Listen to my interview with Lisa Brooks (transcript):

Sponsored by Pixton and ViewSonic

When I was a “regular” classroom teacher, my knowledge of specific learning disabilities was limited at best. My teacher prep program required one course in special education; it was very broad, very general, and I barely remembered anything I learned in it. This means I was woefully ill-equipped to support the students in my room with special needs—those who arrived with a formal diagnosis and those who didn’t. I mean I literally knew nothing. No special strategies. No alternative methods of instruction. My plan was to just do whatever the IEP told me to do, which mostly involved shortening assignments for those students, giving them extra time, or occasionally reading things out loud to them. I didn’t really get why these things were helpful, and I did them with limited success.

So that’s the big problem: If my experience matches those of other teachers, and a 2019 report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities says it does, then a whole lot of students are spending a whole lot of time in classrooms with teachers who have only the faintest idea of how to support them. Yes, of course every school has special ed teachers, but if students with special needs are spending more and more time in mainstream classrooms, we can’t ask the special ed teachers to be the only ones doing this work. It’s time for the rest of us to step up our game.

And a good place to start is with dyslexia.

The International Dyslexia Association estimates that as many as 15 to 20 percent of the population as a whole has some symptoms of dyslexia. This is a much higher number than I would ever have guessed, and it means that anyone who has been teaching for any length of time has probably taught at least a few students who have dyslexia, whether we knew it or not.

To learn more about dyslexia, I talked with special educator Lisa Brooks, who currently serves as Principal Director of the Commonwealth Learning Center’s Professional Training Institute in Massachusetts, a nonprofit whose programs are designed to help teachers and specialists meet the needs of students who require systematic and multisensory learning approaches. In our podcast interview, Lisa dispelled some of the most common myths about dyslexia, shared some traits teachers can look for that might indicate dyslexia in our students, and talked about some things teachers can do inside and outside of the classroom to support these students and help them be more successful.

