains underutilized and underappreciated in academic settings. Even though Black English and other racialized dialects do not exist in opposition to academic language, the students who speak them are discouraged from speaking their heritage languages in school, and their bilingualism is rarely viewed as an asset.

Why are certain languages treated differently? For one, it’s still widely believed that Black English is simply slang or informal speech, when the fact is it has its own grammar, syntax, and vocabulary like all other languages (Kamm, 2015). Another common line of thinking is that Black students need to code-switch to better navigate the academic or corporate world later on (Baker-Bell, 2017). This is a response to what Lisa Delpit describes as “a culture of power,” in which marginalized people learn to code-switch for survival instead of as a means of self-expression, feeling they have to speak a certain way if they want to get ahead (Delpit, 1988).

Though code-switching can be an effective way to gain access to traditionally white-dominated spaces, the downside of this type of survival code-switching is Black children are being taught to leave parts of themselves behind when entering academic or professional spaces, and by continuing to uncritically affirm the dominance of Standardized English (Lippi-Green, 1994), we reinforce it as the norm.

Here’s where examining our own implicit biases is crucial. Do we think of language in terms of “right” and “wrong?” Constantly fight the urge to correct people’s grammar or dismiss someone outright because they sound “uneducated”? Equate English speaking (especially non-accented English) with being American? A bulk of this harmful thinking is the result of our own schooling which we now as adults have to work to unlearn.

We should want better for our students. The fact is, code-switching is not a sign of linguistic incompetence, but a normal occurrence for a multilingual brain. (Yuhas, 2021). Rather than attempt to micromanage how they use their language, we can guide students to the realization that they can decide for themselves when and how they code-switch.

Setting the Record Straight: Common Questions About Language in Schools

Let’s be honest. Sometimes it feels like as soon as we’ve begun to master this teaching thing, another element gets thrown into the mix that has us feeling like a rookie all over again. Adding strategies that specifically address equity of language into our repertoire may seem like a daunting task, but if we know it can help our students, it’s worth a try. Hopefully in time it will become clear that even small changes can have a big impact.

My students need to learn English, and fast. Won’t code-switching slow down their progress?

Short answer: it won’t.

