Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Screencast-O-Matic and Microsoft Inclusive Classroom

My daughter was recently given an assignment to create a model of a volcano. It was a group project, meant to be done entirely at home, and the only clear requirement was that it had to look like a volcano, with extra points if it could actually erupt.

And so it began: My daughter and I planned when her two friends would come over to work on it. I texted their moms and we set a date. We also figured out what supplies she’d need from the craft store and when I would drive her there to get it all. We ended up spending about $40 on modeling clay, spray paint, fake palm trees, and tiny dinosaurs. And that’s after I said no to about $40 worth of other stuff she wanted to get.

The three girls met at our house one afternoon. One of the other parents brought over the materials they used to make the volcano erupt. I insisted that they do the project in the dining room, where we could make sure they stayed on task, instead of my daughter’s bedroom, where I knew they wouldn’t. My husband helped them hunt through the basement for an old lampshade to give the model some height, helped them figure out how to make the clay stick to the lampshade, then did a few trial runs of the “eruption” with them, so they knew it would work in class. A few days later, I drove my daughter to school and helped her walk the model safely into class.

So much had to happen to get this assignment done, and very little of that was actually done by the three students whose names went on the project. I’m not saying my daughter and her friends didn’t build the volcano, but they got a lot of support along the way, and if any of that support had been missing—time, transportation, money, space, suggestions, supervision—the project would have been less successful.

When I ask my daughter about the other student projects that were turned in that day, she confirms my suspicions that they ranged in quality: Some, she says, were “huge and detailed,” while others consisted of little more than a painted water bottle.

Though I never confirmed it, I suspect that each of those projects got vastly different grades.

What Are We Measuring?

Although a movement is growing to eliminate grades, they are still a reality for most of us, and they impact everything from college admissions to whether students get to go on certain field trips. So it’s important that we do whatever we can to make sure they measure what matters.

And in too many cases, that’s not happening. Take the volcano project: The grade students received on that ultimately reflected the resources each group happened to have at home—not what they learned or even the effort each student personally put into the task. Those with the “huge and detailed” ones probably got the best grades, and those with the painted water bottles probably got the lowest.

Or consider these other scenarios:

- The student whose essay gets a D, because even though he organized it pretty well, made some strong, well-supported arguments, and used rich vocabulary, his teacher’s rubric allotted 40 percent of the grade to neatness and correctness, and he had a lot of mistakes. The teacher lets him revise for a higher score, but only gives half credit for the points earned the second time around.

- The student who raises his grade by earning extra credit for donating tissues and hand sanitizer to the class.

- The student who gets a C on an assignment that requires her to compose an original song to explain a constitutional amendment. Despite her solid understanding of the constitution, she doesn’t happen to have a knack for writing lyrics and music.

- The student whose project is turned in a day late and gets only half credit according to her teacher’s “no excuses” late policy.

In all of these cases, the grade is not an accurate representation of what a student has learned. This is a problem of design: When constructing assignments, assessments, and grading policies, every teacher makes dozens of small decisions that determine how much a grade reflects a student’s academic work and how much it reflects a mishmash of other factors. Those quantities are different for every teacher and every assignment. Despite that, we tend to treat grades as if they mean the same thing all the time.

