This page contains Amazon Affiliate and Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

Give me 5 minutes and you’ll have a new teaching strategy under your belt.

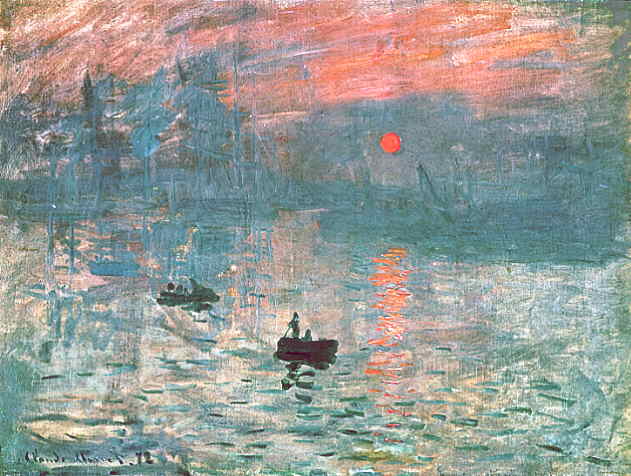

Suppose you’re an art teacher. This week, you want to introduce your students to Impressionism, the style of painting used by artists like Monet and Renoir. Now, you could just give them the name of the style and a definition, then show some examples.

OR!!!

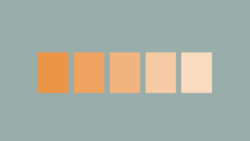

Using a strategy called Concept Attainment, you could reverse that order. Instead of providing any terminology or any kind of definition, you could simply tell students that you’re going to study a new style. To learn the style, you’ll show them paintings that use that style, and paintings that don’t — Yes and No examples. Their job will be to come up with a list of characteristics that they think define the style.

You begin with this first Yes example:

Then a No example:

Followed by this one, another Yes example:

Then another No:

As they study the examples, students work to develop a definition, or a list of characteristics common to all the Yes examples. Once they’ve done this, you give them more Yes examples to test and refine their list. Ultimately, students arrive at a thoughtfully crafted definition of Impressionism — one that will stick with them much longer than if you’d just given it to them to begin with.

For a more thorough example of how Concept Attainment works, I offer you this video demonstration:

The Research Behind the Strategy

I first learned this strategy in Silver, Strong, and Perini’s 2007 book, The Strategic Teacher: Selecting the Right Research-Based Strategy for Every Lesson (Amazon | Bookshop.org). In their chapter on Concept Attainment, the authors explain that the reason this strategy results in deep understanding is because it works with the way human beings instinctively learn. As we experience the world, we naturally organize things into categories based on common attributes. Concept Attainment is structured in the same way.

In their 2001 book, Classroom Instruction That Works, Marzano, Pickering and Pollock identified nine classroom practices that produced the most significant gains in student learning. This strategy uses two from that list: identifying similarities and differences (which was at the top of the list), and generating and testing hypotheses. (See the 2022 edition of the book on Amazon or Bookshop.org)

I like this strategy because it really involves students in their own learning. Instead of just delivering the information to them, you’re helping them discover it on their own. Also, it’s captivating — a mystery to solve! — which is far more likely to engage students than straightforward delivery of information. Finally, it’s a pretty easy switch to make from what you’re already doing: definition-then-examples becomes examples-then-definition, then maybe a little lecture just to tighten things up.

Share Your Experience

Concept Attainment could be used in just about any subject area and at any grade level. I could see it in corporate training, in coaching, even when teaching a preschooler how to wash his hands (“We’re going to come up with some rules for hand washing. Watch these five kids wash their hands. These three are doing it correctly, these two are not. What do you think the rules are?”)

If you have used the strategy and have more information, variations, tips on doing it well, or even a correction to how I’m presenting it here, please tell us about it in the comments section below.

Hope this adds something new and different to your repertoire! ♦

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Hey! I didn’t know there was a name for that strategy. Excellent!

Samesies! It’s basically the strategy I’ve been perfecting (not that any strategy can ever be truly perfected) over the eight years I have been teaching technology subjects. Exciting stuff!

This is great to put a name to a strategy that I have been using. I knew instinctively that if my students figured out what connected the [blank] together and could come up with a definition/pattern then they would remember it much better than if I just wrote on the board here is the way these verbs work or the definition of this concept, etc. I love seeing things click for them. It is a much more exciting way to learn for both them and me!

That is really a great idea! I can see how it could apply to any type of learning and will definitely share with my colleagues. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks! What industry do you work in?

I work in learning and development for a medical device company. You have NO idea how much training and on-going education is required and, quite frankly, nobody has a degree in education around here so all our efforts are either hit or miss. Trying to educate myself so we have more hits than misses! Keep up the great work. Very inspiring!

Does this work in adult learning as well? Say I show employees an example of a well-written permit, versus a poorly-written permit, one with not much information. Do you think this would result in them learning to write good permits?

I think it would work beautifully with adult learners. What’s nice about this strategy is that there’s nothing childish about it. And yes on the permit writing. With any kind of writing, this would work really well. Show a few examples that are done well and a few that have some good qualities but not enough, and have participants come up with a list of qualities that describe all the good ones. It’s funny, because writing teachers so often give students rubrics before a writing assignment to describe all the characteristics of a well-written piece. Now I’m thinking students should study models of pieces that are written well and try to figure out what constitutes a good paper. Anyway, yes on the permits. (Also, because I know that you work in the safety industry, I will also add that using examples and non-examples to teach different safety principles would also be a great way to get stuff across!)

