Listen to the interview with Angela Peery:

Sponsored by Google for Education’s Applied Digital Skills and fastIEP

I’ve been an educator for 36 years, and if there’s one thing I think every educator can agree on, it’s that increasing the number of words our students know is a good thing. Period.

This is supported by decades of research:

- A rich vocabulary supports content knowledge in all disciplines. Conceptual understanding, along with both general and specific word knowledge, impacts learning at every age level, starting with oral language development in preschool. When older students know the meaning of specific words and are able to put related words together during a unit of study, they can connect to new content more readily and remember more (Marzano & Simms, 2013).

- Word knowledge is key for reading comprehension. Kindergarten students’ word knowledge predicts reading comprehension in second grade (Catts, Fey, Zhang, & Tomblin, 1999; Roth, Speece, & Cooper, 2002), and this persists through fourth grade (Wagner, Muse, & Tannenbaum, 2007). Even more surprisingly, Cunningham and Stanovich (1997) find that first-grade students’ vocabulary knowledge predicts their reading comprehension level much later, in the eleventh grade.

- Students who are deficient in vocabulary face numerous obstacles, including having much lower reading comprehension. Their reading range is thus limited, their writing lacks specificity and voice, and their spoken language lacks range of word choice. They risk reading less (both in volume and frequency), not understanding content-area texts or concepts well, writing lackluster essays and reports, and not being able to express themselves as well verbally.

This is why all teachers should address vocabulary instruction head-on.

But what words should be taught? In English language arts/reading classrooms, explicit vocabulary instruction should focus on general academic words (Beck, McKeown & Kucan, 2013). These words cut across disciplines and help students speak, read, and write well in all the academic settings in which they’ll find themselves. In every discipline, there are also domain-specific terms students need to understand and learn.

8 Vocabulary-Building Strategies

Good vocabulary instruction can and should happen throughout the school day. This can happen through incidental learning, when students talk with and listen to others, watch videos, play games, and read independently, through explicit instruction, which are more structured activities, or with the help of digital tools.

The strategies that follow, most of which require very little preparation time, come from three of my books, shown below:

Strategy 1: Informal Conversations

One of the most powerful things teachers (and adults in the home) can do is to have rich conversations with children. Recent research on conversational turns (LENA, 2017) indicates that the more turns a young child takes in conversation with an adult, the more they grow their vocabulary and verbal acuity in general.

So asking questions of a student, receiving their responses, adding information, and asking them to reflect or add more information—in other words, keeping the conversation going—is important in vocabulary development. This idea has great potential for non-instructional segments of the preschool elementary day like snack time, lining up to go to lunch, and restroom breaks. It also has potential for older students.

Strategy 2: Anchored Word Learning

Anchored Word Learning (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2002) is ideal to use with elementary students where read-alouds are typically part of the daily routine. It can also be used in the upper grades, especially with complex text that is being read aloud and discussed together as a whole class.

For young children, picture books provide excellent sources of higher-level, sophisticated words that are important for expanding vocabulary. They expose students to words they would not typically read within leveled books or on their own. For older children, excerpts from novels, nonfiction texts of various types, and content-area texts can all be used for anchored word learning.

Isabel Beck suggests selecting three general academic words each time the teacher reads aloud a picture book or trade book; these should not be esoteric or archaic terms, but words likely to come up in other academic texts. Older students may be able to handle more words during a read-aloud and class discussion, but teachers are cautioned not to select too many words for one lesson. Three to five words is usually sufficient.

Prior to reading, teachers need to complete three simple preparation steps:

- Select a read-aloud. Choose from books by favorite authors, recommended books, new books, old favorites, picture books, trade books, and content-area texts that impart critical information.

- Identify three to five words for direct instruction. Select words which will expand students’ vocabulary and will likely appear in varied contexts—or focus on words critically important to the content being taught. “Nice to know” words don’t have a place here. The idea is to teach important words that are likely to appear in various contexts or words you really want students to know.

- Mark the words in the text with a sticky note or with a highlighter and annotations if the text is on paper.

Once this preparation is complete, follow these steps with students:

- Read the entire text aloud. Don’t stop in the first reading to discuss the words at length. Students need to hear complex texts being read aloud fluently—especially a first reading—so they can start to process the story itself or the complicated ideas present in many nonfiction and content-specific texts.