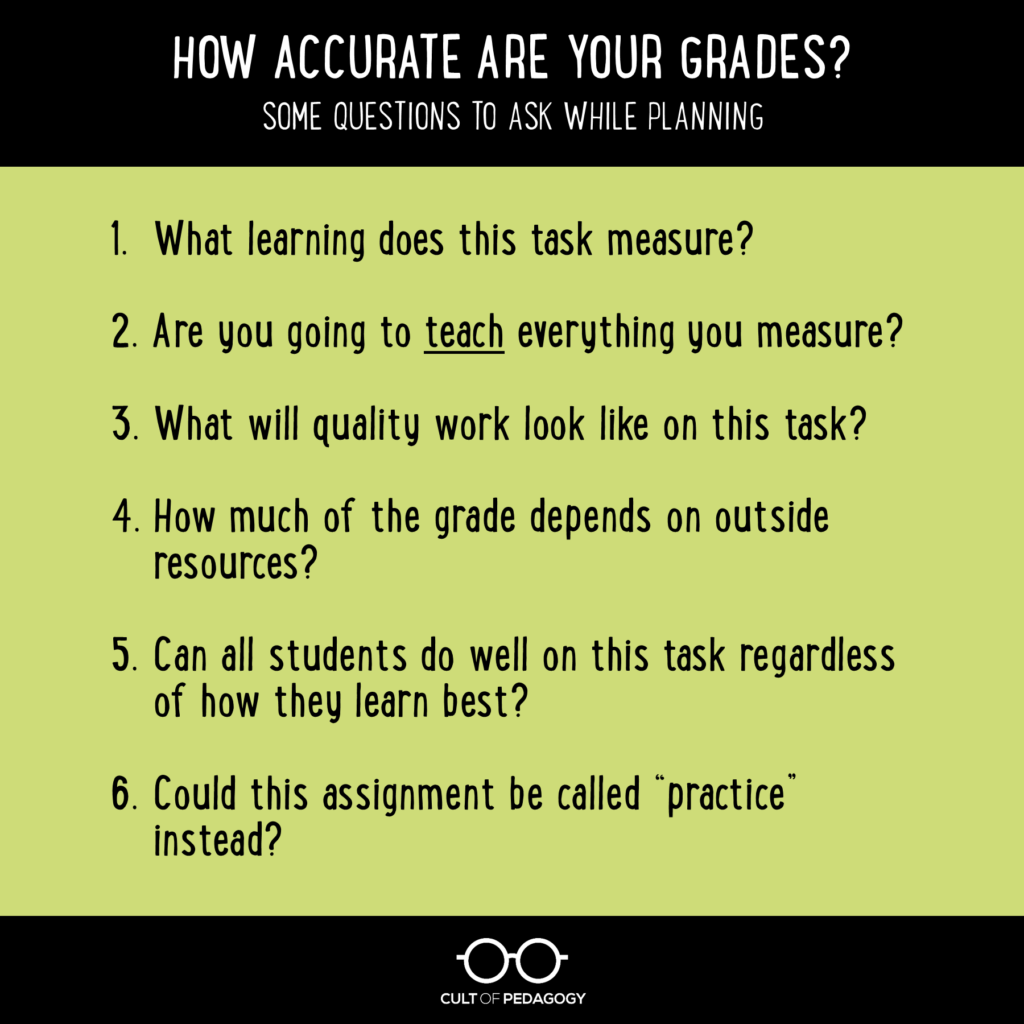

Some Questions to Ask While Planning

So what’s to be done about this? If you or your colleagues aren’t ready to completely overhaul your grading system (again, see how others are doing that here), or you haven’t moved to standards-based grading, you can still improve the integrity of traditional grades by considering some important questions while planning for instruction.

1. What learning does this task measure?

The grade on an assignment should match the learning students are supposed to be doing in your class. This sounds simple, but it amazes me how often I see assignments that seem to have no real connection to what the curriculum says students are learning.

If your standards require students to “be able to explain how geography impacts culture,” then assignments should ask them to do some variation of that: explain how geography impacts culture. If, instead, they are making a relief map that shows geographic features, and their grade is based largely on how accurately they represent those features, then they are being graded on map-making skills, not on the standard.

This is especially problematic when qualities like “creativity” are part of your criteria. For one thing, this term means completely different things to different people, so students will have to guess how to perform well on this metric. More importantly, grading for “creativity” on an assignment that is supposed to measure something else will distort the results, making it much harder to tell who actually mastered the skill.

2. Are you going to teach everything you will measure?

We often assign points for skills and qualities that students happen to bring with them, but are never taught in our class.

Suppose you assign a group project, and part of each student’s grade will be based on how well he or she worked with the group. Collaborative skills are important, absolutely, but if you’re grading for them, shouldn’t you also be teaching them?