Myths About Dyslexia

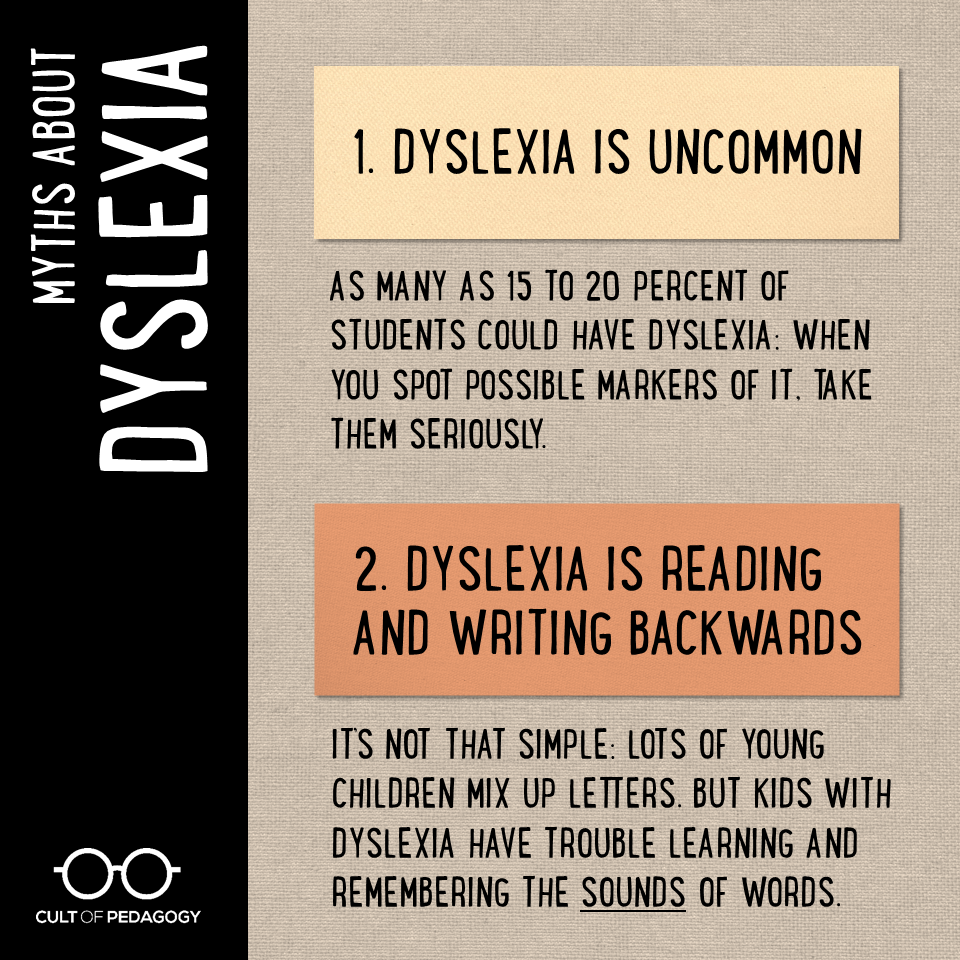

Dyslexia is Uncommon

Although some educators, myself included, don’t think of dyslexia as a high-frequency learning difference, “in fact it occurs in at least 15 percent of the population,” Brooks says. With that in mind, she says, “if you have 20 students in your class, probably three of them have markers of dyslexia.”

Underestimating the prevalence of dyslexia can result in students not getting the kind of early intervention that could make a big difference. Teachers may dismiss reading and writing difficulties as attention problems or the student not being developmentally ready for certain tasks, so the diagnosis is missed or delayed.

Dyslexia is Reading or Writing Backwards

“Most children when they’re very young write letters backwards, and that is considered appropriate for 4-, 5-, 6-year-olds,” Brooks says. “But dyslexia is not writing backwards. It’s really a difficulty in the phonological component of language, and that means children have difficulty with the sounds in words. We don’t want to just say, oh, my 5-year-old is writing upside down m and w. Does that mean he has dyslexia? There’s a lot more to it than that.”

Traits that May Indicate Dyslexia

If non-special ed teachers know the markers that may indicate dyslexia in a child, we may be quicker to refer them for testing. This, in turn, can get them the interventions they need, and when it comes to interventions for dyslexia, earlier is definitely better: A recent study showed that interventions in first and second grade made twice as much of an impact as those delivered in third grade.

Here are some things to look for:

