If you’re in the USA and interested in online casinos, check out Full House Clubs’ online casino guide for USA online casinos. Also, explore the thrilling world of poker at BlackChip Poker review.

Listen to an Extended Version of this Post in a Podcast:

Samira Fejzic was used to people saying her name wrong, especially in school. “Through the years, as roll would be called, I would wait for that awkward pause—this is how I knew I was next. I accepted this ritual.”

Fejzic (FAY-zich), whose family left Bosnia in the early nineties and moved to the U.S. in 1999, experienced this ritual for ten years, and she understood that people in her new town weren’t used to names like hers, despite the fact that the area’s Bosnian population had grown massive in recent years.

“It never hurt me until high school graduation,” she recalls. “This was a big day for me. My grandparents from Bosnia came just to watch me get my diploma and of course, my name was butchered.”

If you’re in a position to say lots of student names—in your classroom, over the P.A. system, or especially at awards ceremonies and graduations—no one will be surprised if you mess up a couple of them. But this year, maybe you can do better. If you make the commitment now to get them all right, if you resolve this time to honor your students with clear, beautiful pronunciation of their full, given names, that, my friend, will be the loveliest surprise of all.

Three Kinds of Name-Sayin’

I grew up with a hard-to-pronounce name. Actually, it wasn’t that hard; it just looked different from what people were used to: Yurkosky. (Kind of rhymes with “Her pots ski,” minus the “t” in pots.) Year after year, it threw everyone off. And the way they approached the name put them into one of three camps: fumble-bumblers, arrogant manglers, and calibrators.

The fumble-bumblers I didn’t mind so much. They’d mispronounce the name, slowing down and making their voice all wobbly, not trusting themselves. They’d grimace, laugh, ask me how to say it, then try again. But then they sort of gave up. Over the next few attempts, they’d settle into something that was a kind of approximation, and that would be that. What made me not mind these people was that they put the mispronunciation on themselves—their demeanor suggested the fault was with them, not me or my name.

The arrogant manglers were another story. They assumed their pronunciation was correct and just plowed ahead, never bothering to check. In many cases, an arrogant mangler will persist with their own pronunciation even after they’ve been corrected. Adan (uh-DON) Deeb, whose family hails from Israel with Palestinian roots, experienced this as a middle school student in the U.S. “Every time I was called up to the office, EVERY SINGLE TIME, they would mispronounce my name, no matter how many times I corrected them. It made me angry. To me that shows that they just don’t care enough to get my name right.”

This group has a couple of sub-categories: One is the nicknamers—people who come across a name like Rajendrani and announce, “We’ll just call you Amy.” The other is the worst kind, the people who start with the first syllable, then wave the rest of the name away like so much cigarette smoke, adding “Whatever your name is,” or just “whatever.” I don’t have a creative name for this group. Let’s just call them assholes.

Finally, there was a small group I think of as the calibrators, people who recognized that my name required a little more effort. They asked me to pronounce it, tried to replicate it, then fine-tuned it a few more times against my own pronunciation. Some of them would even check back later to make sure they still had it.

My cousin Laura, who has the same last name I grew up with, remembers a professor who was a true calibrator. “It did take him a bit of time to learn to pronounce my name, but he was always apologetic when he said it wrong, and always insisted on the importance of getting such things right. He was easily the most inspirational and challenging teacher I’ve had…he just insisted that every student feel important.”

If you’re already a calibrator, keep up the good work. If you’re not—if you’ve let yourself off the hook with some idea like “I’m terrible with names”—know that it’s not too late to turn things around, and it does matter. Though it may seem inconsequential to you, the way you handle names has deeper implications than you might realize.

Kind of a Big Deal

People’s reaction to this issue varies depending on their personality. If your student has a strong desire to please, wants desperately to fit in, or is generally conflict-avoidant, they may never tell you you’re saying their name wrong. For those students, it might matter a lot, but they’d never say so. And other kids are just more laid-back in general. But for many students, the way you say their name conveys a more significant message.

Name mispronunciation – especially the kind committed by the arrogant manglers—actually falls into a larger category of behaviors called microaggressions, defined by researchers at Columbia University’s Teachers College as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (Sue et al., 2007).

In other words, mutilating someone’s name is a tiny act of bigotry. Whether you intend to or not, what you’re communicating is this: Your name is different. Foreign. Weird. It’s not worth my time to get it right. Although most of your students may not know the word microaggression, they’re probably familiar with that vague feeling of marginalization, the message that everyone else is “normal,” and they are not.

In her piece What’s in a Name? Kind of a Lot, writer Tracy Clayton (under the name Brokey McPoverty) rails against Ryan Seacrest’s move to shorten the name of actress Quvenzhané Wallis to “Little Q.” She points out that Seacrest and other media figures treat the names of some actors—who happen to be white—differently: “The problem is that white Hollywood…doesn’t deem her as important as, say, Renee Zellweger, or Zach Galifianakis, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, all of whom have names that are difficult to pronounce—but they manage. The message sent is this: You, young, black, female child, are not worth the time and energy it will take me to learn to spell and pronounce your name.”

This, by the way, is how you say Quvenzhané:

This issue goes beyond names rooted in cultures unfamiliar to the speaker. Whatever it is your student prefers to be called, it’s worth the effort to get it right. I’m sure I’ve not only mispronounced my own students’ names, but I’ve probably also called them something that was not their preference—realizing in April that the kid I’ve been calling Stephan all year actually prefers to be called Jude.

And before you get all defensive about the bigotry thing, let’s be clear: Discovering that something you do might be construed as bigotry doesn’t mean anyone is calling you a bigot. It’s just an opportunity to grow. An opportunity to understand that doing something a little differently shows others that you respect them. At some point in your life, someone probably taught you to hold the door open for the person coming in behind you. Before then, maybe you didn’t know. Opportunity to grow. It’s that simple.

How to Get it Right

The best way to get students’ names right is to just ask them. Pull the kid aside and say, You know what? I think I’ve been messing up your name all year, and I’m sorry. Now that graduation is coming, I want to say it perfectly. Can you teach me?

By humbling yourself in this way, you let them see that you’re human. You’re modeling what it looks like to be a lifelong learner, a flexible, confident person who is not afraid to admit a mistake. Regardless of the outcome, a genuine effort on your part will mean so much, and when the big day comes, they might even root for you to get it right.