Similarly, if you’re going to ask students to do an essay-type question to demonstrate their learning, and part of their grade will be based on how effectively they write, then ideally, some of your teaching prior to that assessment should give students practice in the kinds of writing skills you want to see on that task.

If our lessons don’t prepare students to do well on graded assignments and assessments, then those grades aren’t a fair measurement of learning in our class.

3. What will quality work look like on this task?

When creating assignments, we often have a general idea of what a good end-product will look like, but we don’t always know for sure until the work gets turned in. At that point, it’s too late for students to rise to our expectations, and if we haven’t clearly defined them ahead of time, it’s easy for personal bias to cloud our judgment.

We’ll get better work from students and judge it more fairly if we identify and communicate the criteria for success ahead of time. Many teachers accomplish this with a rubric given to students before they start. These come in different formats: A growing number of teachers are finding that students appreciate the single-point rubric for its clarity and ease of use.

I would also strongly recommend you do the assignment yourself as if you were a student—a process we call dogfooding. This will help you get much clearer on how you define excellence for this assignment.

4. How much of the grade depends on outside resources?

If an assignment is going to be completed partly or entirely at home, take a good look at how much the available resources outside of school could influence the grade. Things like transportation, money for supplies, access to technology, or help from an adult can all contribute to an end product that looks impressive, but may not directly reflect that student’s academic skill or effort.

If your assignment is designed so that the focus stays on content and skills, and if you set things up so that the majority of the work happens in class, the assignments you get back should be a more accurate representation of what each student can do.

5. Can all students do well on this task, regardless of how they learn best?

If an assignment is delivered with only one type of learner in mind—with instructions only given verbally, for example—some students will be behind before they even start. Ideally, every task will be designed in a way that all students can access.

Universal Design for Learning is a framework that can help teachers design materials so that all learners have equal access to them. To learn more, watch this overview video or explore the UDL Guidelines developed by CAST. As you work to make your assignments more universally accessible, take a look at some of the great accessibility tools Microsoft offers teachers for free.

Similarly, if the task favors students who happen to have a specific type of artistic skill—the way the constitutional song assignment did for students with musical talent—others who might have preferred to demonstrate their learning through an essay, a poster, or a video are less likely to shine.

Instead of limiting student products to a single, narrow option, consider whether you can give them choices in how they demonstrate learning. If the volcano project had been designed for students to create a model for how a real volcano works, that model could have been done with a paper diagram, in a video, with a student-produced skit, or with a physical model. Not only would this give students an opportunity to put their unique gifts to use, it would also provide options that cost a lot less money to bring to fruition.

6. Could this assignment be called “practice” instead?

Too often, teachers give grades to all classroom activity; they are convinced that kids won’t do something unless it’s going to get a grade. And that means tasks that are really meant to give students practice in a skill or early exposure to content are ultimately included in final grade calculations.

They shouldn’t. Instead of making everything graded, have students do some class work as practice, in preparation for a task that will be graded. So if students have to take a test on long division, require them to do enough self-graded practice pages until they get 80 percent or better. These problems won’t be part of their final grade calculation, which also means you don’t have to grade them, but students can’t take the test until they can demonstrate proficiency on the practice, and their grade on the test will count. This way, their grade will reflect their mastery of long division without penalizing them for how long it took to master the skill.

Other Factors to Consider

Late Work

Some policies on late work can have a significant impact on student grades, so that a student who turns work in late can have very low grades, even if they have mastered the content. In classes where late work is penalized, a grade is a reflection of the student’s time management, or of stress, or perfectionism, or dozens of other possible factors. What it isn’t is a reflection of learning.

Despite this, many teachers feel that taking points is their only option for responding to late work. This piece by Starr Sackstein explores this dilemma and considers some ways teachers can address the problem without docking points. Spoiler alert: It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, because students turn work in late for a variety of reasons. “At the root of every challenge we face with students of all ages is a story,” she writes. “Our job as teachers to figure out what the story is. Some students will be an open book and others we will need to be detectives to figure stuff out. Don’t give up on the kids. Giving a zero is giving up and almost expecting them to do the same.”