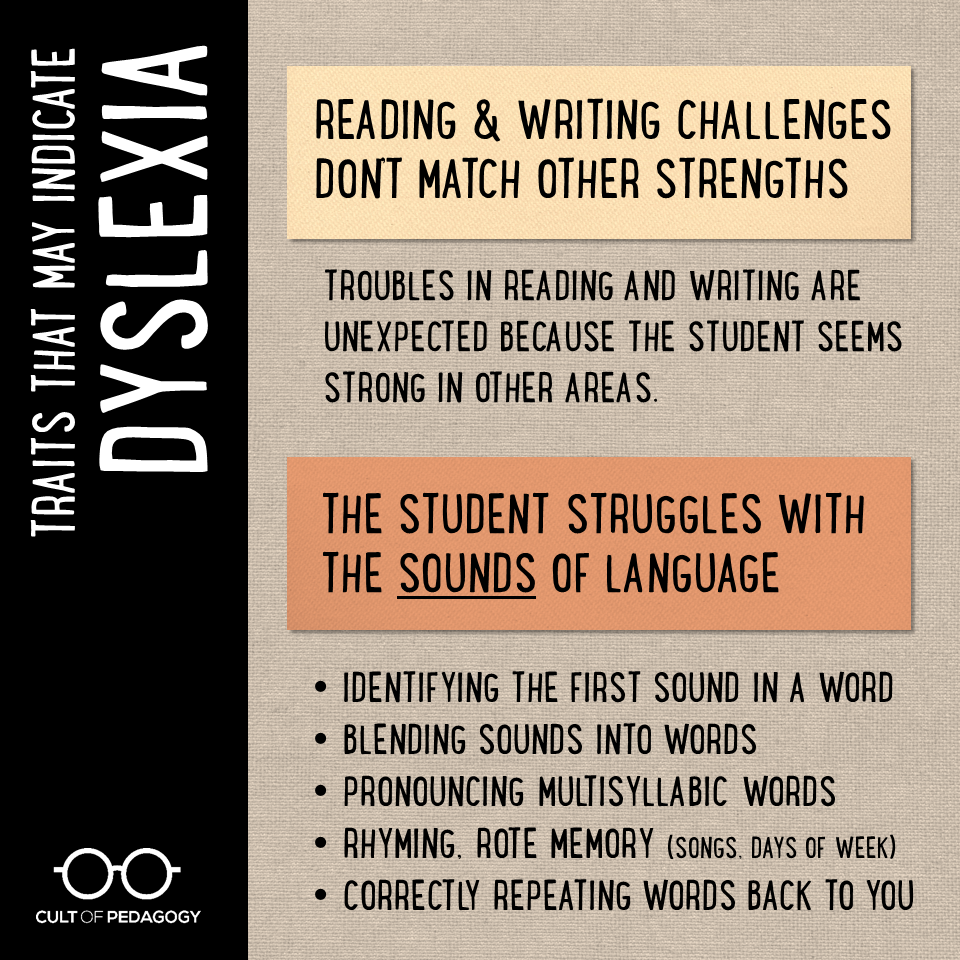

Reading and Writing Challenges Don’t Match Other Strengths

If you find yourself surprised by a student’s difficulties in reading and writing because they seem strong in other areas, that’s one potential sign that the child may have dyslexia.

“So when you look at a child who’s very verbal and good at other things, like math,” Brooks says, “and then the student is having a hard time remembering the letters in his or her own name, we say, wow, that’s so unexpected. This student speaks in paragraphs, has very high vocabulary, is interested in books, and then can’t remember a letter or a letter sound. I think that’s a first clue.”

The Student Struggles with the Sounds of Language

Although many of us tend to associate dyslexia with simply mixing up letters, Brooks says that “difficulty with the phonemes or the sounds in the language is really a marker for being at-risk.”

This difficulty with processing sounds can manifest itself in a lot of different ways. Just a few that you might see in the classroom are struggles with the following types of tasks:

- Identifying the first sound in a word

- Blending sounds into words or segmenting words into sounds

- Pronouncing multisyllabic words like “specific”

- Rhyming

- Rote memory tasks like remembering songs or the days of the week

- Correctly repeating words back to you after you say them

- Not representing all sounds in a word when spelling it

This last item, not representing all sounds in a word, bears a closer look: Consider the way two different students misspell the word butterfly. One might write budrfly, which is incorrect but still has all the sounds represented. The other, who writes burfly, is actually missing the “t” sound. This kind of omission may be an indication of dyslexia and should cause the teacher to observe this student for other signs and possibly refer them for testing.

To learn more about possible signs of dyslexia, see this list from the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

