Listen to my interview with John Stevens and Matt Vaudrey (transcript).

If you’ve been looking for a boost of inspiration lately, something to help you engage students deeply and make your teaching fun again, then I have just the book for you: The Classroom Chef, by Matt Vaudrey and John Stevens.

Here’s the premise: If we want our lessons to have a long-lasting impact on our students, if we want to make our content really relevant, we need to design instruction the way a chef orchestrates a good meal, from appetizer all the way to dessert. And like any accomplished chef, we will only get really good at it if we take risks, experiment, and are willing to fall flat on our faces.

In the book, Stevens and Vaudrey show us how they learned to do this in their math classes. Although the examples are all from math, and math teachers are going to absolutely LOVE this book, it’s easy to imagine how the same kinds of lessons could be prepared in any subject area. Non-math teachers who skip this book will really be missing something special.

The Classroom Chef: Sharpen Your Lessons,

Season Your Classes, Make Math Meaningful

by John Stevens & Matt Vaudrey

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. (What are they?)

The Big Takeaways

Here’s a run-down of some of the book’s best ideas.

Avoid Processed Food

This was my biggest a-ha from the book. Too many teachers treat their instruction the way a college student approaches food, going for the easy, pre-packaged, processed stuff—in other words, worksheet and curricula straight from the textbook companies—rather than preparing lessons with more thought.

“We weren’t happy with processed-food curriculum,” the authors write. “Outdated pre-printed modules for the students, a pacing guide to follow, and an entire department doing the same thing. And, from our observations of the students who had learned to hate math prior to arriving in our classrooms, it was clear a processed food math class wasn’t going to cut it. Somewhere along the line, we decided to learn how to cook math and serve it up like a fine meal.”

Stevens and Vaudrey concede that preparing thoughtful lessons takes a lot more effort, and some of your attempts will bomb in the same way new recipes can fall flat. Still, the level of student engagement and learning you’ll get from these efforts will ultimately pay off.

The Appetizers Set the Stage

Although this is not a new concept, and I have written about the value of good anticipatory sets before, Stevens and Vaudrey’s approach to “appetizers” makes them a truly integral part of the lesson, a way to hook students into the day’s learning that goes beyond merely getting their attention.

In our interview, Vaudrey explained it this way: “Instead of saying, ‘Hey, guys. Let’s start with notes. I’ll give you the instruction first, and then we’ll interact with something,’ the appetizer says, ‘Hey, here’s this idea that gets students curious and interesting and hungry for the instruction.’ Now they want what you’re selling. Now they’re hungry for what you’re providing, and your instruction now is filling a need for them, filling a hunger for them.”

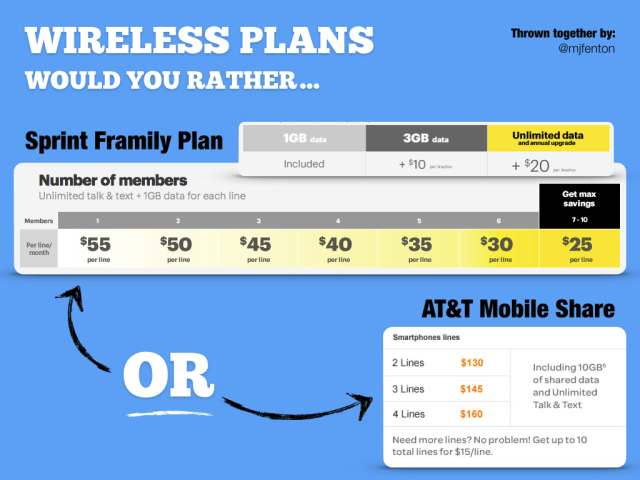

In the book, the authors show us how to look at the day’s learning standard and figure out how to pull students into it—using a meaningful argument, question, or challenge—without ever referring to the standard itself. Here’s an example of the kind of appetizer they might use, from Stevens’ Would You Rather? math website:

Hey!! This is not an ad. It’s a math lesson!

In this appetizer, students need to pick a wireless plan. Making this decision requires choosing which math strategy to use, then applying it in order to justify their choice. By arguing for their particular preference, students are engaging deeply with math in a way that applies directly to a situation they might actually find themselves in someday.

Serve High-Quality Entrées

The entrée is the real substance of the meal: the main lesson. This is where the learning goes more in-depth, where students work with the standard you intend to teach them…except they may not know what that standard is for a while. That’s because rather than simply providing direct instruction on the content, a good entrée delivers it in a context students are actually interested in. “We would much rather students have a meaningful experience in class than restate a standard,” the authors write.