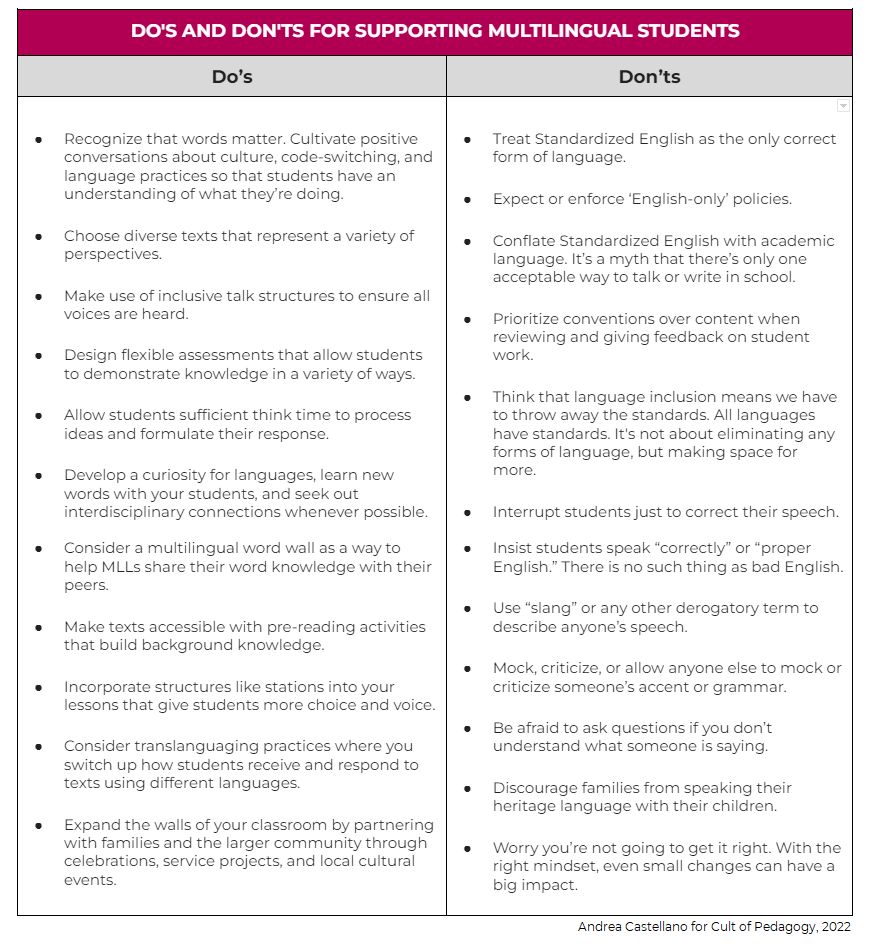

If you want to create a language-inclusive classroom for your multilingual learners, don’t expect or enforce “Standardized English only” policies in your classroom (Ethical Englishes, 2019). It’s fine to encourage them to take risks, but actively limiting or making rules about how they’re allowed to talk will shut down communication and damage your relationship with them.

It’s a myth that allowing students to speak their home language in school slows down their acquisition of English (Kamenetz, 2019). Regular practice of both languages will help maintain their bilingualism. In the beginning stages, use scaffolds to make the material more accessible. They’ll eventually transfer their conceptual understanding to their new language once they have the vocabulary.

If I don’t correct my students when they make an error, how will they learn?

Short answer: It’s fine. Just let them talk.

Some believe we should take every opportunity to address errors. We even have a term—teachable moment—for stopping to correct a student in the moment. But cutting someone off in the middle of a thought is not only an ineffective instructional tactic, it’s disruptive to the flow of conversation. It’s unnecessary to interrupt their train of thought just because they said “goed” instead of “went.” They probably won’t remember the correction anyway, and their classmates who were listening attentively also have to refocus. If it truly is an error (and not a language difference) you can always make a mental note to do a lesson on it at another time.

What about the standards?

Short answer: Yes, you still have to teach the standards.

While it’s true we have English language standards in our curriculum, we don’t need to prioritize Standardized English at the expense of all other forms of language. Making space for linguistic diversity doesn’t mean eliminating what already exists; it’s about creating a balance. Teachers can teach the standards without asking students to compromise their identities, and ultimately, language-inclusive instruction will only advance rather than jeopardize their academic growth.

I only speak English—won’t that limit my ability to do all of this?

Short answer: Start with a curious mind.

You don’t need to be able to speak every language in order to support students who code-switch in our classrooms. Showing genuine interest in your students’ language skills can go a long way. Also, demonstrate an appreciation for languages in general. Whether you teach history, music, or algebra, there are plenty of interesting and fun connections you can make to your subject area.

Instructional Practices that Support Multilingual Learners

Multilingual learners (MLLs) are often assumed to be at a disadvantage in a school setting, but this cannot be further from the truth (Bialystok, 2011). Nor are they a monolith: Every one of them comes to us with unique strengths, needs, and gifts. That’s why there’s no single strategy that works for everyone: Some of the following suggestions will feel more appropriate for learners of English as a new language while others make sense for more fluent speakers. As always, do what makes sense for your particular class.

Get Them Talking

MLLs need lots of opportunities to engage in meaningful conversations in class. This can be challenging if they tend to sit quietly during discussions and let others do the talking. Sometimes they’re just listening, but other times fear of critique or correction truly stops them from participating. If we want everyone talking, we need to build inclusive talk structures into our lessons.

To do this, vary the different types of discussion. Students who never raise their hand in whole class discussions will open up once they’re in a small group, while others prefer to share their thoughts with a trusted partner. Offering variety in talk structures increases student-to-student interactions and generates opportunities for us to informally assess understanding, but most of all, it lets students talk in ways that are comfortable for them.

Processing ideas can take longer for students used to speaking two or more languages, so we need to make effective use of “think time.” That’s when you ask a question and pause. Don’t rephrase the question. Don’t call on anyone. Let students absorb the question and formulate an answer. This is especially helpful for MLLs because they often have to mentally rehearse their response before saying it out loud. If they appear hesitant, see if they need more time and then circle back after the next speaker. Once they do start speaking, resist the urge to interrupt or speak on their behalf. If there is any confusion, you can always ask them to repeat or rephrase, but more often than not, those few extra seconds can be a game-changer.

Make Text Accessible

The literacy block is typically one of the most demanding times of the day for multilingual learners. Many encounters with texts end in frustration and confusion because students weren’t properly supported throughout the lesson. Not only do they need multiple chances to absorb new information, three additional points to consider when making a text accessible are background knowledge, representation, and means of delivery.

