Listen to the interview with Sarah Riggs Johnson:

Sponsored by Listenwise and Scholastic Scope

One September morning in a writing workshop class, Jack, a 5th grader, was telling me about a funny “small moment” he witnessed on an airplane. Apparently, two young 20-somethings sitting in front of him had started up an initial conversation and by the end of the flight, they were kissing.

“And I mean—a lot of kissing! It was sooo awkward!” he squealed.

Where most 5th graders were planning their narrative writing about the time they broke their arm/wrist/ankle or their game-winning shot/hit/goal, I thought Jack’s idea was so refreshing. After his detailed description of eavesdropping, I felt certain his piece would be funny and weird-in-a-good-way—a joy to read. I left him to write and went to help other students. When I returned, Jack’s writing teacher (my friend and colleague) stood beside his desk with a hand on her chin, looking perplexed. Jack had sat for 45 minutes with only this written on his page:

On tim on a plaen…

Jack’s accommodation plan said he had dyslexia and graphomotor difficulties, which was one reason I was in his writing workshop that morning: He was one of many students I had the privilege of working with as a learning specialist. Sometimes we would meet in a small group outside of class, and other times I would work with him in his regular 5th grade class. As a learning specialist, my role was to help Jack’s English/Language Arts (ELA) teacher figure out how to help him write. Her role was to help me figure out what skills to focus on with Jack during my intervention time with him. Over years of doing this work, I discovered some essential elements to improving students’ writing through this kind of collaborative practice between regular classroom writing teachers and learning specialists.

If you’re part of a similar partnership, you may find some of these helpful in your work as well.

Why Writing is Especially Challenging for Students with Learning Differences

Writing is an incredibly complex task. It involves the instant integration of several components—handwriting and letter formation (and later typing), spacing and formatting on the page, spelling, grammar, sentence formation, adding punctuation—all while holding your ideas, and some sort of organizational scheme for those ideas, in your memory. It’s a difficult enough task for most students, who aren’t reading as much as they once did due to our instant access to visual media. But it’s particularly challenging for people with language-based learning disabilities, who often continue to struggle with writing even in adulthood.

Students with learning differences often experience a more severe “cognitive bottleneck” first described by theorists who studied attention in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Some conventions of written language make it to the page while others…don’t quite make it. Did Jack know how to spell “one,” “time,” and “plane” in 5th grade? Yes, he did. He had years of multi-sensory phonics and reading intervention behind him. However, the other cognitive demands of the writing process caused his spelling to get caught in the bottleneck.

Other students with learning differences also struggle with writing. Students with ADHD sometimes struggle to organize language, keep track of their ideas, or explain with enough detail. Students with Autistic Spectrum Disorders often struggle to understand writing from the point of view of their readers.

Helping these students become proficient writers takes the synergy of a skilled language arts teacher and a skilled learning specialist. And that synergy can be enhanced if certain elements are in place.

Essential Elements of Effective ELA-Specialist Collaboration

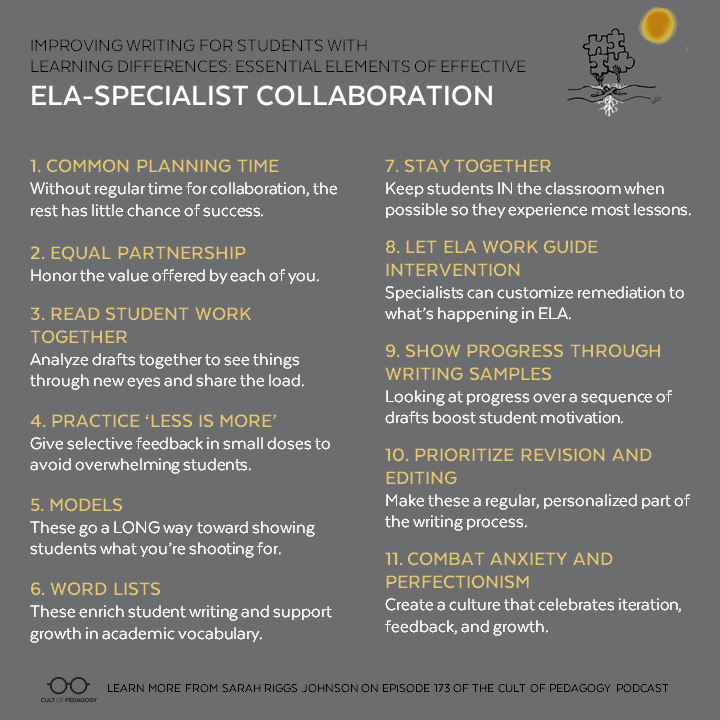

1. A Common Planning Time

The biggest impact a school leader can make in the quality of instruction for ALL learners is to give co-teachers common planning time. I was lucky to start my career as a special educator in a school where my division head handed me a blank schedule with two periods already filled in. It said, “Common planning time with the 5th and 6th-grade Humanities teams.” For 55 minutes once a week, three humanities teachers and myself gathered around the student work table in my office with coffee (lots of coffee), books, laptops, and a last-minute Post-It note agenda.