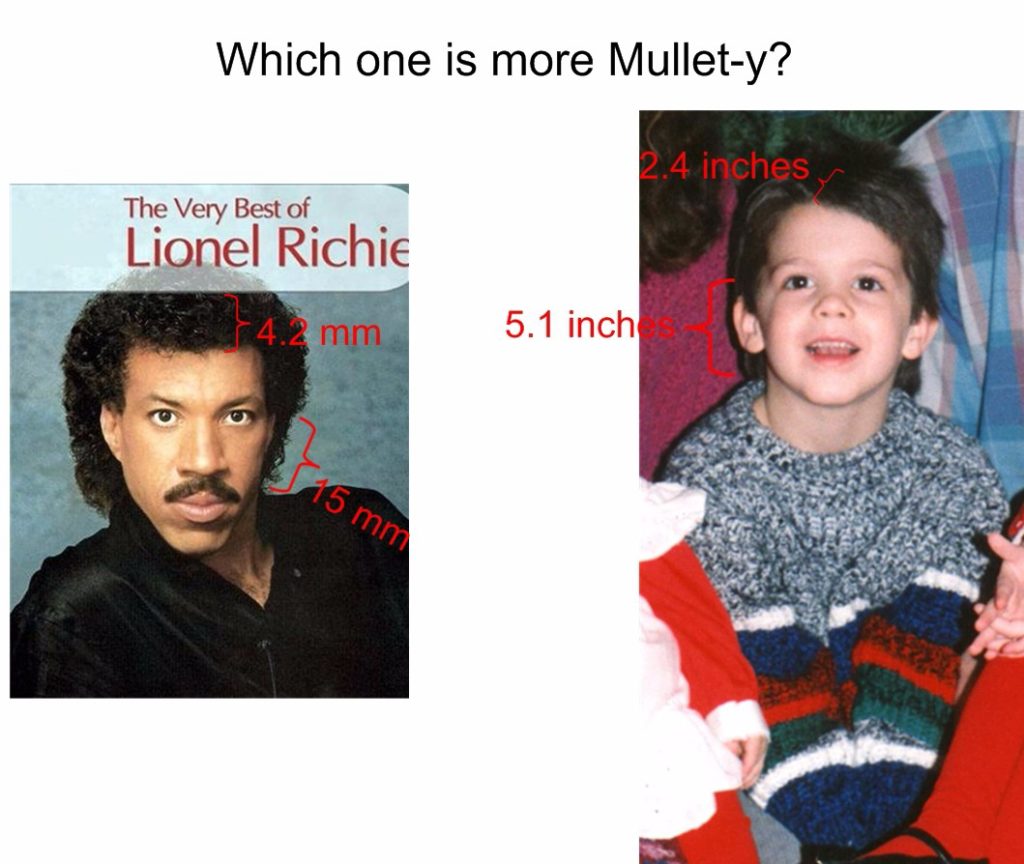

One such entrée is the Mullet Ratios lesson, where students begin by looking at examples of mullets and deciding which haircut is more “mullet-y.”

Stevens and Vaudrey walk us through lessons like this one and several others, like Barbie Zipline, Big Shark, and the lesson where students build a scale model of the Twin Towers to honor the memory of the September 11th attacks. By reading about each of these lessons and the thought process that led each of the authors to develop and teach it, readers will be able to apply the same thinking to their own content and prepare delicious, satisfying entrées of their own.

Treat Assessment Like a Dessert Cart

Assessment typically comes at the end, like a dessert. But what if a restaurant only offered one option for dessert? This is standard practice in schools: Most teachers give every student the same assessment. Even if we switch to a more project-based, performance type of assessment, we often assign the exact same one to every student. And why is that? “To be blunt,” the authors say, “it’s easier—easier for the teacher to create and monitor, easier to grade, and easier for kids to prepare for. Or so we think.”

The problem with the one-size-fits-all assessment is that it doesn’t do a very good job of assessing, and it also doesn’t fit all students. If we assign some kind of poster, where students are graded on the standard AND on things like creativity and presentation, we have two problems: (1) the grade doesn’t necessarily measure standard mastery, and (2) any student who’s not great with poster-making will automatically be at a disadvantage, even though poster-making isn’t the skill being measured.