Classroom Strategies to Support Students with Dyslexia

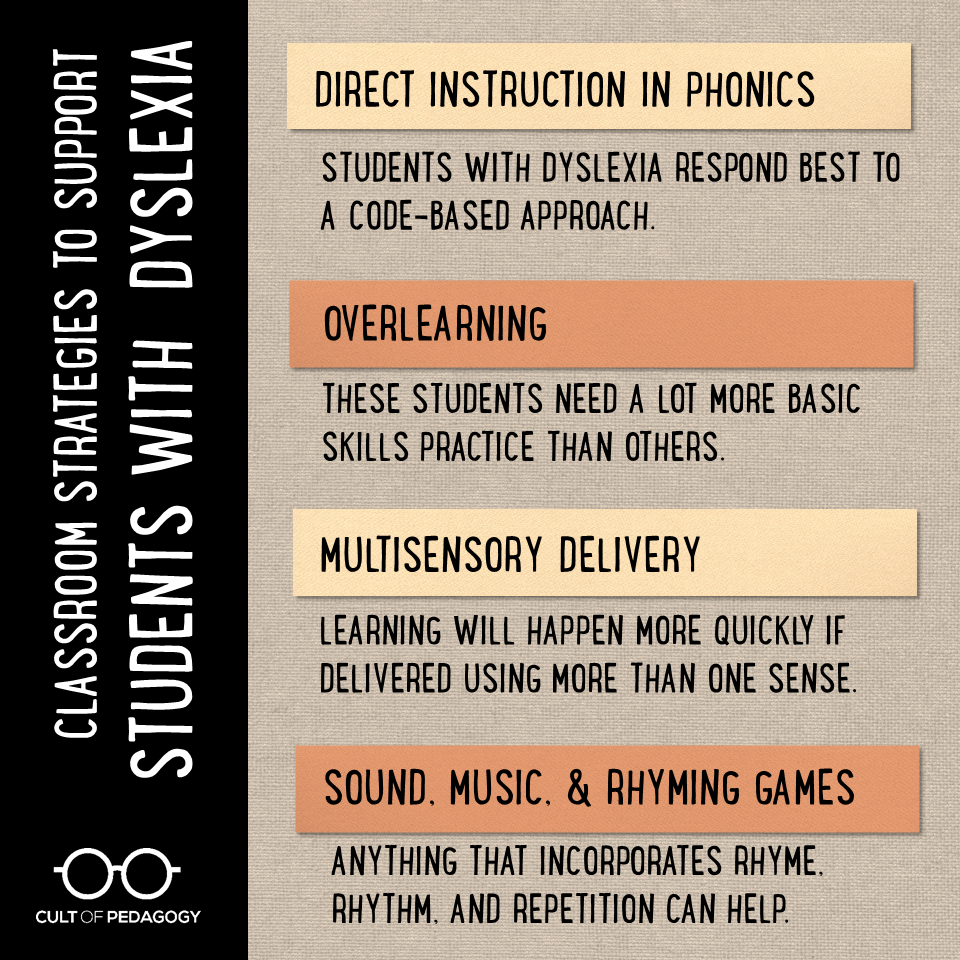

Direct Instruction in Phonics

“In terms of reading,” Brooks says, “we would say that we need a code-based approach, which really means direct instruction in phonics. Some people don’t agree with that, but really what we see in a lot of general education classrooms (is that) the 3-cueing system is not what a student with dyslexia needs. Strategies such as, look at the picture, see what sounds right, guess, see if it makes sense, those are all strategies that are not helpful to a student with dyslexia. So we really need to help them learn the code.”

Overlearning

For students with dyslexia to be successful, they need a lot more practice with skills that other students only need to be exposed to a few times.

“One of the challenges in general ed is everything moves so lickety-split,” Brooks says. “Teachers will say, ‘I taught him consonant blends.’ Well they did that for a week. Students with dyslexia need to practice and practice and practice.

“I always say, it’s like music or practicing soccer. You need to do the scales, you need to do the drills. Teachers say, well this is so boring. And I say, yes, but that’s what the student needs. They know their short vowels on Friday and they come in on Monday and act like you’ve never taught them anything; that’s because they didn’t have practice over the weekend. So we need to remember that they’re not trying to be difficult, it’s just they need a lot of practice.”

Multisensory Delivery

Students with dyslexia can learn more quickly if instruction is delivered using more than one sense simultaneously.

“So for example,” Brooks says, “when the student is writing or completing a dictation, we have them repeat the word, segment it into sounds, and they might use some kind of manipulatives to represent the sounds in the word, name the letters, and then they write the letters while saying the letter out loud. And so in that way they’re using their motor kinesthetic but also their auditory and visual at the same time. I think in classrooms we need to make sure that students aren’t just listening all the time, because we won’t get good results from that. But practicing by touching it, you know, we have them trace the letters, sometimes they’re making the letters on a whiteboard with big muscles and naming the letter as they write it. These are more strategies for our younger students, but really this multi-sensory practice is going to help it stick.”

For older students, who may be more self-conscious about using these strategies, Brooks recommends more discreet approaches, such as tapping out a word’s syllables with their fingers.

Sound, Music, and Rhyming Games

Any games or songs that incorporate rhyming, repetition, and matching syllables to rhythms can give students with dyslexia extra practice with these skills.

