Listen to the interview with Jane Currell (transcript):

Sponsored by Listenwise and National Geographic Education

I opened the envelope, unfolded the letter inside and began to read to my class: “Dear Residents of Alchemy Island, I am writing to inform you that a decision has been made to sell the east of our island to a large development company. They plan to use the land to build a vast new resort for people to come on holiday here. It will provide a lot of jobs for people living on the island as well as countless other economic benefits. Part of the Enchanted Forest will be cut down to provide adequate space for this state-of-the-art complex…”

This was a unit of work I initiated early on in the academic year with my new class of 9- and 10-year-olds. To be honest, it felt risky at the time because I was still getting to know them and was in a new teaching role in a new city. I wanted to try it in order to test out a pedagogy that would allow for collaboration and choice.

We had been learning about the fictional “Alchemy Island” for three weeks. We’d used geographical skills to navigate our way around it and science skills to analyze the properties of materials found on the island. The class had already completed some creative writing assignments, responding to fictitious themes relating to the island. Next, I wanted to include a writing unit that would enable us to break out of sitting in rows and work in genre-focused groups.

Alchemy Island had an area of forest. I decided this would be our focus and that they would write persuasively to stop the deforestation of the island. This would enable us to incorporate some critical thinking around the issue of the environment and learn how to write persuasively through lots of different formats.

A few days into the unit, I looked around the classroom and found myself in a rare moment of harmony where everyone was working collaboratively and appeared to be on task. My students were sitting in groups of different sizes from two’s to five’s, some with TA support, as they got to work on their writing drafts. My role had shifted; no longer ‘sage on the stage,’ I could be the ‘guide on the side’ and I began to go from group to group checking in on what they were doing, giving encouragement, asking questions to redirect learning, and supporting with writing models where necessary.

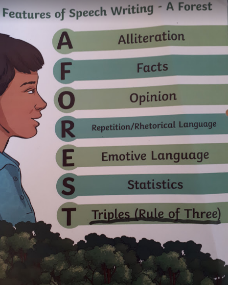

I paused by one pair of students who were writing a speech. They were using an anchor chart to prompt ideas and had already integrated some good speech writing techniques into their writing. “What’s the rule of 3’s?” I asked. They explained that you repeat a phrase three times at the start of three sentences in a row to add emphasis. They showed me their example; I was so impressed.

Putting students to work on a campaign—whether it be fictional or real—is a powerful way to get students writing persuasively. If designed carefully, campaign projects can be highly engaging, collaborative, authentic experiences, and they can work with a lot of different subject areas. They also create some great rapport as a class through the shared experience.

Let’s look at how they work.

Why Campaign Units Work So Well

Campaigns are a great way to get students engaged in social justice issues and powerful writing because:

- They relate to real-life situations and problems, which students are always drawn to and find easy to engage with.

- You can integrate critical pedagogy, posing questions such as Is this fair?, Is there equality?, or Who has the power in this situation? in order to both inform and prompt critical consciousness.

- Students can learn about the idea of using their voice and how we can do that in society when we want to see change. It gives them a practice run in a safe environment and prepares them for any social action they may want to get involved in outside of school.

- They provide an opportunity for collaborative learning. Whilst working on their own piece of writing, each student can deepen their learning by discussing and sharing ideas in a group. As they practice model sentences they can listen to each other, give feedback, and inspire one another.

- You can differentiate easily. Mixed-ability groups mean that students who lack some content knowledge or communication skills can learn from the talk of the more advanced students. Scaffolding or adult support can also be provided where needed.

- They enable students to practice a range of writing styles and genres, then showcase them to each other, thereby giving all students more exposure to different ways of persuading.

Doing Your Own Campaigns Unit

The following steps are a guide for how to go about planning and implementing a campaign for a class of your own:

Step 1: Look at the topics or themes coming up for the term with a critical lens.

Where is there a natural fit for a social justice campaign? For example, can you see an issue related to climate, gender, ability, poverty, or race that students could get behind for a campaign? Draw up a list and connect it to writing activities that could be taught through it.

Step 2: Clarify the campaign focus or put a short list to the class, discuss it, and then vote on an issue to campaign on.