Instead, teachers could allow students to choose their own assessment, to let them decide exactly how they will prove their mastery of a given standard. Doing this allows students to work in whatever medium or context suits their interests and talents while also showing what they know. The first time Stevens tried this, where students had to demonstrate their understanding of triangle congruence theorems, he got art projects, music videos, comic strips, blog posts, even a mock-up of an Internet dating site. “Students’ finished projects exceeded all expectations,” he writes, “[but] quality wasn’t the goal of this project. The real value was students demonstrating their knowledge in a way that was comfortable and effective for them.”

Solicit Reviews

A restaurant patron can review their experience instantly by going to sites like Yelp. Once these are written, the restaurant owners can read the reviews and make improvements accordingly. We should give our students that same opportunity by seeking their feedback. Stevens and Vaudrey share their system for having students complete a Teacher Report Card to give feedback, and what they do with the information once they’ve gotten it.

Teachers Worth Hanging Out With

Even if you get nothing else from this book (which would be impossible), reading Classroom Chef will be the equivalent of hanging out with two teachers who really have their heads on straight about teaching. Both Vaudrey and Stevens are painfully honest about their failures, excited to try new things, open to feedback and criticism, and always willing to geek out on teacher talk. For teachers who happen to work in schools where these kinds of people are hard to find, reading this book will give you the role models and kindred spirits you need to grow as a true master of the craft. ♦

Matt Vaudrey blogs at mrvaudrey.com.

You can find him on Twitter at @MrVaudrey and at classroomchef.com.

John Stevens blogs at fishing4tech.com,

maintains the Would You Rather…? math site,

and delivers a weekly parent newsletter on math at Table Talk Math.

Find him on Twitter at @Jstevens009 and at classroomchef.com.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll also get access to my members-only library of free resources, including my e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, which has helped thousands of teachers spend less time grading!

Amazon Affiliate Links: The links to Amazon in this post are Amazon Affiliate links, which means if you make a purchase after going to Amazon through them, I get a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for your support!

I LOVE food metaphors! Definitely on my “to read soon” list!! Thanks for sharing! 🙂

You’re welcome, Isabella!!

p.s. I love food metaphors, too!

This was good material. I want to grow as an effictive teacher, and be more engaging wiht my students. Question: if your students work well during the class period, do you give them free time at the end of it?

Hi James! Kids definitely need free time to explore their interests and engage is discovery, practice social skills through play, engage in a brain break, etc.; however, I would avoid setting up “free time” as a kind of reward, especially if it’s just for some of the kids. Instead, try scheduling much-needed free time for the whole class and be sure to set up expectations for how that time can be used. Here’s an article that might give you some ideas – check it out and see what you think. Hope this helps.

This concept of treating math education like a master chef is ingenious! I started to think about what my lessons have been like during my practicum in the school year, and during my previous summers teaching in a lower socioeconomic neighborhood. I’ve definitely been treating math as processed food many times because I want to follow what the textbook says, and try not to stray away from it. However, there is so much to math that can be expanded upon, even from a textbook. The example of using whose hair is more mullet-y is a great way of teaching ratios, and it allows students to see something so silly being used in math.

Also, a question regarding feedback: What are some of the ways you receive feedback from students after an assessment(s)? I’m curious because of the edTPA that I will be doing in the spring semester, and it would be great to know creative ideas for feedback.

Hey Andrew,

Matt and John give students a questionnaire a few times a year, but you’re specifically mentioning after an assessment. So are you talking about getting feedback about that specific task/assessment?

I listened to this podcast in the Fall and loved the idea of Choose Your Own Assessment! So I went off and created an assessment for my 7th grade Social Studies “Creativity” unit using this concept. It was a huge success. I created a video showcasing this approach and some of my students results. Highly recommended. Thanks again!

https://youtu.be/R4nv52x6zwo

I would love to hear more about adopting this for other content.

Hey Tammy,

Sometimes it can be hard visualizing how a strategy might work in a different content area, but I think if you look at the big picture, you’ll be fine. The main thing is to avoid these pre-made curriculum-type lessons. If you haven’t already, take a look at the post about Backward Design. This approach to lesson design works well with the article. Essentially, start by planning how you’ll assess students. It doesn’t have to be a test. It can be any kind of project, illustration, piece of writing, etc. Then decide on your anticipatory set (see link in post) and a main lesson that engages kids on a deeper level. Off the top of my head, one example might be this: if the standard is to understand friction and how different surfaces impact movement, I would come up with some ways kids could show understanding in the end. My anticipatory set might be a personal story of what happened when I had a hard time backing out of my driveway – a snowy icy uphill battle. The main part of the lesson could be for kids to visit various stations where they explore the movement of an object using different surfaces and slopes. This is a general example, but hopefully it gives you another way of looking at things.