- Background Knowledge: If students are having trouble accessing informational texts, consider pre-reading activities that activate and build background knowledge. It may be useful to show a short video or have students click through a slideshow of images related to the topic. Have them preview key vocabulary words they’ll find in the reading (ideas for building vocabulary are linked here). Take time during lessons to identify cognates or root words related to the topic. A multilingual word wall is also a great way to help MLLs share their word knowledge with their peers. New words can be collected in a personal dictionary as a side project.

- Representation: Part of making texts accessible is choosing stories our students can relate to both in terms of language and message. We should be regularly selecting culturally diverse texts, especially those that use languages or dialects other than Standardized English. In addition to learning about other cultures, students should see themselves reflected in the literature they read. We also need to vet our instructional materials for potential issues with the representation or portrayal of cultural and racial groups. There are a lot of questionable resources out there—be vigilant!

- Means of Delivery: Multi-modal instruction makes content engaging and accessible to all our learners. Station teaching is a perfect way to differentiate for MLLs using varying levels of text complexity. One way this could work is while one group reads a grade-level text, another group can have a simplified version of the same text. (Newsela offers texts in multiple languages and on differing Lexile levels for this exact purpose). Combine that with a video station and a vocabulary station and you have a robust multi-modal work session that can be repeated at any time with a new text or topic.

- Additional Scaffolds: If students are not yet proficient enough in English to follow along, they can still participate in other ways: Providing translations of text or subtitles in a video can help students keep up with the material, and offering credit for work in languages other than English is always an option, too. They may benefit from a paired text or video or some other way to reconnect with the material. Later, have students review what they’ve learned using retrieval techniques (listed here) to solidify concepts and help make new words stick.

Be Flexible with Assessments

When so many assessments require a level of English proficiency that may not even be relevant to the assignment, how do we ensure we’re getting an accurate snapshot? By using a variety of assessment formats such as open-ended prompts, performance tasks, or projects and adjusting our own assessments to ensure they’re culturally relevant.

You can also employ flexibility in reviewing and grading students’ written work. Focus the majority of assignments on content, not conventions, and remember variations in language shouldn’t result in a lower grade. Obviously, every language has grammar, syntax, and spelling conventions that can be taught, practiced, and mastered, so this is not to say conventions don’t matter. It’s just that not all assignments need to be graded against the conventions of Standardized English. If a student shows consistent need for explicit instruction with grammar or spelling, you can always offer targeted instruction during small group lessons.

Finally, progress-based assessment criteria such as checklists and rubrics clarify your expectations for each task and make feedback actionable. It’s especially helpful to co-create those with your class. Not only will they have a better idea of what you’re looking for but they’ll be encouraged by seeing what they already can do.

Translanguaging

If you’re looking for a bolder way to incorporate students’ existing language abilities into your lessons, translanguaging is a great way to develop literacy skills in multiple languages (España & Yadira Herrera, 2020). That’s the practice of designing activities to allow students agency over their languaging practices. For example, students might read a text in Spanish and respond to a discussion prompt in English. This gives them access to the material while supporting their conversation skills. Or, they might watch a video in subtitles, discuss what they learned, and write a response, all using both languages. The idea is that alternating between forms of input, processing, and output supports fluency in multiple languages at once. The advantage of translanguaging (Otheguy, García & Reid, 2015) over code-switching is that it eliminates any artificial or teacher-controlled separation of languages.

Other Inclusive Practices

In addition to the instructional strategies outlined above, there are a handful of other practices that might happen more casually alongside the pedagogy. Creating language-inclusive classrooms is more than a technique; it’s a mindset.

- That mindset means we never mock or criticize anyone’s accent or grammar. It means we support our students’ languaging practices. It means moving away from the idea that there’s a right and wrong way of speaking, that Black English and other dialects are “slang” or “informal” versions of the true and proper English. It means affirming, not just tolerating, language diversity.

- An inclusivity mindset also means expanding the walls of the classroom. Field trips, service projects, and community events are a great way to tie learning to the real world. It means inviting families to publishing parties and heritage celebrations. It means conversations without judgment and relationships that matter.

- Inclusivity means we make space for diversity: diversity of thought, experience, culture, language, and more. It means we make sure our students know they belong.