Find more strategies in this post from dyslexic.com.

Learn More

International Dyslexia Association

dyslexiaida.org

Tons of dyslexia resources for teachers, parents, and other professionals.

Decoding Dyslexia

decodingdyslexia.net

A parent-led grassroots movement whose goal is to raise dyslexia awareness, empower families to support their children, and inform policy-makers on best practices to identify, remediate and support students with dyslexia.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

I absolutely love your podcast. Do you think you could give guidance on how to handle suspected dyslexia? Do school patches test for that? Or should parents be referred to a specific kind of doctor or something?

Thanks for all you do. You are inspiring!

If you suspect a student has indicators of Dyslexia, you can screen the child easily using DIBELS 8, Aimsweb or other appropriate screening tool that accounts for Phonemic Awareness and RAN, which are two key indicators of potential reading difficulties. The PAR is also an excellent screener. If a child fails the screener, it is very important that the child receive the necessary appropriate follow up to determine if it is Dyslexia. Putting a child in an RTI that never ends or EIP without having any follow up can have devastating consequences for the child. I know one boy who has been in RTI for four years and one girl who was in EIP for three years. Both are Dyslexic, and neither received timely help. A

https://www.schenck.org/admissions/red-flag-checklist. This is a list of red flags.

Children should be identified early in their education. Parents have the right to request that their child receive an evaluation for special education services under IDEA. The Child Find Mandate of IDEA àlso applies. If your state has already created rules surrounding Dyslexia identification and remediation, you will already have a map to follow.

What can we do to help adults who were not ‘diagnosed’ while in school, who were considered LD with a reading disability? Also, are there programs that can be purchased at an affordable price for helping these adults?

We need help here too. My fifteen-year-old son has never been formally diagnosed, but fits every “symptom.” How to help teens and adults?

Hi Kimberly,

We reached out to Lisa to help answer your question, here are her thoughts:

Your local public school must evaluate if the parent requests an evaluation. Even though a teen may meet the criteria of specific learning disability in reading/dyslexia, it does not mean your son will qualify for direct services. After the evaluation process, the team will meet to see if your son is eligible for learning center support, co-taught classes, accommodations, etc. Many teens prefer to seek services outside of school and thus work with a private tutor. Colleges offer academic support and/or accommodations if the student has a letter and goes through the proper channels at the college’s support center. Help for adults who are not in school is a little trickier. Some public adult literacy programs have specialized tutors. Many private tutors specialize in working with adults with dyslexia.

We hope this helps!

Hi Catherine,

We reached out to Lisa to help answer your question about affordable programs, here are her thoughts:

Many students with dyslexia are not diagnosed with dyslexia during their school years and are often diagnosed in college or never diagnosed. Remediation for adult learners is ideally done with a skilled tutor. Check for adult programs in your area that specialize in dyslexia. The International Dyslexia Association is a referral source, or check with your local library, or your primary care physician may have referrals for you.

We hope this helps!

1. How about adults, who

Need help aswell?

2.Where can adults get tested?

Great question, Terrel. If you scroll through the comments on this post, you’ll see a couple of responses from Katrice Quitter that should be helpful. She reached out to Lisa Brooks, the interview guest, back in 2019 to get her thoughts on this question.

Thanks for the thorough article. The links are also helpful.

I would like your help my daughter has this. But the teachers cant teache her i have spoken to the school i have been to iep meetings but the school keep telling me they can teach her. She is now in the 7 grade and still cant read.

Please tell me what to do.

Thank You

Robin Howard

Hi Robin,

I’m really sorry to hear this. If you haven’t already, I’d check out some of the links to the outside resources that are in the post. Find whatever information you think is relevant and then schedule a meeting with her teachers. Share this post as well as the other research, to see what, if any, strategies are already being used at school and how often. Then as a team you can discuss other things from the articles that can be implemented.

As an aside, if your daughter has a lot of difficulty segmenting sounds in words, try using sound boxes; this is a really great activity that applies phonemic awareness, segmenting sounds, and phonics. Here’s a link to a video that demonstrates one way of using this strategy.