- After reading the text through once, go back and bring attention to each targeted word. You may want to reread the sentences and/or paragraphs in which each word appears.

- Have students say each word aloud.

- Write each word so it’s visible to students. You may want to have students write the words down as well (or use their fingers and “write” the words in the air or in the palms of their hands). With younger students, spell the word as you write it. Call attention to any interesting spelling feature, such as double letters, silent E, prefixes, etc.

- Provide a student-friendly definition of each word. You may want to repeat this several times.

- Provide examples for each word beyond the context of the text. Encourage children to provide examples of their own so they personalize the word, relating it to their own context. This is a great time to use think-pair-share or turn-and-talk.

- If desired, post these words on your academic word wall. If you’re an ELA/reading teacher, you may want to have a section of the word wall dedicated to words from read-alouds.

Strategy 3: TIP Chart

This adaptation of a word wall features a visual in addition to a brief definition. TIP stands for term, information, and picture. Basically, a TIP Chart (Rollins, 2014) is a three-column poster displayed so students can quickly use it to remind them of the meaning of an important content-area (tier three) word. In essence, it’s a vocabulary anchor chart.

Unlike the well-known Frayer Model, the TIP Chart is useful for words that are fairly straightforward in meaning—not ones with heavy conceptual weight. Once completed, the TIP Chart serves as an “at a glance” reference for important disciplinary terms; this purpose must be kept in mind if the strategy is to be most beneficial.

TIP charts are displayed prominently for the whole class to see, but students can also keep personal TIP charts in their notebooks or digital files as well. The teacher can first model how to create the chart, and later, students can be involved in deciding what information to record and what picture to draw to go with each word.

The best time to use the strategy is when beginning a new chunk of instruction, like a chapter or unit. With the chart ready, announce the first word and call students’ attention to the importance of this word in the current segment of instruction. Write the word in column one. Then share the formal and full definition, which ideally would also be printed in the text or on a screen or board in the classroom. Along with students, from this full definition, develop a short, student-friendly definition or a brief list that you write in the middle column. Do not write the full, formal definition in column two. Lastly, provide or co-create a simple visual in column three.

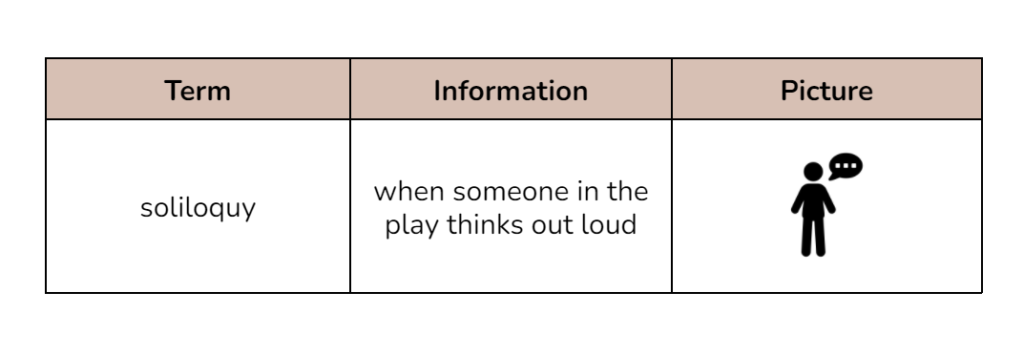

So, for the term soliloquy in my 9th grade English class, I would first give the formal definition: A long, usually serious speech that a character in a play makes to an audience and that reveals the character’s thoughts. We might talk for a minute about the fact that playwrights use soliloquies so the audience understands what a character is thinking. So, in the middle column, we might write the student-friendly, casual definition: When someone in the play thinks out loud. And, to emphasize the fact that this kind of speech is usually given with the character standing alone on the stage, I might then draw a single stick figure with lines or a speech bubble emanating from its face to indicate that he or she is speaking.

The TIP Chart in my class might look something like this:

Here’s a social studies example. For the term “monopoly,” the full definition might be “the exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.” It is assumed that the teacher is also teaching the term “commodity” along with “monopoly.” In column two for “monopoly,” the teacher may write “control of a product or service.” In the third column, he or she might draw a large square that surrounds smaller squares, thus showing the dominance of the one provider. Students might also suggest something that symbolizes a monopoly to them, like an iPhone surrounded by other types of cell phones, but the iPhone appears much larger or more prominent, or the other phones are crossed out.