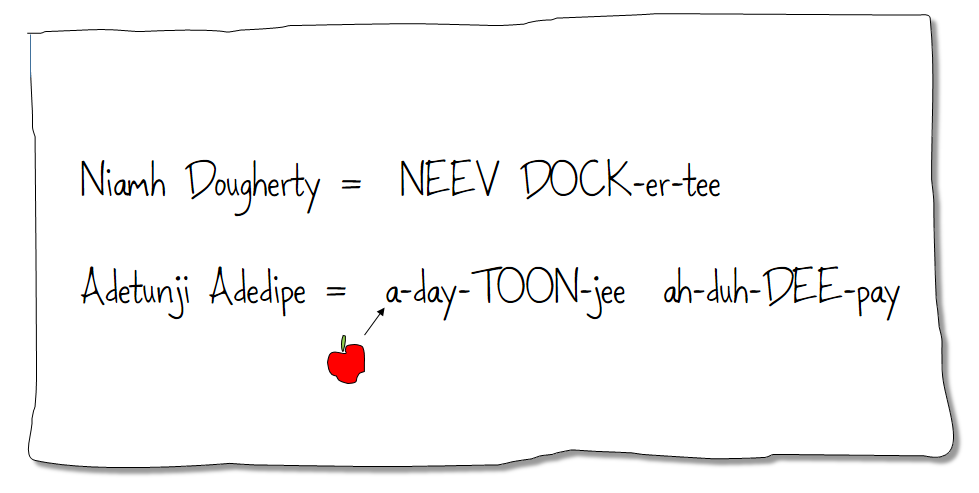

If you have hundreds of names to learn, get systematic: Starting now, carry around a clipboard with all the names you’ll need to say – even those you think you already know, and start checking in with kids in the cafeteria, in the halls, in the stands at a basketball game. And for God’s sake, write down what they tell you. When the big day comes, the page of names you read from should look something like this:

Do whatever it takes, using whatever kind of symbols or notes you need to get the right syllables out in the right order. (The apple is there to remind the speaker to say that “a” like they would in the word apple.)

If you’ve run out of time to ask students themselves, or if doing that is too uncomfortable for you, you can get some help online. On Pronounce Names, you can find a huge collection of names and their pronunciations.

Whatever you do, do something. For some students, you may be the first person who ever bothered. If the only time you say their name is in the classroom, your correct pronunciation will help the whole class learn it, too. Eventually that will ripple through the school, making that student feel known in a place where before they felt unknown.

And if you have the honor of announcing them on the day they receive their award, their diploma, the day that marks some big achievement, you have a unique opportunity to make it even more special, but you only have two seconds: Make it count. It’s a gift they’ll remember for a long time. ♥

Reference:

Sue, D.W., Capodilupo, C.M., Torino, G.C., Bucceri, J.M., Holder, A.M.B., Nadal, K.L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62 (4), 271-286.

Join my mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration — in quick, bite-sized packages — all geared toward making your teaching more effective and fun. To thank you, you’ll get a free copy of my new e-booklet, 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half.

The mispronunciation of names can be very frustrating and embarrassing. During role call, whenever there is an awkward silence, I know that my name is next so instead of listening to my name being butchered, I usually relieve the person from saying my name and say it myself. Nobody likes to hear their name being pronounced incorrectly, but unfortunately as a teacher, I have been guilty of mispronouncing my student’s names. Being a foreigner myself, instead of teaching people the correct way to say my full name, I either shorten it or make it easier for both them and me by changing the pronunciation of my name to meet their needs.

Thanks so much for sharing this. Was there ever anyone who really made an effort to say your name correctly? If so, how did it feel to be on the receiving end of that?

Though I understand what you’re saying and there is definitely truth to it I’ve always taken a different viewpoint on this issue. I’m a white German girl who’s hippie parents gave her an unusual hawaiian name that no one can pronounce or spell. Though it was hard as a child when I grew older my opinion changed. The definition of politeness is making those around you comfortable so I simply shortened my name to something that was easy for everyone. It’s just as awkward for the other person trying to say your name so just let it go and don’t hold onto your indignation so strongly. My father’s name is Bryan, when we lived in Mexico he went by his second name David because it was easier for the people there to pronounce. Step off your high horse once in a while and just make it easier for others…your family and friends will still always get it right and that’s what really matters.

DO NOT bow down and shorten your name. You name is beautiful, unique and your name which is who you are. Teach them how to say your name. People mess up my maiden name and I make sure they pronounce it correctly. I take the time to say your name correctly, give me the same respect.

I agree 100% with you. Names are important. I teach teens and they can be a little self conscious to correct the teacher. I always try persist to make sure I learn their names by gently asking them one on one to teach me ( so they don’t feel on the spot in front of peers). While my name is very popular here in Canada, my husband’s isn’t, so I usually tell the students about the time I tried to reach my husband at work because of a family emergency. Unfortunately, he’d never corrected the mispronunciation of his name so when I asked to speak with him – the receptionist had no clue who I wanted to speak to. It took us several minutes to sort out who I was asking for. Finally, she corrected my pronunciation of his name! Needless to say it was silly and frustrating waste of time when I really needed to talk to him. After that, his coworkers made a point to learn his name though.

This also happened to me–my husband’s co-workers of 1-9 years could not be bothered to learn how to pronounce his 2-syllable name–they called him “G.” So every time I called for him, I refused to call him “G” but pronounced his full name–it took them a while, but they always managed to figure it out–“Oh, that is “G.” Then I would gently say–his name is G—–, and please learn to say it.

I agree that there are far too many people who do not make an effort to pronounce names right, and that this is indeed frustrating and needlessly makes the person feel undervalued. However, it is important to keep in mind as well that some people have hearing issues, speech impediments, their culture does not have a particular sound, or quite frankly has never been exposed to some multi-cultural names. These things make getting the pronunciation difficult. Many rush through it because of their own feelings of inadequacy (tell me a roster of names you have no idea how to pronounce is not intimidating). Some hem and haw from straight embaressment, not necessarily because they are trying. Others try very hard but just can’t do it. (If I had to roll my r’s to save my life – I’d end up dead, lol).

It is also easy to revert back to a misproununciation in my experience, because of the automaticity of language; sometimes phonics just takes over and it takes a second to realize the rules you grew up with don’t apply here – just take a moment to forget everything you ever learned about reading and pronunciation, and try again. I say this jokingly and without malice, but if that learning has truly been ingrained, it takes awhile to retrain your brain. It is especially fun when you have two names spelled the same way and prounced differently – ugh! Its not that I’m trying to be rude – and I usually correct myself, but my initial reaction tends to go with what is most mainstream or what I’ve been taught.