Hope this helps!!!

I would like to respond to Robin Howard. I would just like to say I feel your pain! My daughter (9) had a very hard time with reading and spelling and the school district did some interventions, but nothing seemed to work. I took the issue into my own hands and had my daughter tested for dyslexia because I had been doing my own research and all the warning signs seemed to point to that. It was very expensive and my parents helped us with that. I know it can be totally impossible for most people (us as well) to do that expensive testing. My point in bringing that up is that you probably don’t need to confirm it thru testing. What I DO suggest, however, is to get her one-on-one tutoring immediately. We have found a tutor through one of the dyslexia sites and she does the Wilson program twice a week with my daughter. It has been only about 3 months but I already see such a difference in my daughter’s reading ability, but even more so her spelling ability. It has literally given me hope that she will be okay in life academically. Dyslexia can’t be “cured” but it can totally be overcome! The tutoring is expensive, but it is a must if your school district won’t do anything. My public school district doesn’t even really understand dyslexia or what methods help so I understand feeling totally alone in this process. I hope this helps!

Hi Beth, I am a Certified Academic Language Therapist and I am happy to hear that you found a local tutor to help. I agree that the schools are not always the best place to turn for effective reading instruction. Another option for parents that do not have access to local professionals is Structured Literacy Therapy though Lexercise. I have worked in public schools for over 12 years and now work as a CALT to deliver Orton-Gillingham lessons online via webcam. If you know anyone looking for research based support that follows all of the criteria by the International Dyslexia Association, please share my link so I can help them through this confusing journey. https://www.lexercise.com/consultation?group=13&clinician=464

If you want to learn more about reading differences/word-level reading difficulties/dyslexia (whatever you choose to call it) and how to teach so children learn to read or how to correct a reading issue, read David Kilpatrick’s , Equipped for Reading Success: a Comprehensive, Step-by-Step Program for Developing Phonemic Awareness and Fluent Word Recognition. The best $50 you will ever spend for your classroom! It is insightful, interesting, explains how we learn to read AND tells you how to teach so children will learn to read and what to do if they are older and still struggling!

Someone recently told me that Kilpatrick claims “Early intervention approaches based on scientific evidence … can prevent reading disabilities.” If this author actually believes “disabilities” can be “prevented” then he shall receive $0 from me.

Here is the full dubious claim, made in a facebook group, by someone I won’t bother to credit here:

“According to David Kilpatrick, author of Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties (2015), “While there may be a genetic/neurological basis for reading disabilities in a majority of cases, we should feel encouraged by the fact that there are ways to prevent and intervene to help children overcome those difficulties” (p. 120). Furthermore, in Kilpatrick’s more recent book, Equipped for Reading Success (2016), he states, “The findings from countless research studies have been consistent and clear: Students with good phonological awareness are in a great position to become good readers, while students with poor phonological awareness almost always struggle with reading. Poor phonological awareness is the most common cause of poor reading. Reading problems can be prevented if all students are trained in letter-sound skills and phonological awareness, starting in kindergarten. You may have heard there is a neurological/genetic basis for reading difficulties. This is accurate. This is apparently because phonological awareness difficulties often have a genetic basis. However, the good news is that despite their neuro-developmental origin, these difficulties are preventable and correctable” (p.13).

I don’t know anything about Kilpatrick or his book, but from the quotes excerpted her, it doesn’t look like he’s saying the disability can be prevented, but rather that if it’s recognized early enough, the difficulties associated with the disability can be predicted and accommodated with intervention before they become a problem.

Where was this article when I started teaching several years ago? This is a must for all beginning educators. I absolutely love your postings. Thank you so much!!

Thanks so much, Mary! I’ll make sure Jenn sees this.

Fantastic and useful information! Thank you very much for this!

This is a good article but I would really like to see how to help middle school and older students who have somehow been overlooked for dyslexia. There is no pullout class for phonics intervention likely to happen in most middle schools, and using something like a soundbox in a class for an individual, or exposing an entire class to a soundbox more than once or twice would not be realistic in a middle school classroom. I have great hope that our state’s new screening for dyslexia in the early grades will help in the future, but what about my students now?