Teachers can gradually do less in whole-class fashion with TIP charts and encourage students to create their own in hard-copy notebooks or digital notebooks using Google Docs, LiveBinders, or OneNote. Students might preview the first part of each chapter or unit (in any class) and try to complete a personal TIP chart to be kept in their organizational system. They could also collaborate with other students to create TIP charts, so that if any individual is confused about a word, they can get ideas from others. This is a portable strategy students can use with any content area and any textbook from elementary school well into college.

Strategy 4: Save the Last Word for Me

Save the Last Word for Me (Beers, 2003) is an ideal strategy to promote peer conversation, increase engagement, and promote deeper processing about vocabulary and content. Although it’s usually applied to conversations about literature, its clearly defined structure is perfect for reviewing vocabulary and gaining deeper understanding of specific terms.

It is fairly typical for teachers to provide guided review activities before a unit test, midterm, or final exam. Let’s say the instructional unit includes about 25 terms which students must recognize and understand how to use correctly within context. Save the Last Word for Me serves as an engaging vehicle for students to practice doing so in preparation for an assessment.

The steps for employing this strategy are as follows; the first three need to be completed ahead of time:

- Print multiple sets of cards with a target word on one side and the definition on the reverse side (one set for each group of students).

- Print the directions for the activity (see below).

- Place the printed directions and terms in a plastic bag or manila envelope for each group of students.

- Divide students into groups of three to five. It’s important that groups are small so each student has an opportunity to discuss. The goal is for students to review and deepen understanding about concepts and specific terms, so making sure they clarify their thinking aloud is important.

To begin, one student draws a card from the deck and another student defines the term. Moving around the circle, each student adds to the definition, refining and adding examples along the way. The person who draws the cards gets the “last word” and can add to the definition or revise it before students agree upon a definition. You may want to model the process in whole-class fashion first or by having a small group model the process as the rest of the class watches.

Sometimes, if the bank of terms is large, I suggest simply printing one master deck of cards and place five or six cards in each bag. After a few minutes, signal the groups to trade bags of terms and, in so doing, each group gets new terms to review.

While Save the Last Word for Me is low-tech, sometimes simpler is better. It delivers by supporting interaction and engagement, deeper conversations, and higher-level processing.

Student Directions for Save the Last Word for Me

- One student selects a card from the deck and says the term aloud with the other group members.

- On a piece of paper, each student jots down what they know about the term. (This can also be “in your head” and each person takes about 30 seconds to think about what they know about the meaning.)

- When everyone is finished, each person takes a turn sharing their reflections/responses. As each participant shares their thoughts, other students can share thoughts and responses.

- The student who drew the card gets the last word by sharing their reflections/reactions or by stating a fresh view if the responses of others have altered their original thinking.

- If students are unsure or need clarification, they refer to the text, notes, and/or handouts for clarification.

- Another student draws a new card, and the process is repeated.