I once had a student who told me every day I did not pronounce his name correctly. He berated me and was very rude about it. I could not hear a differnce between what he was saying was the correct pronunciation and what I was saying. I honestly thought I was saying it correctly and he was just being an ass and finding it funny to bully the teacher. I literally was broght to tears a couple of times. A few years later, I was volunteering at church camp and we had a missionary from his country there. I asked the missionary about his name, and the missionary laughed. He said I was indeed buthchering the name, but not to fret, because very few Americans could tell the differnce. We didn’t have that sound in our language, and the slight clicks were very difficult to detect. He verified that the student most likely knew this and thought it funny to bully me.

So while it is nice to have your name pronounced correctly (for as simple as mine looks, it is usually pronounced incorrectly, so I get it), it is also just as important to view the issue from both sides of the coin. Just like putting in a true effort, understanding, kindness, and forgiveness go a long way too.

The mispronunciation if names during big occasions really bothers me. Most names in my district are rather easy to read, leaving just a few the speaker has to learn. I’m sharing this with our would be presenters in the hope they will try a little harder. As an aside, I had a student named Adetunji Adedipe a number of years ago. Is it a common name?

People who pronounce your name wrong usuaully ar enot doing it on purpose but it still hurts

My last name is only 5 letters long, but I hear it said and see it spelled a shockingly varied number of ways.

Oh, and my family has been in the US since the late 1600s. So I literally could join the Daughters of the Revolution, but most Americans I meet side-eye my last name. It’s fairly common in Lancaster by my research. So I’m even more proud to be the first bachelor of science grad in my immediate family, because maybe people outside of the Pennsylvanian Deutch community will learn something new, and reflect that “weird names” is a bull sh*t concept.

In my youth, I was actively involved in 4-H, swim team, and many other activities. One time my name was in the same local newspaper 13 times. Every single time my name was spelled a different way, and not one of them (both first and last name together) were correct!

As a long-time teacher, I never allow a student to shorten his/her name or allow it to be mispronounced, unless they actually PREFER to be “Chuck” rather than Chukwenyere, for example. I do not allow other students to mutter a name, stumble and then say “whatever.” I let the person named drill us with the actual pronunciation. For me, I ask again as many times as it takes me, and write my own version of the IPA symbols in my record book so hopefully I can do it right the rest of the term. This, to me, is not harder than learning to pronounce the long Latinate medical terms, or the names of Egyptian gods or manga/anime authors.

Many schools now ask students to write out how their name is pronounced on those graduation name cards–this helps.

Wondered onto this blog after a Facebook friend posted your double space between sentences post. This post reminded my of my first day in HS (student). The gym teacher read the class roll from an old dot matrix printout. Kid in my class, Frederick C., had his name print out as Freder. Mr. M (gym teacher – a certified jock) called him Freder for the next 4 years. Of course we ALL called him Freder after that, even though we knew him as Fred all through elementary school. To his credit, he thought it was funny and would introduce himself as Freder once in a while.

I have simple, common name: Farrell. (Rhymes with barrel.) Simple, right? It boggles my mind how many folks pronounce it “fur-RELL.” Sigh.

Interesting blog, even for a non-teacher and murderer of the English language. Please pardon the double spaces between sentences (old guy). You should see what I do with semicolons.

Ooh! I remember my last name being butchered so often I forget this one of my first name:

Elective: required for graduation –

Health

Me: 16 year old high school junior, in the school district ~6 years.

Substitute teacher: reading names from the spiral-bound gradebook, getting ever more loud and angry with the lack of response for the first name. Class was mix of juniors and seniors.

We the class: looking around at each other asking “wait who?? I don’t know who she means! Help!! Do you know?”

Me: hearing her move on to shouting the next name: “Janelle. JANELLE. Janelle , you better answer or I’ll write you up!”

Me: “umm…. Dani ?”

Sub: visibly shocked and annoyed. “Your regular teacher has a very loopy D”

Yeah, I’m sure that would have went down the same if she knew it were a D all along…

Good for Freder for having a sense of humor! Names are important, but so are nick-names. Maya Angelou (Margarite Johnson) and Bones (Jim) MacKay come to mind.

this discussion reminds me of advice That Father Greg Boyle, (also know as G-Dog) got on his first day of teaching: from a veteran teacher:

“Two things,” she says, “One: know all their names by tomorrow. Two: It’s more important that they know you than that they know what you know.”

― Gregory J. Boyle, “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion”

This is so important! Nearly 3/4 of the students at my school are Hispanic, so pronunciation should not be such a mystery. I tell teachers, “Taco. Burrito. Quesadilla. Now you know how to pronounce Spanish vowels. They never vary.”. Yet in every award situation, many of the names are mangled.

More important, most kids clearly believe they have no right to assert themselves over the way they want their names pronounced. Every time I ask someone — even an adult — “Do you like to be called Diana or Deana?” I get a surprised look.

I believe that everyone can learn to pronounce (almost) everyone else’s name correctly, and that making the effort is the first sign of respect. For a teacher not to even try to learn a student’s proper name is saying either “I can teach but I can’t learn, or at least not if something requires practice,” or “Knowing your true self-identity is not very important to me.” That sounds harsh and will annoy a lot of my wonderful teacher friends. I don’t think they intend either of those messages, but the message gets across anyway.

Yesterday I had a conversation with a new parapro at my school. I asked his last name so I could introduce him to my class. He said, “It’s Tesoro, but that’s kind of hard so they can call me Mr. T.” I went over and whispered, “Some people enjoy having a nickname that kids call them, and that’s fine, but don’t ever tell kids that your name is too hard for them to say. You’re telling them, ‘I don’t believe you can learn from me.’ Tell them, ‘Here’s my name. Try saying it 3 times and you’ll get it.'” My class mastered the Greek name of one parapro in about 30 seconds: “Kat-a-po-des. Kat-a-po-des. Katapodes.” And Kindergartners I barely know enjoy saying to me, “Hi, Ms. Hokanson!” Why? Because using a name has power, it establishes a special connection between the speaker and the spoken to, and KIDS KNOW THIS.

“I can teach but I can’t learn.” That’s powerful stuff. We talk a good game about being role models for our students, about being “lead learners.” It’s not often enough that we get authentic opportunities to put our money where our mouth is, but learning unfamiliar names is definitely one of them. Thanks for pointing that out.

LOVE that you mentioned teachers’ names here: Far too often we allow our students to avoid getting OUR names right. Regardless of how it’s spelled, every name is ultimately just a collection of syllables that can be repeated and remembered. Teachers should model this process with their own names and take the extra time to show students how to pronounce them correctly.