Extra Credit

Giving points for anything that doesn’t directly reflect learning can have an incredibly distorting effect on grades. In some cases, it elevates grades, giving the impression of mastery without the actual mastery. In other cases, it masks problems: If a student misses a few test items, but erases them with bonus points, that student could fly under the teacher’s radar and miss opportunities for reteaching.

Students who are doing so well on the regular class work that they finish early don’t need extra credit, they need differentiated assignments and more challenge. Students who do poorly on assignments don’t need extra credit to make up the missing points; they need opportunities to re-do and improve on the work.

This piece by Joy Kirr does an excellent job of showing how a variety of typical extra credit assignments are rife with all kinds of problems.

Grade Averaging

If you calculate your grades by simply averaging them—dividing the points earned by the total possible points—your final course grade could be doing a poor job of representing what your students actually learned in your class. In this piece on the pitfalls of grade averaging, Rick Wormelli uses specific examples to illustrate this problem.

Having graded this way myself, I always liked the simplicity and convenience of grade averaging, so I know that the thought of trying some other system will likely be daunting. But if it means our grades will have more integrity, it’s worth it.

One alternative to consider is something called a decaying average, which puts more weight on assignments done later in a learning cycle. In theory, this recognizes that skills should improve over time. Although this approach seems to work better in skill-based classes, it shows us one way to rethink the way we calculate grades so they are better aligned with who our students are as learners.

Grades are inherently imperfect. To truly assess our students’ learning, we need to get to know them, observe them, and study a wide sampling of their work over time. When we reduce all that to a single measurement for the sake of efficiency, we lose that bigger picture. But as long as grades remain a reality in our system, let’s be thoughtful and deliberate when we calculate them. ♦

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Wow! This was an eye-opening article. While I try to only grade what I want students to know and understand, this article showed me areas in which I can definitely improve. Thank you! Saving to use as I plan next year over the summer.

Thanks, Jen, for again putting so eloquently into words what many of us are thinking, and giving practical advice for changing practice. Great stuff as always!

In junior high school, my German, French and Science teacher informed a few friends and I about his university studies or the lack when he grew up there of in Germany. Although his entire family in Europe had informed him that even though he was surrounded by royalty, and their occasional party lifestyle, they themselves were not connected. However, with a snap of his finger, he would tell them,” What do you mean, I’m not connected?” When it came time for my teacher’s time to to take Germany’s national arbiter, he failed the science portion of the test which meant that he could not get a job until he did. Privately, he kept repeating how difficult it was for him to pass it, but when I questioned him if each time he took it his scores improved he stated, “Why, yes it did!” After moving to Southern California, and then returning back to Northern California a slightly older former student of his once informed me that he had passed the arbiter! What he did not know, was his built in fear to take the test, and his plan, as he tried to tell me, to stop taking the test all together. The person who brought the news to me, had no idea that our former academic teacher whom we never would have met had he first heeded his family’s academic forebodings. This is meant to underscore what might be a down turn in academia where there really was no!

This definitely makes me sit down and reflect on my grading. This is a very difficult topic because there’s not a simple solution for this but I’m sure that taking those questions into consideration will be a great start to improve my grading ! Thank you very much this was very helpful because it wasn’t instructions on how to do things better but some good points we need to reflect upon to be more accurate that our grades really represent what we meant to.

Great post, Jennifer. Many thanks. Some other complications that I’d like to highlight from your volcano anecdote: Equity is a big one. Not all families have $40, mobility, available parents, etc. So the assignment you describe is unavoidably punitive to needy children.

Group grades is another large issue. There is no way for the teacher to track the individual learning of each student in a group project (at least in the way you describe it), and so there is no guarantee that the same grade represents the actual learning of each partner in the project.

Thanks for your fabulous posts.