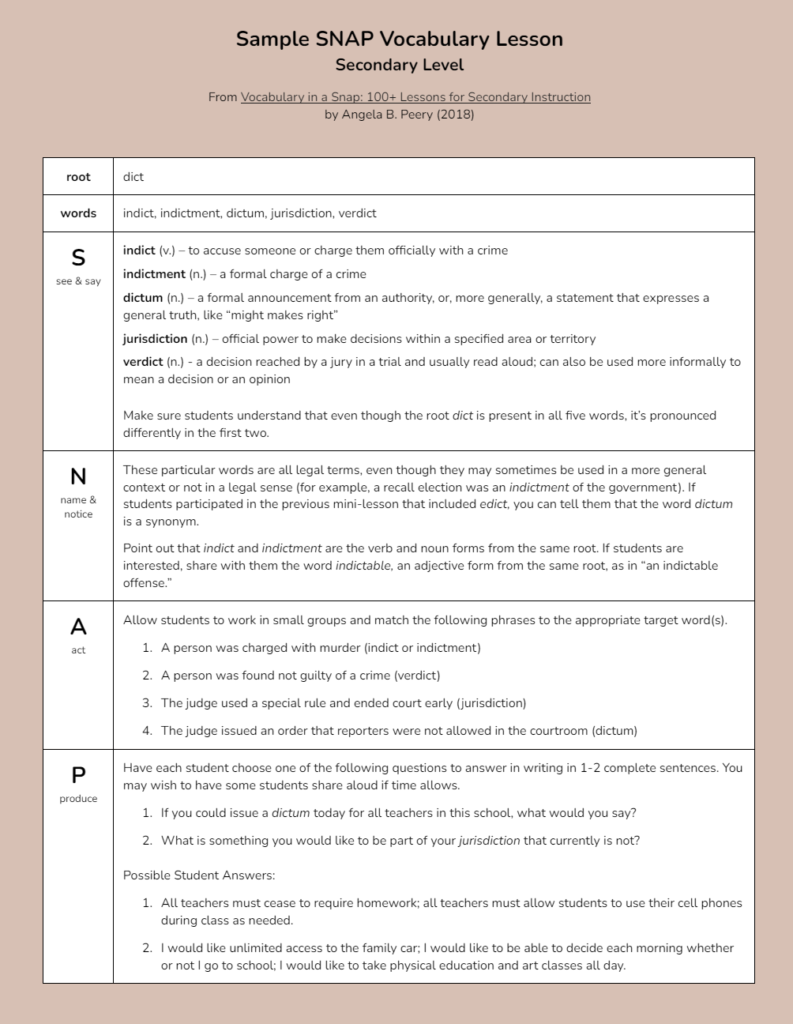

Strategy 5: SNAP Minilessons

Setting aside specific time daily, weekly, or periodically to explicitly teach general academic vocabulary through minilessons (of 5 to 15 minutes each) is another way you can provide explicit instruction.

Each minilesson in my books contains four core components or steps, which the acronym SNAP in the title represents:

S: Seeing and saying each word

N: Naming a category or group each word belongs to or noticing connections to related words or word families

A: Acting on the words (engaging in a brief task or conversation about the words)

P: Producing an individual, original application of the words

The example below is intended for secondary students.

Strategy 6: Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy

The primary purpose of the Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy (VSS) (Haggard, 1986) is to help students generate a list of words to be learned based on their prior knowledge and experience with reading and texts. This strategy can stimulate word growth and independence as students read texts and select vocabulary which they deem important to understanding the content.

VSS includes the following steps:

- Selecting words

- Defining words

- Finalizing word lists

- Extending word knowledge

The strategy can be used to support general word learning from one’s environment or to support vocabulary learning from assigned and self-selected texts.

A colleague of mine routinely used this strategy to support general word learning with college freshmen. Every week, students “collected” three words from their environment (watching, listening, and reading) that they thought important to learn. For each word, students included the following information

- An accurate definition

- Where they heard or read the word including a bit of the context

- A justification for why they thought the word was important to learn

Words were shared and discussed in class at an established time each week. Students also recorded their words in personal vocabulary notebooks. VSS engaged students in lively discussions and specifically raised word consciousness, a critical goal of word learning.

Another way VSS can be implemented is to specifically support word acquisition from content-area text. To support content learning, students can work in cooperative groups and read a chapter from a textbook (or any text). As they read, they identify words they think should be studied and mastered. During class discussion, groups then share their words and why they think the terms are important to mastering content. Additional steps can include developing a class list that contains one word from each group, creating TIP charts with the words, and having students teach minilessons focused on the words to each other.

Strategy 7: Word Talks

Word talks were derived from a similar strategy called book talks, in which students give a brief (less than five minutes) presentation about a book they recommend to their peers for independent reading. Word talks are similar in that they require a student to give a brief presentation on one or several words that they feel are important for their peers to know. This strategy is, like some others in this chapter, excellent for general academic words, not highly specialized, domain-specific words. Also, it can be easily combined with the Vocabulary Self-Collection strategy discussed earlier.

Some teachers who use word talks schedule a certain day a week or a certain day per month on which several students get up and do their word talks. Other teachers schedule a rotation so that a few times a week, one student is doing a word talk that day. Because the word talks consist of a student teaching their peers, it’s important to make time for this, because students tend to find the periods in which their classmates are leading discussion much more memorable than when the teacher is; students often have a way of saying something that “clicks” with their peers just because it’s said in a kid-friendly way.