And you’re SO RIGHT about the special connection between people who use each other’s names correctly. Although this article scolds those who don’t make the effort, what I want to convey even more strongly is what a tremendous difference it makes when you DO make that effort. I think a lot of kids have just gotten used to having their names mispronounced…so it’s pretty special when someone actually takes the trouble to get it right.

As a substitute teacher, I have witnessed a student’s face light up when I get their name right the first time. When I see a name I’m not sure of on the attendance list, I often pull a student to the side to clarify the pronunciation. I make a lot of mistakes, but believe it’s important to try and try again.

Thanks for the insightful read. I like to think of myself as a calibrator, but I am sure I fall far short of the optimum. I admit to my 400 freshmen, every term, that I might butcher their names, and to correct me if I am wrong. However, I am more bothered by those student who, for whatever reason, find it necessary to try to correct my surname to fit their mindset, as some are native Spanish speakers. After 5 generations, we pronounce the name in American English, not in the language of the old country: Floor-ez, not Flor-e’ss. I am not a Spanish speaker, however, because I have dark skin, there seem to be presumptions. Some students even will walk out of the first class, and drop the course, because I am not what they might think I should be. -Dr. M

Hi Dr. M.

I wonder if these students are working under the assumption that they are being respectful by pronouncing your name with the original Spanish pronunciation. If nothing else, thinking of it this way might bother you less.

That was my thought, too, that these students were actually being very respectful.

Also, representation matters. Minority students may be excited to have a teacher/professor with their nationality. It seems odd someone would leave a class or drop it after one session simply due to a name pronunciation or not being Hispanic/claiming the Hispanic background.

Well done Jennifer. This is something that really affects a student’s motivation and self concept but its rarely brought up in any teacher training or school culture meeting. I myself have had the same issue with my maiden name (Schultek: sh-uhl-tek). It is rarely spelled right or pronounced correctly. As I was listening to your podcast, I loved that you named the type of responses when mispronouncing a name and it made me think about my own experience. Fumble Bumblers is probably the most often response, yet not a drastic offense to me. However, I have seen numerous leaders become ‘microagressers’, as you mentioned above. The look on a child’s face when there is no desire to show respect for one’s identity, because that is what is happening here, is heartbreaking. I know I am not perfect in saying some names, but I am much more aware due to your post of how I respond when I do get it wrong. Do I push through and move on? Do I ask to be corrected or validated? Do I rename them? But more importantly, how do students respond when I am incorrect? Do they slump? Do they look downward? Do they retreat for the rest of the day? These clues will better help me know how I am being perceived. Thank you for helping me be reflective today, and opening my eyes to my non-intentional potentially hurtful mispronunciation of student’s names.

Thank you, Gretchen. I’m so glad to hear this resonated with you!

I have an incredibly easy name so I’ve never had to deal with pronunciation issues BUT the connection you make between a student’s name and their sense of identity speaks to me. On the flip side of unusually names we have really, really common names so I have to ask: Have you ever encountered the issue of having two children with the same name in one classroom? If so, how did you handle it?

My name is Jessica and where I live it is the most common name for girls my age so I ended up in quite a few classrooms with other Jessica’s. (One time I went to a summer camp with three other Jessica’s) Some teachers handled it with grace by either incorporating last/middle names or just by placing us Jessica’s in different areas of the classroom so a gesture or look could easily indicate who they were speaking to. Other’s didn’t do as well saying there was a “Jessica” and a “Other Jessica”. (Sometimes I was “Jessica” other times I was “Other”) However, the worst was this one teacher that gave an ultimatum. One of the two Jessica’s had to change our name to a nickname. Neither of us wanted to do it, but the other Jessica was more stubborn than I was. The teacher automaticly started calling me Jesse and my only way to exert control was to tell her I wanted it to be spelled Jessi. It was awful! It made me feel like she was saying “your name is no longer convenient to me so you need to change it.” It was like that for almost the year until “Jessica” moved and then I had to go through trying (and failing) to get everyone to call me Jessica again.

After that I automaticly co-sign any and all things about names being important. Names change how we feel about ourselves and trust me being outright called “other” is not a super way to start identifying yourself.

Jessica, thank you for adding this story. This issue goes far beyond names that have a more “international” flavor and can come up in situations as simple as two students having the same name. As a Jennifer who grew up in the 70’s and 80’s with millions of other Jennifers, I was fortunate to never experience anything like the situation you described. We just always added our last initials and our teachers, thank goodness, were satisfied with that. How disrespectful–to force you to change your name! Anyway, thank you again for contributing to this ongoing conversation.

The worst thing was I was Lisa and there was another Lisa in the class. Once he asked “Lisa” and someone asked “Which one?” and he said “Little Lisa” indicating me because the other Lisa was overweight! He only did it once- but it really must have hurt the other Lisa a lot.

My last name is Italian, but it is only 3 syllables and not all that hard just to read slowly and say it right but so many people have added 2 extra syllables. Instead of Con-tor-no they get Bon-tor-reen-ee-o. Or Con-tor-nee-o I never could figure that one out! I would think the best thing is to read the name slowly and one syllable at a time instead of freaking out and just screaming out a bunch of similar sounds in any order.

As a Jennifer of the 80s/90s we had 5 Jennifer’s in our grade 8 class. We went through all the permutations of the name (Jen, Jenny, Jennifer,) but 2 of us shared the same last initial. We chose to go by our last names instead of having to write out our full name every time. To this day some of my grade school friends still refer to me as Flanders and my friend as Fitzy (I believe her last name was Fitzsimmons). When choosing my children’s names we made sure to pick easy to pronounce but unique names.

As an educator I love the page https://www.mynamemyidentity.org it includes a pledge to pronounce students names correctly and support their identities.

This is one of the main reasons our team came up with http://www.nameshouts.com. We recognize how international borders are becoming less and less important. To each individual, their name is one of the most important parts of their identity. It’s a real shame that people do not try harder to pronounce names the way they are meant to be pronounced.

A story from our two-way bilingual third grade classroom

It’s Tuesday morning in our two-way bilingual third grade classes. Eramos de una visión…la música de su corazón is playing softly as the children write in their morning journals. Ramona Mejia, my teaching partner, and I are talking about the day in the doorway between the Spanish and English classrooms. Then it is time for morning circle. The chékere–a beaded gourd instrument calls us to order. Each child says their name and the group responds and echoes. Echoes of names bounce back around the circle as we play the whispering name game. Yismilka/Yismilka, Rodney/Rodney, Maria/Maria, Frederick says Federico with a nervous smile. The game stops. Federico has changed his name over the long weekend.