Craig, great insight. It reminds me of a book all must read…Where can I build my volcano? written by Pat Van Doren. it describes the difficulty of a homeless girl to function in school. We do indeed need to “Pay” attention to ALL the students. One of my questions about the volcano project anyway, is what do students learn? Why not investigate what happens to communities in proximity of a volcano, is there an idea children can discuss to help keep the community safe? this is critical thinking. What is real about baking soda and vinegar in a soda bottle?

Thank you…I’m an AVID and English teacher and see such HUGE variations in grading, it makes me question the validity of all grading systems!

I make each assignment of the same “type” worth more points than the last one of that type, over the course of the year. This has the advantage of transparency — students understand quickly how and why an essay might be worth 40 points in October but 70 in January, and 100 by June. And it combines the ease of averaging with the advantages of decaying averaging.

Two pieces of advice:

1. Use feedback and feedforward as assessment, not numbers. 2. De-establish ‘grading’ at every level. Much as we might like, I don’t think the current system can be thoughtful, deliberate or, most importantly, caring.

Do I follow my own advice? No. I am not allowed to.

When you X-ray assessment’s spine you see it for what it is–a rigid hierarchy whose purpose is to separate the goats from the sheep, the wheat from the chaff, the privileged from the precariat and the unnecessariat. Institutional imperatives rule and the ultimate rule is survival of the institution.

Having said this, thank you for the inspiration and especially noting how the privileged have advantages at every level.

Hi Jennifer!

Thank you so much for the post! This really resonated with me as a technology teacher and coach as my courses are primarily project based and as a result the actual assessment process can be somewhat ambigous in nature.

I particularly liked your suggestion to do the assignment outselves first! Soo necessary!

Thanks again 🙂

Marisa

This ep was insanely helpful. I am desperately trying to push my professors to break out of the empty traditional methods they are prone to and this ep covered a huge amount of the contentions I have against them.

Dogfooding. THAT IS SOOO NECESSARY. Up to this point I’ve been forced to see the education I’m getting as a hazing ritual that’s out of control. My feelings of resentment are doubled by any indication that causes me to suspect that what is true of all hazing rituals is also true of my college experience, that those before me didn’t actually endure the suffering that they deem is necessary for me to “just get through.” Dogfooding will be a repeating slide on any lightning talk I can get them to listen to.

I can’t tell you enough how much hope your podcast gives me to actually convince my professors to stop torturing us and to give us a real education.

Some great ideas in here like dogfooding and thinking about supports students have outside of school. In reference to late assignments – I do not deduct late assignments as long as they are turned in the same marking period (9 weeks). However, there is always a clear trend as to what students frequently hand in late assignments; it does not vary much.

I really enjoyed this post! I do wonder about using a point system for classroom management and whether or not it can inflate/deflate grades, making them less representative a student’s understanding of the content. I ask this specifically because Michael Linsin from Smart Classroom Management recommends using daily points for upper middle and high school students. Maybe it works because under his system, you “teach” and model the behaviors, thus making them grade-able? And if grading classroom behavior is beneficial, how do we weight that grade appropriately? I think Linsin recommends the daily points be worth 50% of the overall grade (see page 10 of his SCM Plan for High School Teachers). But that sounds like a ridiculous amount of weight given just to behavior….. Thoughts?

This is a great question, and there was a time I would have probably agreed with him, but now I’m not so sure. I really like most of his posts on classroom management, but I’m not familiar with this particular system. I think there are some people who would argue that behavior and grades should be completely separate, but then that leaves you with little currency. I would like to hear what others think about this, but I’m leaning toward a much, much smaller percentage. I agree that 50 percent sounds way too high. Wish I had a more concrete answer for you!

This is a very concise and helpful post! Thank you!

I wonder what your thoughts are about conversations with students and observations you make? How do they fit into a system that includes grades? Younger students don’t always produce products (assignments) you can grade.

Hi Devika. When I taught 1st Grade, conversations and observations were always an integral part of my assessments. I think this data could and should fit into a grading system. Just be sure expectations and the meanings of letter grades are clearly determined and communicated ahead of time. At the end of How to Turn Rubric Scores into Grades, there’s a good conversation between Jenn and Amy from 4.23.18 that I think is very similar to what you’re asking — I’d check it out.