Providing choice makes learning very meaningful for students because they have been part of the decision process; they can follow their own curiosity and focus on something they are passionate about. Although this time I had decided on the theme—which worked well for me in my first implementation of a campaign unit—providing choice about the cause to campaign on could be even more motivating. On evaluating the impact on their writing once my unit was complete, I felt that allowing students to choose their own writing genre and pairing it with a topical theme had been powerful.

Step 3: Pin down the resources you will need to inspire and support your students in their learning, especially to ensure that they grasp what a campaign is.

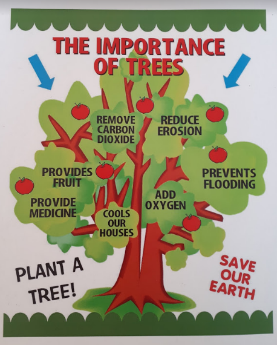

Once the theme was introduced by reading out my fictitious letter, we discussed our initial reactions to the news and began to work on our pre-writing. For this we watched clips about deforestation in the Amazon jungle and discussed the impact of it. We analyzed a poster about the many positive uses of trees and created a word bank around the environmental issue of deforestation. I showed the class clips of recent climate change campaigns and demonstrations in our locality to introduce the concept of campaigning. We began to grasp what a campaign is and that any age group can take part.

Step 4: Identify the types of writing your students will be developing and practicing during the campaign and prepare resources for these.

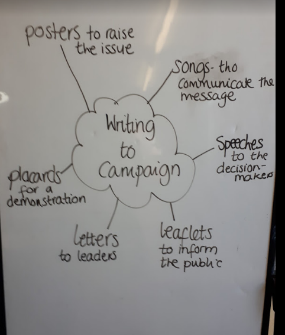

We came up with our list as a class: What kinds of writing could we use to persuade people not to cut the trees down? Or to inform others who might also want to join the campaign? Or to raise awareness of the issue to the Islanders themselves? Ideas included songs, letters, placards, posters, interviews, speeches, and information leaflets.

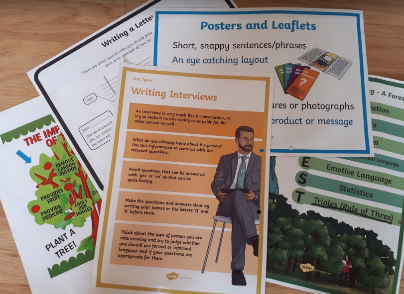

To support students in their writing, checklists and anchor charts were provided to focus them on what to include in the genre of writing they were working on. We also looked at models of persuasive writing texts and word mats and practiced using persuasive language in draft writing. With each group of students, there is also the opportunity to model the type of writing required by demonstrating model sentences and having them practice their own versions. For example, if they were writing a speech, then modelling the introduction to them helped them get the tone of a speech and get them started.

Step 5: Decide what size groups you want and how to manage the logistics of working in groups.

Once the cause is clear to students, options for writing have been provided, and resources to support are in place, students need to choose which type of writing they want to work on. Would they like to communicate their message on a placard to use at a demonstration? Would they like to interview the developers and see if they could persuade them to change their minds? Would they like to write a speech, create posters to raise awareness, or write letters to the Alchemy Island leaders to ask them to stop what was happening?

Each student made a choice and they then moved to sit in a group with those that had made the same choice. I limited groups to 5 and once a group was full it was capped. Those that were still deciding had to take that into consideration. For the students who struggled to decide what to work on, I added them to the smallest groups, where I felt the genre would work well for them or where mixed-ability groups would be enhanced.

Step 6: Plan the progression of lessons over your specific time frame so that you have an aim for each lesson. Out of these you can also pin down your learning objectives for your students.

For example, a progression might be that in the first lesson, you aim to discuss and vote on 3 issues in order to identify a focus for a campaign. In the second you might create a word bank of keywords around the issue from a range of sources. The next day, you introduce new vocabulary for persuasive writing and practice it. In my progression, we worked through a writing process of pre-writing, drafting, editing (with teacher and peer feedback), revising and then publishing. This provided a framework for the writing process and a structure for the progression of lessons.

Step 7: Identify and plan for any specific differentiation or support you will need to have in place for some students.

I found it helpful to have strategically placed Teaching Assistants where some group dynamics were difficult or where students would need support. I planned my sessions when I knew I could have the most adult helpers available. This enabled everyone to be productive.

Step 8: Implement your plan, adapting as you go and providing opportunities for groups and individuals to share their process and learning with the rest of the class at regular intervals.