Hi Beth,

If you’ve got kids who show traits of dyslexia, but haven’t yet been tested, or if it’s been a few years since they had an evaluation, then you or their parents can refer them for an evaluation. If they qualify, that should help them get the services they need. In the meantime, you may have kids who aren’t dyslexic, but still need support. There are a lot of ways to differentiate assignments and implement accommodations for kids of all ages. Be sure to check out the links that are in the post for ideas. A lot of them can be used with older kids.

Here are some other resources that you might find helpful:

8 Study Tips for Middle-Schoolers with Dyslexia

9 Ways to Help Kids With Dyslexia Remember and Pronounce Long Words

Teaching Teens Who Struggle With Reading: What Can Help

Beth’s questions (October 15) in her comments are also my questions! How do I help correct dyslexia in my 6-8 middle school Title 1 classes? Is there a recent research-based phonics intervention program for middle school students?

I use Wilson’s “Just Words” program for my middle school students.

Hi Beth,

Great question as you focus on “What do I do now?” for students. We reached out to Lisa for some guidance, here are her thoughts:

Dyslexia laws will change things for the future. Teachers can certainly teach students phonics basics such as the six syllable types and how to break down polysyllabic words. It is hoped that this will not be considered specialized instruction in the coming years. In the meantime, focus on accommodations: extra time for reading/writing assignments, use of technology for writing, audio books for longer amounts of text, not penalizing for spelling mistakes.

We hope this helps answer your question!

I’d be curious what support looks like for children with dyslexia in a mathematics classroom.

I suspect that many of the supports described here are also helpful for dyslexic children. Specifically gestures to point at exactly what is being talked about, annotation to highlight features of the mathematics, the Four Rs that introduce some repetition of what is being discussed in various ways and a record of the discussion, the use of sentence frames/prompts to support production of language, and the use of think/pair/share to provide more processing time for students.

But what other supports exist for dyslexic children in mathematics and more importantly, how can we build these supports into our everyday instruction to reduce the need for external interventions?

Hi David!

We reached out to Lisa to see if she would be able to share what support looks like in mathematics, here are her thoughts:

Some suggestions for math support for students with dyslexia: limited teacher talk, direct instruction with a significant number of examples for over-learning, only a few problems on a page allowing a lot of white space, hands-on manipulatives, graph paper or lined paper held horizontally to line up numbers in algorithms, a reference notebook for formulas.

I hope this helps!

I think this is super valuable information! The only piece I’m struggling with is the suggestion that kinder or first graders be referred for “testing.” Perhaps you could clarify what you mean by that? As a special education teacher, I find it incredibly frustrating when children that young are referred for special education testing, as there’s RARELY a large enough discrepancy for a child to qualify at that age unless there’s far more to their profile than just dyslexia. It’s disheartening when I test a child that young, they don’t qualify, and then we have to wait to test them again. Meanwhile, they may be struggling their way through the next year, but we’ve knowingly stolen their opportunity for testing at a time when a discrepancy might actually appear (end of first, beginning of second).

Hi Laura!

We reached out to Lisa to help provide clarification about testing, here are her thoughts:

These days, assessment of all kindergarteners begins the moment they step into the classroom. We begin looking at their ability to blend and segment sounds by October of kindergarten and put into place interventions through regular education if needed. We no longer use a wait to fail model; we try to intervene as quickly as possible. The Response to Intervention model has helped many children receive research-based intervention without having to be on an IEP.

I hope this helps!