I work at a University English Language Institute where all my students are non-native speakers, and all my classes have multiple L1 languages. I have spent the last two years working on improving my rubrics so that the criteria are quantified (although this can sometimes be just numbering individual sub-criteria for inclusion in a category), linguistically useful for student English level (we are in a public/private partnership that sends us recruited students of all levels) and, most importantly, provides a strong base for students to really understand where the problem is.

When I started this project I thought that the solution was just getting the rubric criteria quantified, but as I worked with the rubrics and the criteria I realized that for the rubrics to be really communicative they would have to use level appropriate language. To do this I have started to get help from some colleagues that use Lexical Methodology and that has helped a bit, but I am still working at it to improve communication without students having to turn to translation or dictionaries. Right now I am using an approach where I bring printed rubrics into class for students to study and question for meaning and vocabulary which I then use to rewrite the rubric for student available clarity.

The results so far have been very positive, students demanding higher grades because they “must have full marks” have dropped to almost zero. Just yesterday a student remarked that looking at the rubric explained a lot and changed how she and her group were going to teach their part of the project. All this is good, but I feel like the rubric battle is being lost because of the rubrics I see in the textbooks, and in the grading of teachers coming out of our Ed School. More and more are turning out rubrics based on a five point scale that means that students don’t get any reasonable feedback from the rubric and often either get “full marks” or failure when they are really only partially wrong, or incomplete in their understanding but there is no way to give them any useful feedback.

What I am pointing to is that there is a systemic problem in the textbooks (for my tiny corner of the pedagogical world anyway) that either moves grading into inflation or … maybe emptiness is the best way to think of it. The students get nothing but a final grade that is, in itself, empty of information for them about what they did that gave them the grade the rubric shows.

I would love to hear your opinions and ideas on rubrics and how they can be leveraged to provide more complete and useful information to students as well as more practical approaches to rubric creation.

Hi! Thanks so much for sharing. If you haven’t already, check out Jenn’s posts Know Your Terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics and especially, Meet the #SinglePointRubric. You may also want to take a look at the resources on her Assessment & Feedback Pinterest board to see if you find anything relevant to your needs.

Great post. Do you recommend “standards based grading” and, if so, do your rubrics include standards? Thank you.

Hi Jennifer! This is Debbie Sachs, a Customer Experience Manager with Cult of Pedagogy. I talked with Jenn and her personal opinion is that everything she’s ever heard about standards-based grading sounds like that it’s a much better alternative to traditional grading. But…she’s never worked at a school district that used it, so she doesn’t have personal experience with it. As an aside, the school district that I worked at uses a “no grades” system for K-5. My experience with standards-based grading just made a ton of sense to me — less focus and time spent on points, averages, and things that had nothing to do with what we really needed to assess. More time was spent on monitoring students to ensure they were on track and then deciding what we needed to do to get them there (or beyond) by the end of the year.

Jenn’s <a href="https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Rubric-Pack-3414843″>Rubric Pack includes 4 styles that are fully editable and customizable so that teachers can include standards of their choice.

Hope this helps!

How can you design “gatekeeper” practices for writing and manage reading everything. I have an average of 29 kids in my 5 sections. We are also expected to read everything they write. I love the idea, but I don’t know how I can manage all of these papers.

I could always tell in collage when the professor did the homework themselves. Professors who didn’t often assigned nearly impossible stuff for almost no points.

Hello all, very good topic. All excellent points. The concern about grades is valid and many I have believed for quite some time. Grades. Some students are too caught on in the “grade” the concept of learning slowly slips away. So we children, we are taught very young that students who receive A’s are bright and those who receive Cs are, well, ok. Grades represent very little, in my opinion, but we are an educational system that encourages As not Cs. Take another perspective. Northern European schools take a student-teacher-system collaborative approach and view students as “partners”: Interesting…

Tanaka, M., Naylor, R., Ursin, J., & Zavale, N. C. (2019). THE FUTURE OF STUDENT ENGAGEMENT. Student Engagement and Quality Assurance in Higher Education: International Collaborations for the Enhancement of Learning, 162.