I do this all the time in Eng 101 in college, so yes it works beautifully with teaching writing. What is the genre? What are the genre expectations? Which of these samples meets audience’s expectations better and why?

This strategy sounds quite interesting! I’m a middle school English teacher and I would appreciate if you could give some ideas on how to effectively use this for middle school. Especially with poetry and prose and critical thinking skills.

Many thanks

Bindu

Bindu, I see that it’s been quite a while since you posed this request. So sorry about that!

If you haven’t already, I encourage you to take a few minutes to watch the video demonstration embedded in this post. It breaks down how to use the strategy specifically with ELA content, in a way that would be appropriate for middle school students. All you would need to do is swap the figurative language content for poetry and prose!

Other educators have also shared their ideas and experiences for using this strategy if you read through some of the other comments. I hope this is helpful!

I use Concept Attainment when teaching Social Emotional Learning to my students (although I didn’t know the strategy had a name). The students are 100% engaged and take ownership of the new SEL strategies because (they think) it’s their idea and their rules. BTW, love your stuff. Keep it coming!

I’ll try this as soon as I get back to class after Thanksgiving Break; it’s not a new strategy for me, but it’s one I tossed to the side in more recent years. I’ve found this strategy to work really well with English Language Learners.

Thanks for the reminder!

I am ELL teacher and this is awesome for ells. I love getting away from teacher telling students listening. Thanks!

This is exactly the same idea as “supervised learning” in machine learning and artificial intelligence. In that setting, you feed examples and non-examples to an algorithm to train it on what is a “yes” or a “no” example, so that it can make these determinations itself in the future.

Thanks for that clear example in your videos! This is one of the strategies I’ve showed student teachers but the video makes it much clearer. This strategy also appears in the book Beyond Monet by Barrie Bennett and Carol Rolheiser….which is basically a compendium of excellent teaching strategies.

Thanks! I’m excited to try this. I was trained NEVER to use false examples (a “NO” in this context) because they supposedly lead to students internalizing incorrect information. This was in the context of foreign language teaching. I always felt that there was a place for them though–thanks for giving me the idea to revisit.

I love this. I visited your site searching for help because I’m having to write a lesson plan using concept attainment for grad class, and I was totally lost. You explain it beautifully, and I definitely plan on implementing it in my own classroom, not just for this assignment! 😉 Thanks so much! Great video!

how do I use (concept attainment strategy ) for creativ in design? I’m a industerial designer.l need a metod for discover when the complex problem is there.

Hi Mostafa,

Can you give me an example of the kind of concept you’d be trying to teach? I think concept attainment would be perfect for teaching design. Regardless of the concept, you show “yes” examples of the concept, then “no” examples, until students begin to be able to define the concept for themselves. For something like design, which can sometimes be hard to pin down, this method would result in much deeper understanding and transferability of the concepts.

Thanks for the reminder. I can see this being very helpful teaching the distinction between monomers and polymers that my students are working through right now in Food Science.

This is one of my favorite instructional models. I first used it after reading Models of Teaching by Joyce and Weil.

I LOVE this concept! It reminds me of a strategy I use in my reading class – Frequent Contact. Students are given a list of vocabulary words from the story (in my case, from Crispin, by Avi) and have to group the words into categories. I also can differentiate and give some of my students the names of the categories with the words. Either way, it generates great partner and class discussion because there isn’t one clear answer. The categories that students come up with are always so creative, and open my eyes to new perspectives. Frequent Contact comes from one of my favorite books – Inside Words, by Janet Allen. Thank you so much for sharing – can’t wait to use this one in the classroom!

Thanks for sharing, Wendy! I’m looking forward to checking out Inside Words!

I use Inside Words a lot! I hope you enjoy it as much as I do 🙂

I learned about Concept Attainment in my student teaching at UC Santa Barbara in 1987 (thank you Ron Kok!) and while no longer in education, used it with training customer service reps at Patagonia for how to classify and get the key data needed for website issues from customers just a few years ago. Concept Attainment is one very powerful strategy! Glad to see it getting attention and details here — your website is one of my favorites.

A wonderful colleague shared a “mystery lesson” on Google Slides to use for teaching unit fractions. I was nervous that students would not understand, but the way they caught on and developed their own definition blew me away! I had no idea there was a name for it and I LOVE that I know have some research and literature to back up the teaching practice.

I also learned this strategy from Bruce Joyce’s “Models of Teaching.” It is an old text, but I learned so much from implementing Joyce’s coaching model for learning strategies and shared (and modeled) the most powerful of them with my education students at the university level.

The part I like best about concept attainment is that you can also turn the set of yes and no examples and use it in another powerful strategy by having the students categorize them into their own groups and share why they put them where they did. I sometimes used this prior to a concept attainment so that they started talking about the characteristics of the items in a set before I would lead them to a specific example. In your example, you noted how students quickly utilized names for specific “pieces” that were in the set (ie. Metaphors and similies).

One of my favorite lessons for this has students look at a very large set of cookie recipes. I ask them to focus on what they do after the batter or dough is mixed prior to putting them in the oven. I usually give them the number of groups to put the recipes in. Their conversations are rich, and they look at a lot more than just what I ask them to focus on AND they actually know why and how cookies are categorized into specific groups after that. They think about how they might change a recipe in order to make a specific type, they know how to tell if they made a mistake if the dough is too thin to drop or roll, etc.

I’ll never forget the time one of my university students told me her head hurt after my class because she thought so hard — that’s the best compliment that our students can give us!

This strategy is awesome. I have used it a lot in my Science classes but did not know it had an official name. Thank you so much for sharing. You are such an inspiration.

This is great to hear, Kendra! I’ll make sure Jenn knows.