I’m 69, so of course NONE of these labels existed while I was going to school. I simply learned by myself that I had to do things a little differently than the other kids — but I was NEVER chosen until almost last when we had a team spelling competition!!! I knew I had to learn the sounds; I used rhymes to help me remember — I still do — and learned there were rules in spelling and reading; and I HATED those exercises that were projected on the board with words blacked out at various paces and we were suppose to read — and remember — selections. I still graduated salutatorian of my class. My college roommate was a special ed major and used me as her guinea pig to practice her tests. To make a very long story short, she and her professor discovered that I am dyslexic!!! No way, she originally told her professor! She’s on the Dean’s List! Flash forward. I graduated with BS in Education (English/theatre), hold a Masters in Ed Admin, taught HS English for too many years, and retired as a principal of an alt ed/at risk school for expelled/suspended 6th – 12th grade students (and I absolutely LOVED working with “those” kids!). Still at it going on 48 years since I’ve been subbing for the last 7 years. Just told my students — and still do — with a lot of work, one can overcome just about anything. My English students were always amazed when I told them I was dyslexic — they knew what it was. Just told them that sometimes some of us need to learn differently, but don’t give up! Loved that they seemed to enjoy testing me with “Spell That Word!” Got to teach them the importance of rules in all things — especially spelling when one is dyslexic!!! If I learned nothing else from living with this disorder, I discovered it is important to share with your students. They’ll love you anyway!!!

Thanks so much for sharing your story Susan.

Things like this make me really mad. Teachers want to call themselves professionals, yet they knowingly allow themselves to be ignorant in matters directly relating to their profession. As a physical therapist I have to know the side effects of medications and withdraw symptoms, common medications’ mechanisms of action and symptoms of interactions. I’m not a pharmacist or a doctor, but these are things that directly affect the effectiveness of my work. Teachers should take some responsibility for themselves and get educated on these obvious conditions that will be affecting how well they are able to do their job! There is no excuse for this laziness, and I don’t think teachers should be crying for more money when they are doing the bare minimum and not acting like a professional in any other field would.

I don’t think it’s accurate to say teachers “knowingly allow themselves to be ignorant.” That kind of doesn’t make logical sense, since knowing about a lack of information in some area is really the opposite of ignorance. Having said that, lots of teachers are frustrated with their preparation once they enter the classroom and realize how much more training they probably needed to know to do the job well. Plenty of teachers work very hard to fill in the gaps as they go with professional reading, book studies, and attending conferences. The fact that my podcast has reached over 6 million downloads tells me that there are many, many teachers who are committed to learning everything they can to do this work well.

Hello, I agree with you. I have many colleagues who are trying desperately to learn how to support their students who struggle. With the lack of specific teacher training in the area of reading it is really “left up to” teachers to search out supports. I have a colleague who has been teaching for 20 years and doesn’t know how to do a running record. I think that teacher training programs need to spend less time on theory and more time teaching basic skills all teachers should have. Most teachers “know” when something is wrong but lack the skills to correctly diagnose the issue and then provide the supports needed. Your blog has really helped me and I will definitely be sharing it with my colleagues.

Thanks for the tip that paying attention to multisyllabic words can help in the detection of dyslexia. My neighbor is considering to make his daughter undergo special education because of her inability to speak much despite being 4 years old already. Hopefully, she will still be able to learn to read well despite her speech problems.

This is really good information.

I am an assistant principal at a middle school and I am also dyslexic.

One area of concern that I am seeing is the chronic stress that students with dyslexia or that learn differently are experiencing. They are coming to school feeling defeated and less than. They will sit in the back of the room trying not to be noticed, hoping the teacher will not call on them. We need to make our classrooms a safe space for these students. Start by building up their self confidence. Give them a safe, nonjudgemental space they feel safe enough to participate in.

‘Dyslexia is a language based disability’ – What are the methods as a teacher, would you employ to find out the core problems associated with this ability?

I have doubt ma’am.. can you please help me to understand this..

‘Dyslexia is a language based disability’ – What are the methods as a teacher, would you employ to find out the core problems associated with this ability?

With an example…!!!

Hi MR,

A lot comes down to understanding the traits that may indicate dyslexia and observations/data teachers collect as they work with students. At the end of the post there’s a link to dyslexiaida.org, which includes a wealth of information beyond what this post could cover. If you get a chance, check it out!

As someone who has dyslexia, I agree wholeheartedly with a lot of this information. I wish more had been know about it when I was in school.

I like the idea of using all the senses when helping all students, not only students with dyslexia. I use it in my world language classes.

Very insightful, thank you!

interesting information on how to spot dyslexia

Great info, thank you.