“Federico, let me tell you a story of how I lost my name in third grade.” I tell Federico and the class this story:

My name is Berta… Berrrrrr-ta. I was born in La Habana, Cuba. When I was in third grade my family moved to this country. I spoke no English. The folks at the school spoke no Spanish. Sadly, not one my twelve blond, blue-eyed, third grade guardian angels could say Berta. “Bbbbbbb-eeeeee-rrrrrrrrrr … como tren, ferrocarril, tigre: rrrrrrrrrr …” Not one. I decided that I had to teach my new classmates how to pronounce my name. I gave lessons during recess and after school. I recited the rhyme: “Erre, con erre cigarro, erre con erre barril, rapido corren los carros sobre las lineas del ferrocarril.”

The teacher told me that I must change my name to something Americans could pronounce easily: Bertha – but there is no thuh sound in our Spanish. We are Cubans, we are not a colony of Spain, we do not use the royal lisp. I had to practice th-th-th-th, and discovered, instead, zzzzzz – another sound not found in Cuban Spanish.

At lunch, the second week of school, I eyed the tray of grilled American cheese sandwiches and the white milk without sugar – food I could not eat. I was gagging at the prospect of swallowing that bland white stuff all at once – the food stuck in my throat, like the name they wanted me to adopt: Ber-thz-thz-thz… Ber-zzzz-a. Not my name, not my name! I lost my name, my spirit.

Frustrated and disappointed, I compromised by calling myself “Bert” while reluctantly answering to “Bertha.” Without the support and encouragement of teachers and other adults it took me ten years to reclaim my name, and with it, my Cuban identity. But at 18 years old I declared, proudly, for all to hear: ¡No! Me llamo Berta. ¿Te gusta? Berta. “So Federico, I tell you this story so that you never give up your name. Keep on, Federico! Federico “ we whisper back.

The ritual call and response of names settles. Others around the circle share stories about their names, nicknames and namesakes. Miguel was named after his father’s favorite uncle. Marilyn was carries the name of her great grandmother who was an important matriarch. Kevonia was called Kiki by her sister and now everyone calls her Kiki. Joshua has carrying his father’s name and his sister their grandmother’s name who is still in Puerto Rico. Each name is a thread on the weave of the family heritage regardless of the immigration route.

Thank you so much for taking the time to share this, Berta. It’s beautiful and shows all teachers a thoughtful and lovely way to honor our students’ names.

When I was in the 3rd grade my teacher kept mispronouncing my name. I started calling her by the wrong name. When she spoke to my mother about my inability to remember her name my mother said, “If you get her name right, maybe she will remember yours.” It worked. My name is not difficult to pronounce, it just doesn’t match English phonics. – Maile

I love this!

I had a supervisor for a 5 month period who INSISTED on correcting MY pronunciation. It angered me every time. Believe me, I do know how to pronounce the last name I married into.

One type of person you forgot was the “douchebag.” This is the person who has snide comments about someone’s name, judges a person because of their name, and/or corrects someone in pronpunching their own name.

Ah yes. I overlooked that person completely. Thanks, Candy. Now we have the full picture. 🙂

On the first day of class, instead of me calling roll, I go around the class and ask each student to pronounce their first name and last name, and any nickname that they want to be called. I write it phonetically on my seating chart. Much better than me making an idiot of myself and better for the student to hear the name pronounced correctly.

This is genius! As someone gets her name mispronounced every single day, I’m hyper aware of the importance of getting it right.

So what is it when students (on purpose?) mispronounce the instructors name? Is that, too, considered to be microaggression? I try really hard to pronounce my student’s name correctly and I don’t mind being corrected (having to learn 90+ names every 16 weeks)…and they can’t take the time to learn mine.? ALSO: I have earned a PhD and I am still called “Mrs.”- I understand *microaggression*

I think that’s the difference between a child and an adult. If you’re modeling the effort to get a name right, that will make an impression on MOST of your students. Just like so many of the other behaviors you demonstrate, they will rub off. For some kids, maybe not for a very long time, but it’s worth it for you to keep being a positive role model. I’m curious, though–how do you know they are pronouncing your name on purpose?

I teach at a community college.We do have some duel-enrolled students. And I am pretty sure that they are doing it on purpose when they laugh after it (and not in an embarrassed way) – and I have also pronounced it to them MANY times.

Of all my titles, Mrs., is the one to which I am the MOST honored to be referred, Doctor Kleber!

Giving your child an unpronounceable name is the true “microagression.” I always have prided myself on my efforts to get names down. My biggest struggle came with the French names at a school in Louisiana. However, those with difficult names must recognize the struggle people face and, as many Asian cultures do, actively assimilate to the culture they are trying to be successful in. It would be a disservice for teachers to shelter and coddle students and build for them a false expectation that their identities are wholeheartedly embraced when they aren’t.

Unpronounceable is in the eye of the beholder. “Difficult” is subjective. And the effort to pronounce a person’s name correctly tells the world a lot about character of the person speaking, regardless of the name they are trying to pronounce. I’m glad you have make that effort; what’s unclear to me is why, if you have always prided yourself in those efforts, this would offend you so much. The effort is what matters. But the view that a particular name is “unpronounceable” is where you lose me; syllables are syllables. As a northerner who has lived in the south for 15 years, it still baffles me how many people in this region simply can’t get the word “Massachusetts” out right. Did that state get a difficult name?

This really hits a nerve with me. My name is Paula. I am of Italian background but I grew up around both Spanish and Italian speakers so I do not mind if someone calls me Paola. However, my name is Paula (pronounced as a Spanish speaker would say it). Because I used to be a Spanish professor before making a shift in career to Chinese medicine, I spent my entire adult life until now being called by my correct name. Now, though, I am in my final year of a TCM program and in this new life, people cannot be bothered to even TRY to pronounce my name correctly most of the time. I hear them say this name that is not mine and think: “If you had a patient named María, would you look at her chart, look up and say brightly, “Hi, Mary”? No, this would not happen (I hope). So why is it ok to call me Pah-lah when I clearly said that my name is PaULa?” And I know that there is a lot going on in this world and that my name is a small thing in comparison, but it is my name. Sometimes I feel invisible when people call me Pah-lah, and I am an adult, multi-lingual, and highly-degreed. I can only imagine the shame a child would feel, and then sense of hurt, if nobody could be bothered to even TRY to pronounce his or her name correctly. A person’s name is important. And just because it looks familiar to English-speaking eyes, that does not mean that it is an American or English language name. So yes, this article hit a nerve with me. Thank you for writing it.