“Respect is Just the Minimum”

As we commit to becoming more culturally responsive educators, we need to not only respect, but nurture and protect our students’ cultural, racial, and linguistic identities. How we talk about language and what we allow (and don’t allow) to go unchallenged in our classrooms is hugely influential and the choices we make as teachers carry weight. We may not always know the right thing to do in every situation, but as long as we make ongoing, conscious efforts to include all voices in the conversation, well, we’re on the right path.

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2017). I can switch my language, but I can’t switch my skin”: What teachers must understand about linguistic racism. The guide for White women who teach Black boys, 97-107.

Baker-Bell, A. (2020) Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. (1st edition). Routledge.

Bialystok, E. (2011). Reshaping the mind: the benefits of bilingualism. Canadian journal of experimental psychology = Revue canadienne de psychologie experimentale, 65(4), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025406

Casesa, R. (2013). “I Spoke It When I Was a Kid”: Practicing Critical Bicultural Pedagogy in a Fourth-Grade Classroom. Schools: Studies in Education, 10(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1086/673329

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, 58(3), 280-298.

España, C. & Yadira Herrera, L. (2020). Heinemann Blog. What is Translanguaging? https://blog.heinemann.com/what-is-translanguaging

Ethical Englishes (2019, August). The Dangers of “English-Only” Policies (for ESL students) in School. https://www.ethicalesol.org/blog/hhryxasqrobl9b8gzcza24aj6x5w5q

Kamenetz, A. (2019). 6 Potential Brain Benefits Of Bilingual Education. Npr.org. https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/11/29/497943749/6-potential-brain-benefits-of-bilingual-education

Kamm, O. (2015, March). There Is No ‘Proper English’ Wall Street Journal.

Ladson-Billings, G.J. (2014). Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the Remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84, 74-84.

Lippi-Green, R. (1994, January). Accent, Standard Language Ideology, and Discriminatory Pretext in the Courts. Language in Society, 23(2), 163-198. https://rosinalippi.com/weblog/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Lippi-Green1994Accent-standard-language-ideology-and-discriminatory-pretext-in-the-courts.pdf

Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015, October). Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3): 281–307 https://ofeliagarciadotorg.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/otheguyreidgarcia.pdf

Yuhas, Daisy. (2021, November). How Brains Seamlessly Switch between Languages. Scientific American.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Could you send me a link to your podcast on Code-Switching? I loved reading about the topic, even though I have spent 30 years studying the concept and 70 years code-switching (LOL) your piece was still very interesting.

Hi, Patricia. There was a glitch on our end that altered the visibility of the podcast player at the top of this post. It should be all fixed now!

In the podcast I heard Jennifer pronounce Andrea’s last name “ca/ste/la/nos” (using the English L sound) although the standard Spanish pronunciation would be “ca/ste/ya/nos” (with the double LL getting a Y pronunciation). The last name Castellanos means Castilian (person from Castille) which is located in Spain and uses the modern Spanish language.

So, I was wondering if this is Jennifer’s pronunciation or Andrea’s preferred pronunciation.

Hi Corita,

You’re correct about the Spanish pronunciation of the name, however, it is also an Italian name, so in my case, Jenn’s pronunciation was correct!

What do you advise when other students pick up a dialect that is not theirs? For example, I have students born and raised in an area that is predominantly white, but since they like to hang out with black students, they begin to copy their ‘ebonics’. They think it’s cool, but from my observation, I don’t think the black students like it all that much. I don’t always know what to say that is not offensive.

Thank you for this question, Denise. While your students may not be aware, what they’re doing sounds a lot like cultural appropriation in language form. I’m linking a great resource here that addresses this exact issue and gives some concrete suggestions for how to handle it. Hope this helps!

We have a real problem with students using curse worse or what some would consider “crude” language in our classrooms and hallways. It is pervasive to the point that some teachers do not even address it. I have had students and parents defend this using cultural norms as the basis. Am I overreacting to think this is a big problem? Is there a culturally responsive way to address this?

Ginger,

It’s true that there are cultural differences in what is considered acceptable in terms of language, especially curse words. I don’t have the context of how curse words are being used by your students, but what your families are saying may be worth considering. It has been shown that student language is over-policed by teachers, leading to increased incident reports, visits to the principal, suspensions, and marks on their permanent record. And this happens overwhelmingly to students of color, especially Black students. We don’t want curse words to be the reason a student doesn’t graduate or get into their school of choice.