As a result of these meetings, reading and writing workshops were problem-solved, social studies lessons were well designed, student work was analyzed, student needs were met, and friendships and co-teaching relationships I will cherish forever were formed. The cast of characters changed over the years as teachers left and were hired, including myself, but the value stayed the same. More recently we’ve had to have these meetings as floating heads on a screen, but the value in sitting down together to talk about how we would teach has never wavered for me.

2. An Equal Partnership

Collaboration works best when the ELA teacher and the specialist work on equal playing fields. I like to think of it as a psychologist and a sociologist working together: One is focused more on how an individual is functioning; the other needs to be focused on the good of the group. Nobody is right and nobody is wrong. Sometimes our ideas will seem out of touch with each other’s roles, and that’s okay as long as we honor the value in each other. As a learning specialist, I am not an island in knowing what’s best for students, even students with learning differences. It works best when there is shared ownership; when we can see their growth as “our” shared goal!

One practical way to accomplish this goal is to rotate groups. There were times when I would work with the most talented writers in the class, giving the ELA teacher more time with our struggling writers. My colleague and I would always have lots to talk about afterwards, and the kids did not feel the stigma of being the only ones asked to work with the specialist.

Another way the specialist can reduce stigma is by taking part in some of the fun that happens with the class—help judge a competition, give feedback on a project, participate in a class celebration and connect with students other than the ones you are there to serve. Students will come to see you as just another one of their teachers, and as a resource for all.

3. Reading Student Work Together

Whenever possible, both teachers should analyze student drafts together to discuss the good, the bad, and the ugly of students’ writing. Doing this together will help you see different strengths and weaknesses in a piece, and the student will then learn to see these as well.

Sharing the writing load also means you can divide up written feedback on student drafts. By rotating which teacher gives feedback to which students, you give students the benefit of both sets of eyes and continue to establish an equal partnership with all students.

4. Practicing ‘Less is More’

With a task as complex as writing, all students—but especially those with learning differences—can experience cognitive overload. So it works best to tackle one chunk, one scene, one paragraph at a time.

When it comes to feedback, many students are overwhelmed by too many comments just as they used to be with too much red ink. I rely heavily on giving students genuine praise—for a descriptive adjective, a well-crafted phrase, an attempt to apply the lesson to their writing—and then I follow it up with one or two suggestions for revision. Psychologically, all students have to feel they have something to say; they have to feel positive about the effort they’re making, so very specific, authentic praise will earn you a lot of effort in return.

Another way to reduce the quantity of written feedback is to give some of it verbally, which allows for the levity and nuance that “Insert Comment” can’t achieve. In-person conferencing is ideal, but in the last 6 months, I’ve learned to record quick screencast videos explaining my feedback, highlighting sentences, and typing comments to illustrate different areas for improvement.

5. Use of Models

ELA teachers tend to read widely! One of the most effective things we can do together is figure out some interesting examples to use with our students who are struggling—the perfect opening paragraph, the perfect fight scene, an example of suspense building, describing the setting, the expert’s quotation being explained. If we have these at the ready, we can pull them to discuss and analyze with students. I also always recommend saving exceptional work (de-identified, of course) to use as models for the next year. For remote learning, I always have models or visuals pulled up as separate tabs and ready to be screenshared as needed.

6. Use of Word Lists

I have an entire library of word lists where students can look for the perfect word or phrase. I always end up lending these to the writing classroom. A more specific word for walked, blue, big, or sad can make an emerging writer feel like a poet. This is especially effective when working on writing poetry and descriptive writing, but it can also be used for older students writing analytical pieces as they struggle with transitional language and tying their points together. Why not have a list of templates at their disposal, i.e., “According to…”, “This demonstrates why…” etc.)?

The act of scanning the lists for just the right word or phrase improves the student’s ability to clarify meaning and see possibilities. The student with a learning difference is also sometimes not well-read and needs exposure to two things: (1) new ways to say things and (2) the nuanced difference in the meaning of certain words or expressions. I will often practice this act of list scanning with students… “Hmm, let’s try out some different words here and see if you can find one that makes you feel something… or seems like the perfect fit!”

7. Staying Together

Try not to remove a kid who struggles with writing from writing instruction. Students who struggle learn more than you think from their peers, even if their writing skill is not comparable. Instead of pulling students who struggle from the classroom during writing, work with the specialist to make the instruction more accessible and more enjoyable. Sometimes the specialist can arrange to physically or virtually be in the classroom working with students, and at other times he or she might “asynchronously” design a graphic organizer, outline, or checklist, or make a plan for integrating assistive technology like speech-to-text accessibility features or dictation apps for certain students.