I guess, perhaps in your new field, people read your name and see Paul followed by an A. They may be doing Paul-ah. Perhaps, in the past people first heard your name never read it. Maybe among a group used to hear names in many languages, (if they were Italian and Spanish the differences are in the emphasis not in the sound of the vowels) and perhaps now you are confronting people with saxon roots, languages that pay more attention to the consonants than the vowels. I’m Spanish, and if i see Mariah my first natural reaction is to say Maria. I realized, I “read” names, i don’t repeat sounds. In my brain, the h is silent and doesn’t change the sound of what is ahead of it. It takes a lot of cognitive effort to get that name right.

Thank you for this. As someone with an uncommon (at least it was relatively uncommon when I was born in 1965) Irish Gaelic version of a fairly common Germanic first name, I can relate to this. My first name is two syllables. Lee-Um. It is not Lie-am and I am not named Lee-On. Lee-Um.

You would think people would have gotten that by now, but you’d be surprised at how many people evidently don’t even bother to get it right.

But now that there is a famous actor (Liam Neeson) who shares my first name, when people ask me how I pronounce my name, I will either say “Correctly” (the snarky answer) or I will say “Just like the actor” and if people still don’t understand, I will say his name.

By the way, the best way to ask me how I pronounce my name is not “How do you pronounce your name?” but rather “What is the correct pronunciation of your name?” if you ask me the first question, after a lifetime of people mangling my name and/or not hearing it correctly, I am sorely tempted to give you the snarky answer [“Correctly”] rather than the helpful answer because the first form of the question, while trying to be ‘helpful’ is really just laziness on your part. Don’t ask me how I pronounce my name. Instead, ask me how it is pronounced correctly and I will tell you.

I also used to get a lot of teasing and crap from my schoolmates about my name, so yes, I am kind of sensitive about this topic.

You should get over the question “how do you pronounce your name?”Just appreciate that people are asking. I was watching a YouTube video of a news announcer (Cenk Uygur) explaining how to pronounce his name. In the comment section there were people correcting the news announcer about how to pronounce his own name! So I think the question “how do you pronounce your name” is a perfectly acceptable question, because other people may decide to pronounce it differently and tell you the way you’re pronouncing it is wrong.

I teach in a school in the southenr suburbs of Johannesburg (resulting in kids from up to 15 different ethnicities in one classroom). Our indigenous languages share sounds, so as long as you know how the letters in a childs name translate into sounds, you’re golden. I can pronounce any local child’s name without a problem. But my principal, HOD and others can’t and don’t even bother trying. At an awards evening, the principal mangled one child’s name three different ways. I wanted to strangle her. The child’s name was Ikageng Ramphomane (Eek-uh-hhh-eng Rum-poh-maan-ee). The kid’s surname was pronounced Rum-oh-maan-ie, Rum-FFF-oh-maan-ee and Rum-paaah-mane. I wanted to scream, how have you worked at this place for decades and still can’t say the sounds?!! They’re not hard. I figured them out in my first year of teaching!

I became a calibrator though a baptism of fire when I spent a year in Taiwan as an English teacher after college graduation. Since then, I have become a professor and teach on a very diverse university campus, which forces me to update and hone my skills.

My personal beef is with my youngest daughter’s name, Mikaëla. Most Americans use Makayla (or any of a host of variant spellings), blasting through that diphthong to make a three-syllable pronunciation. This is understandable, since English typically does not split diphthongs; hence the use of the umlaut over the e to prompt a four-syllable pronunciation. This is how it is done in French and Spanish (which I speak). It is very difficult to get teachers and parents to say it correctly however, though classmates usually pick it up instantly. I think another group, or perhaps a subset of “arrogant manglers” could be “the inveterately lazy.” These are people who have already decided how they will pronounce a name, often before they finish hearing it the first time, like a kind of autocorrect function. To learn better is an unreasonable call on their time and energy.

It almost seems that sometimes adults pronounce the names like the four syllable Mikaëla as the three syllable Mikayla as a ‘lesson’ or correction to the child’s parents for ‘getting it wrong’ or being ‘difficult’ by choosing such a name for our children. As in, your parent named you something unusual/difficult and we are going to mainstream you instead of honoring the individuality of the lesson and the honor of the name bestowed on them.

To bad if your name is of San origin and !Kung language

I really appreciate the teachers who do take the time to get every students name right especially in large classes right from the start so they have the entire semester to start to getting it right. I had a philosophy professor who was very dedicated to getting his students names right but perhaps it was because he had a different last name that must have been butchered this his life and never wants that to happen to his students. I hope more teachers can be like him.

When I worked for the Open University in London, we spent a lot of time phoning students before the degree ceremony to make sure we pronounced their names right. London, of course, has a population of all nationalities. I was on jury service once, the old-fashioned judge just would not get the defence counsel’s African surname right, though it was quite phonetic. I thought this was very arrogant. Luckily I have a “feel” for language, but I do know people who just can’t remember pronunciation (the “bumblers”). But others seem to think that having a name that doesn’t sound typically English is pretentious! It’s also an English vice to think that pronouncing foreign names or words properly makes YOU pretentious; people on Facebook were making fun of a mother who was teaching her child to pronounce quinoa.

I’m amazed by how in the UK, people pronounce the names in the mother tong pronunciation of the person named. They shock me when at the coffee shop they call me Rafael and not Rafiil or Ralph or Rah-phee-el, as it happens in the US. But most shocking are sport commentators pronouncing the name of the uruguayan soccer player Coates not as rhyming with “coats” but Co-ah-tes, as it is pronounced in Uruguay. That’s a British last name! After reading your post, it makes sense

I’m 56 and used to listening for the pause before others try to pronounce my name. I am happy to volunteer my name before they make the attempt; I think it is polite and gracious to do so. I may have a unique opinion on the pronunciation of my name; each of my parents pronounced it differently. I am named for a great aunt, and my name is Najla. Growing up, my Lebanese father and my Lebanese friends who speak Arabic pronounced it Nuhj’la (like “nudge” without the ‘d’, with a ‘la’ at the end). My mother and most all other family and friends called me Nahj’la, or just Naj (like the Taj in Taj Mahal). I always ask students to say their names. I repeat each name back to them, and then write the name phonetically on my roster. I always ask if the name has a special meaning, and tell them that mine means “beautiful eyes” in Arabic. They visibly relax when their names are pronounced correctly, and they have pride in their voices when they tell others of the special meaning of their names.