Joy Kirr Extra Credit link is broken here is the piece if anyone is interested.

https://www.teachersgoinggradeless.com/blog/2017/11/18/extra-credit?rq=extra%20credit

Thanks so much for sharing this Shaylee! We’ll get it updated in the post soon.

Great pod cast! Wonderful comments and logical points about grading, rubrics, extra credit, late work and the dreaded zero! I have never been a fan of the zero, but also had not figured out what to do about that assignment that just never got turned in. The traditional 100% scoring A 90, B 80, etc and all under 60 is an F just never worked for me. Why is everything under 60 failing? And who says 70 is average? Oh, it averages out? Ok, 90% plus 90% plus 0% / 3 = 60% or failing? Not likely. Something must have happened! Thanks for the extra ideas.

You made some extremely relevant points in this post! I especially agree with your point that assessments need to be more closely aligned with the standards. It is so unfair to expect our students to present the information that they’ve so called “learned” in a manner that isn’t representative of how they were “taught.” Thank you for this!

Thank you for sharing! I am still working toward my teaching degree and have yet to begin working in the classroom, however, this is an eye opening article for sure! Grading was not something I had given too much thought until I read your blog. You definitely point out great things to pay attention to. I love the questions you designed. I will definitely same them and use them when I begin creating curriculum in my classroom.

I have been trying to think about grading in a new way since the pandemic started. It really made me think about how I assess student grades. I am so glad I came across your podcast. It has forced me to rethink grading and assessment. Grading should be focused on the mastery of a learning outcome. I also love the picture attached to this titled, “How Accurate are Your Grades? Some questions to ask while planning.” It really puts into perspective what am I teaching? How am I measuring it? Is it applicable? Is it relevant? I’m really leaning more towards standards-based grading this upcoming school year. It is important that I am setting applicable expectations. Thank your discussing this topic. You have provided a great bit of additional resources.

Thanks for sharing, Domonique. Glad to hear this was helpful!

One of the main challenges deals with equity. Will every child have access to all the necessary materials to succeed? I will have to be very careful to not have bias to certain products because those students have access to more resources. It is imperative to focus on the “taught skills.”

There were some excellent resources and viewpoints mentioned that will need to be addressed as we are moving forward in digital learning. Finding the time and specific resources needed in some cases may be challenging to encompass while synchronously teaching.

Great points were made to remind us that when grading to make sure it is for the right reasons. We should make sure that we are grading only on the skills we taught, skills we want students to master and to think about what is important to grade. One of the many great points she made was to do the assignment/project yourself and to model what you expect from the assignment. It’s important to give options when grading assignments- each student learns differently so we should give options- especially in virtual learning- so that students can express themselves using their strengths. Bottom line- make sure we are grading based on skills taught.

This just goes to show how much more work has to be put into remote learning. A simple assessment becomes a big deal to ensure that it is fair to each individual student.

Love it! You argue a good case against so much of what teachers have accepted as TRUTH. Grading policies are one reason I’ve stayed away from the classroom. I support youth with workshops and private sessions, and having eliminated grading is the second best gift that I’ve given to my students and has brought joy to my professional life (first is autonomy). I shake my head at teachers who mark 0 points for a failing assignment worth 100 points. The math here is critical. Please keep talking about grades and outdated, punitive, and illogical ways teachers apply them to learning situations.

Excellent podcast! I am listening from Colombia.

Assuming that students got lower grades for having less access to materials, and writing about it without verifying it is irresponsible.

Very informative and a message that should be revisited at least every 2 years to refocus teachers’ lesson planning/test administering skills

I feel like this should be required listening/reading for all teachers. Great episode!

Glad to hear that the episode resonated with you, Heather!

Learning a great deal, valuable and useful, will listen again and read again, also the additional reading and the links with the downloads are added value.

We’re glad you enjoyed the post.

Good podcast