What kind of words should students share in word talks? Many students share from their independent reading and their media and technology use. Teachers can ask students to provide a rationale for each word chosen if they like, but they can also allow students to share any word that might be interesting. I find myself thinking of the character Sam in the Netflix series Atypical as a high school student. He would have certainly loved to share words related to penguins and Antarctica in word talks.

In a word talk in one of my high school classes, a student selected the following words to share: ascent, descent, decompression, and recompression. Can you tell what the student was learning to do outside of school? Scuba diving. This student was studying for her initial scuba certification and thought these words would be good to share because although they have scuba-specific meanings, they also have application to non-scuba situations.

Word talks are great opportunities for some students to showcase their interests and expertise, but most importantly, they make clear that continual word learning is important.

Strategy 8: Digital Tools for Independent Practice

The following websites/programs offer support for you as a teacher as well as independent practice activities for students:

Flocabulary

This robust program includes hip-hop type videos to help students learn new terminology.

Freerice

This site has an addictive vocabulary game with five difficulty levels, with levels one and two being appropriate for students in grades three and up.

Vocabador

This game allows students to study SAT vocabulary words, choose an avatar, and “get into the ring” to play against other virtual wrestlers.

There’s nothing negative that comes about when anyone grows their vocabulary—and for students, there are many, many positives. By adding even a few of these strategies to your repertoire, you’ll help students build vocabularies that will support them no matter what path they choose to pursue.

References

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Beers, K. (2003). When kids can’t read, what teachers can do: A guide for teachers 6–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Catts, H. W., Fey, M. E., Zhang, X., & Tomblin, J. B. (1999). Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(4), 331–361.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 934–945.

Haggard, M. R. (1986). The vocabulary self-collection strategy: Using student interest and world knowledge to enhance vocabulary growth. Journal of Reading, 29(7), 634–642.

LENA. 2017. Proving the Power of Talk: 10 Years of Research on the Impact of Language on Young Children. Available at https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3975639/Research_Summary.pdf?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lena.org%2F.

Marzano, R. J., & Simms, J. A. (2013). Vocabulary for the Common Core. Bloomington, IN: Marzano Research.

Rollins, S. P. (2014). Learning in the fast lane: 8 ways to put all students on the road to academic success. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wagner, R. K., Muse, A. E., & Tannenbaum, K. R. (Eds.). (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension. New York: Guilford Press.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

Thank you for the tips. Student vocabulary, or lack thereof, has stood out to me since beginning to teach last year. I look forward to applying these in the classroom.

Expanding vocablary in students of all ages is so important. I can modify some of the strategies mentioned to fit my Kindergarten group activities. Purposeful play is an area I see so many words develop and we can expand on them.

I LOVE these ideas! I’m a high school biology teacher. In biology, vocabulary plays a huge role in my instruction. Like I tell my kids, it’s almost like learning another language. I learned early on in my career that just having students write the word and definition has little to no effect on their memory and understanding of the vocab. I constantly fight the memorization trap … “But I memorized the vocab. and those definitions weren’t on the test.”

Thanks for the informative post!

Thank you

Hi Angela,

Your strategies provide a great way to improve vocabulary and literacy levels amongst students while also avoiding the traditional memorization route. I find memorization to be especially detrimental when teaching second language acquisition as students rarely remember the word (largely because it isn’t relevant to them or they haven’t made a personal connection) and at best will recognize it, but not it’s meaning. This really stunts their ability to effectively communicate as they are memorizing pre-determined words/statements or translating words rather than learning them in context.

Do you find yourself ever using these activities as a formative assessment to get a snapshot of student literacy?

I also love the digital resources you have included; a great way to use technology systems to support student learning in a fun and interactive way!

Thanks!

Tai, I think several of the strategies in this post could be used as formative assessments to get a snapshot of student literacy. While some of the strategies are geared toward direct instruction, others would provide great formative data to inform instruction. A few of the strategies that might work well for formative assessment are Strategy 4: Save the Last Word for Me, Strategy 7: Word Talks, and even Strategy 1: Informal Conversation. In addition, most of the digital tools listed at the end of the post have a formative assessment component, as well. I hope this helps! If you do use any of these strategies with students, we’d love for you to let us know how it goes!

Thank you for sharing these strategies! The curriculum I use only provides one vocabulary activity per story, and I know my students need more practice with these words. This helps a lot.

Erica,

We’re glad you found it useful! All the best.