At several points in each lesson, students read out extracts from their drafted work so that we could listen to and learn from each other. This enabled students to “catch” vocabulary from one another and for those struggling to use persuasive language to hear it and perhaps then be able to implement it themselves. They really enjoy sharing their work and it provided an extra moment in which to give feedback.

Step 9: Present and celebrate the completion of the unit and all that you have learned.

Each group presented their work to the rest of the class. We had a class photo with placards held high and then their work was presented on a display in a corridor for others to see. Some sort of conclusion like this creates a very positive class dynamic and they always relish the opportunity to share their work with each other.

A Priceless Experience

I learned so much from teaching a campaign unit. Afterwards, I was really pleased that my students could, with some support, manage more freedom and choice in their learning and I knew, therefore, that I could integrate pedagogy which promotes collaboration into more of my lessons.

When I run a campaign writing unit again, I would see if I could link our campaign to some authentic social action; for example, posting letters to a similar situation where development would create deforestation, or joining in with a real demonstration in which children were involved. I would also look for a wider audience by doing a class assembly on it or organizing a march around the school for other classes to hear about it.

Seeing my students so highly engaged over several lessons during this unit confirmed to me that choice—as research shows—really does motivate. Furthermore, sitting in groups with people they might otherwise not work with, being able to talk and discuss the task, debating the issue of deforestation and its impact on our planet, may have made their learning more meaningful as well as memorable.

I also discovered that when you provide a shared experience like this, it’s a bit like going on a trip: it builds cohesion and rapport among you and creates class identity, which was just what we needed at the start of the journey of learning we were taking together at the beginning of the academic year.

I enjoyed it enormously when, five months later, I was asking an open question in a writing lesson and heard a voice pipe up: “Could we do a campaign?” ♦

You can find more of Jane Currell’s writing at Passion for Pedagogy.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Thanks for sharing this compelling story and strategy. I’m curious about a couple of things. The opening letter mentions that the development would have economic benefits and would involve cutting down some forest. Then you state that you made the decision that students “would write persuasively to stop the deforestation of the island.” Additionally, when you describe your process in Step 3, it sounds like you and your students only explored the deforestation side of the issue. Is that right? Did any of the students decide the resort on the island was a good idea? How important was it that the whole class agree on the issue?

Hi Emma,

We’ve reached out to Jane and hopefully, when she has a moment, she’ll be able to help you out.

Hi Emma,

Once the letter was shared there was a unanimous response about wanting to stop the deforestation but I had angled it that way! An interesting alternative would be to have the opposing views, for and against, and have them write their arguments form both perspectives, have a debate or do role play.

Jane

I really enjoyed this podcast topic and am inspired to create a similar experience for a group of students. I am keen to find more information about Alchemy Island itself in order to set up the content for the unit. I checked the guest’s blog but could not find a blog post about this project. I wonder if there is another area that any information about this project might be posted or shared? Thanks for any guidance!

Hi Alana,

Jane teaches in the UK and from what I can tell, Alchemy Island is a project that is part of a licensed curriculum. My suggestion is to try planning your own campaign following the steps that Jane shares in the podcast as well as the post.

Hi Alana,

The Alchemy Island theme comes from a curriculum resource published by a company called Cornerstones. It provides planning and resources for themed units. Our school subscribed so there is a cost but you may be able to find out more about Alchemy Island online by going to the cornerstones website: cornerstoneseducation.co.uk. Hope that is of help. Jane

Hi Jane,

I am intrigued at your approach to developing this experiential learning opportunity for your students and I’m very interested if you have had the opportunity to start planning a project in which students are engaged in a campaign that is not fictitious.

Over the past three years, my Leadership students have been using design thinking as their problem solving methodology to solve real world challenges faced by non-profit organizations that operate in marginalized communities. I see a great deal of overlap in our programs in that the students work in collaborative groups to solve a social issue. They also are given choice, and I agree this greatly helps with student motivation as does their opportunity to create a final presentation during which they share their approach, challenges, prototypes, and final solution. Students keep reflection journals throughout the course and submit a final reflection at the end, but I’m wondering if you have any suggestions for other forms of reflection as this can become stale and yet it is such an important component of the experiential learning cycle. Any suggestions?

Thank you again for a very inspirational post.

Richard