On the other hand, we don’t want students to use words in harmful or hateful ways. Setting boundaries about what kinds of words can be used continues to allow for freedom of expression without making anyone feel as if their humanity is being questioned. There is a list of words that qualify more as hate speech than curses and they have to do with race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, etc. As a school you can set the record straight about what particular words will not be tolerated, and this should not be seen as culturally irrelevant; in fact, it’s the opposite.

In addition, continue modeling and talking to your students about how we use language to communicate, express, and uplift each other. And of course, if you feel uncomfortable with certain language, you can always let your students know. If you have that mutually respectful and caring relationship, they should respond positively. Hope this helps.

Best, Andrea

Hello! Is there a transcript for your podcasts? I want to assign this one and a few others for a course I’m teaching, but I don’t see the transcript and will need to have it for accessibility. Thank you!

Hi Jennifer- first of all, thanks for sharing our work with your students! The posts that Jenn writes are more like summaries of the interviews, so transcripts are available of the more detailed interviews. However, when a guest writes a post, such as this one, the content is pretty much the same as the interview, so the post itself serves as an interview transcript. If you go to the post and scroll down, you’ll see a print icon alongside the post. Click on that and when you’re in the print dialogue box, you can also change the destination to create a PDF version. I hope this helps!

Hi Andrea,

I really love how learner-focused this is. School should be about helping all students reach their full potential! I have always strived to use rubrics in my assessment but I’ll admit they are something I have always struggled to create. Do you have any tips for producing a good quality rubric?

Also, you say to focus more on content and that not all assessments need to assess conventions of language. What percentage of assignments would you say you directly assess conventions vs not?

Do you ever use technology as a way to support students when you are assessing “Standardized English” conventions?

Thanks!

Tai,

Rubrics are great because they’re so adaptive. I happen to prefer the simplicity of the learning progression rubric detailed here in this post: Introducing the HyperRubric: A Tool that Takes Learning to the Next Level And because they’re based on specific criteria rather than arbitrary descriptors (numbers) you can adapt them to reflect your specific students’ learning abilities and goals.

This leads to your second question about assessing conventions. Regarding your tech question, I provide opportunities for practice on IXL and I-Ready during centers. That being said, while I do teach Standardized English grammar, with the exception of some published essays or other written work, conventions don’t appear on any rubric, and I don’t lower grades when students utilize non-standardized language. My focus is on my students’ word choice, craft, understanding of genre, and their ideas.

In the podcast, I thought there was a resource teachers could use to help with translanguaging resources for students to access. Could you reply with the resource or resources for translating articles and student work? I had a student speaking mostly Russian last year, and it was very difficult to support him. I used Chat GPT to help, but wondering if there is a better resource out there.

Hi Madeline, the resource I linked to in the article was actually a short list of suggested resources from Larry Ferlazzo. Here it is for quick reference. Hope you find it helpful!

Hi Andrea! I enjoyed listening to your podcast and found the ideas you presented to be very informative and relevant. The podcast truly helped me better reflect on my own practices on inclusivity.

With this being said, this fall I am presenting the use of sentence frames/stems to my staff as a way to support academic discussions in the classroom. I want to ensure that the way I present the material reflects cultural inclusivity and doesn’t promote the concept of a “right or wrong way of speaking,” but rather encourages “inclusive talk structures.” Can you provide some insight and/or guidance on how to do this effectively?

Thank you in advance!

Hi Sara, and thanks so much for listening! I’m so glad to hear the episode resonated with you. Sentence starters are a great way to scaffold oral language development in both monolingual and multilingual learners. Although they may seem artificial or forced at first, there are ways to ensure that they are being used in a culturally relevant or responsive way. Here are some things I recommend you share with your staff:

The section, MY STUDENTS NEED TO LEARN ENGLISH, AND FAST. WON’T CODE-SWITCHING SLOW DOWN THEIR PROGRESS? addresses a common concern among teachers who feel their students need to learn English as fast as possible, and typically, they will use sentence starters to help MLLs acquire English. One thing you can suggest to your teachers is that they can broaden the scope and impact of this strategy by making languages other than English available to students during discussions. In the next paragraph, I explain how to do that. The other section, GET THEM TALKING, refers to a variety of talk structures. Sentence starters and sentence frames are a great scaffold for students who are working in small groups or pairs because they’ll have more time and less pressure on them as they navigate the new ways of speaking.