8. Letting ELA Work Guide Intervention

Specialists can reinforce mini-lessons, genres, and concepts taught by the ELA teacher in the writing lesson—and add a touch of language remediation. If my students are working on persuasive essays in writing class, every sentence I have them analyze for word study or work on reading fluency will be from a persuasive writing sample and as closely aligned with their personal interests as I can plan for that week. This builds confidence and familiarity with the writing genre in addition to the skills I am targeting.

There is magic in teachers working together to reinforce the same knowledge and skills. I love it when a student I’m working with exclaims, “Wait a minute, we just talked about this in a writing workshop today!” Then, depending on the student, you can sarcastically feign shock “REALLY?” or just give them a knowing side-eye! We all need all the magic we can muster right now.

9. Showing Progress Through Writing Samples

Progress towards the achievement of IEP or SMART-style goals can be made visible through a timeline sequence of writing samples. I once taught a student who wrote with no punctuation. Even when this student re-read to add periods, he could not distinguish where a sentence began and ended. It was difficult for him to hear the natural pauses in speech; complex grammar concepts such as subject and predicate or even “being verbs” were difficult for him to grasp.

His teacher and I came up with a weekly routine that balanced getting his ideas on the page sans punctuation in writing class, and working on dictated sentences (from his own writing!) with me until his natural sense of pause and punctuation improved. We were able to demonstrate this progress by simply sequencing the drafts of his writing throughout the semester and showing him the changes over time. Working online, it is easy to annotate a student’s digital writing portfolio, pointing to their progress with certain skills. When you can show a student their own progress in this way, and have them reflect, it tends to increase their motivation tenfold.

10. Prioritizing Revision and Editing

Students with learning differences that impact writing often struggle with clarity and mechanics. Once students write to get their ideas on the page first, they can develop a multi-step process for what I call the R’s: re-read, revise, and sometimes I use the word revisit.

Ideally, each student would have their own checklist for this process, and it would be generated with and not for the student. For example, I might advise them to start by revisiting their punctuation/ sentence boundaries. Next, they could revisit their spelling. (For a student who doesn’t recognize their own disordered spelling, this can be even more scaffolded by the teacher putting a number of misspellings on the line and asking the student to find them.) The list would include each of the aspects we discussed through our mini-lessons for that particular genre of writing. Through this process, the ELA teacher and the specialist may have different suggestions for revision and improvement, and that’ll only make the writing better!

Another way to teach revision as a process is to have students re-visit their writing with each square of a single-point rubric, which can be especially valuable if generated by the class. Revisiting writing with a rubric (all the R’s!) can be fun to do in peer-revision stations, where peers are assigned a specific aspect of the rubric to give the writer feedback on.

Another tip: I often instruct students who struggle with sentence boundaries, to re-read their piece backward, from the last sentence to the first. This eliminates the memory of what they think they have said and lays bare the sentences as they were written. Students tend to go, “Oh yeah, this is definitely too long to be one sentence!”

11. Combatting Anxiety and Perfectionism

Some students struggle with writing because subconsciously, the fact that they cannot write on the level of the books that they love to read frustrates them (e.g., If I can’t sound like J.K. Rowling, I’m a failure, and so why even get started?). For a student with this mindset, I work with the ELA teacher to come up with very specific models. (See #5). And always, always show them the timeline of their drafts to reinforce progress (See #9). I also borrow a favorite phrase from my colleague, the ELA teacher: “No matter what kind of a writer you are, when you think you’re done, you’ve just begun!”

As we know, writing is an endless, limitless, boundless creative task. Students who are uncomfortable with this type of endeavor have to be taught some strategies to wade into it and find some comfort with themselves, with feedback, and with change.

These are the tenets of what helped Jack eventually write that narrative piece, one of the most original, giggle-inducing stories in his class. He needed the mini-lessons his ELA teacher taught about leads and dialogue, “juicy” details and setting the scene, creating a movie in the reader’s mind, etc. He also needed the language support, the remediation, the accommodation of some writing by dictation, and the editing and revision strategies taught by the specialist. He needed two writing teachers who were encouraging him to use and develop his comedic voice to write.

In addition to being good for the diverse young humans we serve, this type of healthy collaboration between educators is a game-changer for teaching practice. I have always found it helps me bring the art and the science together; it’s creative and innovative and validating. It can make you feel like you are on fire in your teaching again, especially if you’ve been teaching alone for a long time. As with all things teaching and learning, it’s not always neat or easy, but it is ultimately pretty dang rewarding.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

I am presently taking a course, “Teaching Reluctant Writers,” through John’s Hopkins. This podcast reinforced, reminded, reinvigorated.

Thank you

I agree that co-teachers should be given common planning time. People tend to forget that planning is essential for teachers. Otherwise, they could fall into a spot where they have nothing to teach or their students refuse to learn.