What do I do if someone butchers my name? I smile, make eye contact, and politely (and slowly) say “It is Najla – just five letters and two syllables. I know it is different from other names you hear, and you may call me Naj if it is easier for you to remember.” I also don’t take it to heart. I may never see him or her again, and if I do I want to be remembered as being assertive yet gracious.

Thank you for the article.

I’ve been struggling with this whole my life as well.

Recently I made https://sayitlike.me to solve the problem, to some extent.

I understand your point. But mispronounced name is only a small part of the immigrant experience. When I was in school I was not bothered by teachers settling on an altered version of my name. What bothered me most is teachers asking me to share my background with the class. It’s as if they asked me to make sure that my peers never ever forgot I was a foreighner. Let’s not forget that young immigrants may want to assimilate and be part of the group ASAP. So if that means odopting a nickname and moving on so be it. Assuming that a student wants to share his/her background and prying can lead to more isolation. I guess what I’m saying is: now that you got my name right, see me as an individual not as representative of another country.

Thanks for sharing this, Steven. It’s something a lot of well-meaning teachers probably do, thinking they are making the students feel valued, when they don’t realize it may have a more negative impact.

I have built a name pronunciation, NameDrop (https://namedrop.io), service to solve this problem! People (students included) can record their own names and share it alongside their contact info (teachers included – we are already working with London Business School and speaking to other schools).

Beauty is that students are engaged in the process and they can say their name however they like, reinforcing their identity.

Would love to share more with people interested. BTW it’s Free for individuals to sign-up

Hello Jennifer. I listened to your Podcast and reminded me of the following post I wrote in 2014. I called it “Stories Behind the Scenes from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary Commencement 2015”.

“Stories Behind the Scenes from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary Commencement 2015

“In many things and many times, little details escape our recognition. During Commencement (Graduation) events of universities, colleges and seminaries in North America, names of graduating students are called out one by one as they walk up to the rostrum to receive their diplomas and that wonderful handshake from the President and from the Academic Dean of their respective institutions. One little detail that seems to escape our recognition is the work that goes into calling those names. In the United States, for example, universities, colleges and seminaries are microcosms of our global village. Thus you will be sure to find names from China, India, South Korea, Indonesia, Cuba, Barbados, Argentina, Brazil… You will find Igbo names (like Anyanwu, Ekeanyanwu, Iwuanyanwu, Nwogwugwu etc), Yoruba names (like Akinola, Olarinwaju, Aboderin, Akinsoroju etc), Bachama names. You will find in the list of graduating students in the Commencement Programs, names of my brothers from Al Magbrib (Morocco), from Msri (Egypt), from Lubnan (Lebanon). Slovanian, Croatian, Russian, German and many more names are not left out in those lists.

“So during the just concluded Commencement of our Seminary, I was listening with intent to Scott Poblenz, who is our Dean of Enrollment Management and Registrar, calling those names. I wondered how Scott got to pronounce those names. One may not understand the difficulty except you’ve had some brushes with languages. Our first Arabic teacher was not happy that Dolapo and I could not realize the pronunciation of the Arabic sound for خ (close to kh or the German ch). So one day, Dolapo told him to pronounce her name “Dolapo.” He could not realize the sound for “p” in Yoruba. He was rather calling the “p” (which is close to kp in Igbo) as “b”. So instead of Dolapo, he would call “Dolabo”. Imagine yourself being an American and pronouncing this Igbo name: Innocent Alozie Nwogwugwu! Or pronouncing my own last name: Uchenna D. Anyanwu. What of those tongue twisters in Chinese and Korean names? Just imagine it!

“So I found Scott Poblenz, days after our Commencement and I was appreciating him for the pains he took to pronounce correctly as much as he could those hundreds of names. I was amazed by what he told me. Scott, told me he had to put in about 5 hours practicing to pronounce the names to help him get used to them so that he could pronounce them correctly at the Graduation Event. He said: “Peoples’ names are important to them.” So it is important to seek to pronounce them correctly when they are being called to walk up the rostrum to receive their diplomas. I agree with Scott. By 2016, some of the names Scott Poblenz would have to practice ahead of time before the Commencement day will include Olatunde, and Birgen Mathew Kipchumba (from Kenya) and many more. Please pray for Scott! I am very certain that in 2017, whoever will be doing what Scott Poblenz does for Gordon-Conwell at Gordon College, Wenham Massachusetts will have an uphill task. Why? Because then my son, Ezeanyinabia Uchenna Oluwadamilohun – Eze Anyanwu – will be graduating from Gordon. And the person will need to really work hard to pronounce Ezeanyinabia (Our King is coming) well, talk more of Oluwadamilohun (the Lord answered me). “Does all this matter?” you might ask.

“Yes, I think it does. When the roll will be called up yonder, the names of those who have followed the Lord will be called and they will match on to enter into His glory. I am sure whoever will be saddled with the responsibility of calling our names at the Matching-In Ceremony on the other side of eternity, will certainly pronounce the names correctly. It catches my attention that this is one of those little details we often overlook.

“Meanwhile, thank you so much Scott Poblenz (whose last name I still stumble in trying to pronounce it) for all the hours you did put into your work. A special thanks to you, Scott, for pronouncing Anyanwu well at the Commencement. It meant a lot to me. Was it part of the job description when Gordon-Conwell was hiring you for your present position?”

When parents give their children names that are spelled counter to English phonetics, then the teacher has the right to point out to the student that they may be perceived as uneducated if they do not change the spelling of their name. For example, I had a student who spelled his name “Dyane” but said that it was pronounced “Duane.”

You guys sure are delicate little flowers. Get over yourselves! My nameS have been mispronounced as far back as I can remember. I have more important things to worry about.

I grew up in a border town and attended public schools where I was a minority. Many of my teachers were native Spanish speakers. Many of them couldn’t (or wouldn’t) pronounce my name, Laurie, correctly.

My first day of 7th grade in South Texas the teacher mispronounced my first and last name with such a heavy Spanish accent I didn’t recognize it. In fact, my best friend calls me LOUDA to this day and we laugh and laugh.

All my life I’ve accepted just about every mangling of KIOUS imaginable. Kee-us; Kai-oss; Kai-oos; Kees; Koos; you name it. I just laugh and say “Kious” (like Pope Pius with a K). Good thing I didn’t get upset or I’d have ten ulcers by now and be languishing in anxiety like the little lambkins who worry about such things.

I Think I know the feeling!