As far as how to use them, if you want to make sentence starters accessible and easy to use, I would caution against presenting pre-written lists of sentence starters. Large amounts of text can be overwhelming and you may find that students rely on the same few phrases that they have memorized instead of actively choosing from the list. Instead, co-create some starters with your students, charting their suggestions while guiding them towards words or phrases you know will be especially useful for the lesson. This is a great opportunity to introduce content-knowledge vocabulary as well as bring in languages other than English to the mix. Next, model or have a student model how to use the starter and give the class an opportunity to practice, either through a turn & talk with a partner or a call-and-response as a group. Post a print version in a visible spot during the lesson and encourage students to support each other in using it as frequently as possible. Repeat this process in other lessons and grow your list organically. Students will take ownership of the process, be more motivated to use new terms, and not only will their vocabulary grow, they will share the vocabulary of their peers in addition to what you have to offer.

Another point of consideration is how to differentiate for students with varying aspects of language needs. Sentence starters can be modified to create sentence frames where parts of the sentence, not just the ending, are able to be completed by the student. For example, a starter would be: “I agree because ____” while a sentence frame looks like: “Jazz is _____ than classical because ____ .” You may find that sentence frames are more useful for helping students respond to specific questions while the starters are best for generating talk.

In general, tell them their planning will be guided by the abilities and interests of their students. The key to remember is that students should be active participants in the process. Hope this answers your question– and let me know if there’s anything else! Have a great school year!

Thank you so much for your thoughtful reply!

How does using WIDA scores fit into this discussion? Do we need to instruct and assess based on those for EL students?

My state is not affiliated with WIDA, so I can’t speak specifically to their approach, but language-based standards and the accompanying assessments are intended to guide teachers in supporting students’ language acquisition. Just as WIDA or English Language Proficiency (ELP) standards build proficiency in language skills and simultaneously support students in acquiring proficiency in content-area standards, linguistically inclusive pedagogy enhances (not competes with) the communication and academic goals we set for our students by developing self-esteem, socialization, criticality, and self-determination.

Hi Andrea! Current student teacher here, and I just wanted to say that I really appreciate your explicit connection of language to identity. I have personally done many identity webs, charts, etc., but I do not believe I have ever included my language in any of them, which I might now describe as “1L white English-speaker with a mid-western accent”.

Thank you for this thought-inspiring piece!

Hi Shelby Grace! I’m happy to hear that my post resonated with you. Language is an important part of our cultural identity, and I hope this helps inform your thinking about students as you move into the classroom. Best of luck!

I became ESOL endorsed through my regular teacher training program. It was a great idea, but the training really did not necessarily prepare me for the real world of teaching English learners. I am not the designated ESOL teacher in my school, but I often have ESOL students in my class. You have given me a lot of ideas to incorporate, and eased my mind about not being able to speak Spanish!

I have also noticed students who are bilingual and proficient English speakers will often speak for students who are early English learners. Is this something I should discourage?

Hi, this is a great question. It’s understandable to want students to speak for themselves, but at the same time, you don’t want to put anyone on the spot by asking them to say things before they’re ready. There’s no need attempt to limit conversation between students, but it does make sense to channel that helpfulness into productive support. What you can do is give early English learners an opportunity to express their ideas by either adding on or repeating someone else’s response. For example, if you ask a question, “What color was the cat?” and the early English learner responds in Spanish, a friend might jump in and translate. This is fine. Your next step would be to ask the first student to repeat the answer in a full English sentence, or maybe just name the color. Then, you can ask a follow-up question specifically for that student, telling their friend to let them try it on their own.

Remember, the important thing is that the early English learner feels supported, heard, and has an opportunity to speak in that moment. In fact, students often learn better from peers their own age, so I’d suggest that you continue to guide more proficient speakers to encourage their friends to speak up. Hopefully, as they get more comfortable, it will happen without your input.

How do you incorporate this with standardized testing and expectations of the world in general? That’s my real worry. I love how my students talk and write, but I’m afraid that they’ll be stifled by the ACT/SAT/employers who expect SE, etc.

Hi Abigail,

As I mentioned in my post, making space for linguistic diversity is not about rejecting Standardized English as a valid form of speaking and writing, but rather widening our definition of language to include dialects other than Standardized English. As teachers, we can make changes to our practice as well as advocate for more inclusive policies in the academic world. No students should have to limit their authentic selves in order to get good grades, go to college, get a job, or earn the respect of their peers.