I had a friend who was Japanese and she had a problem pronouncing my name because of the first letter L. I never thought it was offensive, racist, or a micro-aggression. If I were to attend school in Japan it would never occur to me that the teachers were seeking to belittle me because they had a problem pronouncing my name. Its amazing to me what people find offensive these days. How do you make it through the day?

I’ve had a lifetime (65 years) of explaining that my name is not Valerie, or val-er-ee-ah, and remember as a child envying my classmates who had the typical female names of the times, like Debbie or Sue or Janet or Kathy. I was a timid child, and correcting a teacher or others in position of authority was difficult for me, especially when I had provided the right pronunciation earlier. And yes, my name was mispronounced at all but one graduation/commencement.

It was especially defeating when someone would insist I spelled my name wrong, which happens to this day. My given surname was also usually mispronounced, and that’s why I adopted my spouse’s last name. I simply got tired of explaining my first name and my last name. It’s also part of the reason I gave my children the names they have, Margaret and Robert.

What gets me is how some people act offended when they’re provided the correct pronunciation of a name. While no one would characterize me as being timid now, I have learned to provide a mnemonic to help others pronounce my name correctly. I don’t relish having my name associated with malaria or planaria, it does provide some levity and people tend to remember. And yes, I make an extra effort to pronounce names correctly. I know how it feels.

You say your name is not pronounced “val-er-ee-ah”; this, however, does nothing clarify things as no syllable is accented. I would pronounce your name “val-AIR-ee-uh.” Is this wrong??

I admit that I bristled at the headline posted for this blog. Microaggression is just another word to label negatively anything that does not match the Lefts/academics view of how we should act, think or feel.

I do though after reading the article that the author has their heart in the right place. I do think ideally we all should attempt to get others names correctly. I do think though there are cases where you can’t expect perfection in terms of. pronunciation on a first try or several. I think it’s a faulty assumption to determine that someone does not care about someone else based on an incorrect pronounciation of another’s name. Ideally it would be great if we were so limber with language.

I have a last name you’d think would be easy to remember or announce, but invariably someone can literally read the name “Christen” then in explicitly say “christensen”. There is no I’ll will or aggression attended and I know it.

My partner’s name is Ariel. He’s Spanish. His name is pronounced the Spanish way: ah-ree-EL, emphasis on the last syllable. Not like the Little Mermaid or the antenna on your radio. I think a lot of people are genuinely confused, but it really doesn’t seem that hard to remember.

What’s also amusing is that some people aren’t aware that Ariel is a unisex name. We’ve had people thinking we were a lesbian couple because of that 😛

Oh, and the other one that gets my goat… people who insist that “chorizo” is pronounced “cho-rit-zo”. It’s Spanish, not Italian!!

I highly recommend checking out this video “Facundo the Great.” https://youtu.be/s8FheuSE7w4

I moved from the Midwest to New York City when I was 17, and my simple name was constantly pronounced either “Teddy” or Tuh-ree (Brooklyn version). I got so sick of it I longed for the sound of just plain teh-ree.

I’ve always made an effort to pronounce a person’s name the way they want it pronounced, even before all the multi-culti became a big deal. It does matter, and it’s a small effort that has a big result (i.e., leverage).

The bigger annoyance to me is people who won’t bother to spell my name right. It’s one “r”. I mean, when my name is spelled with one “r” in my email, and I sign it, “Regards, Teri” and they send it back starting “Dear Terri.”

I used to work with a woman name Genevieve, and was careful to always spell it correctly, because I do that for everyone. She would go ballistic about people misspelling her name, then send me emails addressing me as Terri. I considered butchering her name back, but she was so self-absorbed she wouldn’t have caught the point.

I found this year (my first year teaching) that aside from pronouncing names correctly, some of the students were amazed that I would spell their names correctly on passes – capitalization, punctuation and just plain spelling. Jae’Veon was a little less obstreperous, JoJuan was frankly amazed, and so on. I’m a very text-oriented person so I wasn’t even doing it consciously, it’s just that once I’ve seen it on the roster a few days in a row there isn’t any other way to spell it.

Ending rant: I prefer to be Mrs., because I am. The students call me Mrs. but my administration doesn’t. The vice-principal and the librarian and the over-achieving social studies teacher are Mrs., but I’m Ms, most of the time, regardless of always signing Mrs. (and we’re all supposed to call each other Mr/Mrs/Ms LastName, to model for the students). By the end of the year a lot of people were calling me Mrs., but then at graduation it was back to Ms. I don’t even know who to talk to or how else to communicate it.

Why do I care? (A) I’ve been married for 35 years. (B) I teach Family Studies, so I’d like to make clear that I value marriage. (C) I’ve earned it.

Ok, that’s enough!

On the first day of school, I write on the board “My name is _______. I go by _______.” While the kids are working on something independently, I’m stalking around the room with my clipboard and roster, so the kids can read those two sentences aloud and fill in the blanks. ALL of the kids introduce themselves to me this way. I make pronunciation notes and reminders about “goes by middle name,” or “uses Bobby instead of Robert.” I hear the preferred name before I ever attempt it myself.

I’ve had kids say “You’re the only teacher who says it right.” That’s sad, because getting a name right isn’t that hard.

I have always tried to be very sensitive to this in my classroom. I teach in a culturally rich area, and from Day 1, I create pronunciatons on my attendance sheet. I also check privately with students until I am sure that I am pronouncing the name correctly. Prior to Awards Night, our administrators double check with teachers to make sure they are pronouncing names correctly.

I teach ESOL, and they’re by no means all speakers of Spanish, French, and Mandarin (languages which I know how to pronounce). I have found that many appreciate this kind of opening gambit:

Excuse me, but I am not sure I will be able to pronounce your name correctly. But I would appreciate your help in getting it right.

As a retired teacher/substitute in academic Magnet schools in Philadelphia, there are lots of immigrants and lots of ‘different’ names. I start by announcing that I apologize in advance for mispronouncing the name and please don’t laugh at me, it makes me feel bad.

I’m always impressed by the cultural differences between how the students react to mispronunciations. Some respect the teacher and don’t correct me. I’m very put off by the students who correct me with an attitude that suggests I am rude to them. Belligerent.

I’m glad you address it. Your explanations are more individual than stereotypical. I do think there’s a cultural component.

To the belligerent students, I mention that I gave my daughter a hard to pronounce name. I had to teach her at the age of 5 to be respectful and not keep shouting at the person until they got it right.

I do ask, and try to show respect to get their names right.

I’ll never forget my African American professor not even attempting to pronounce my or my friend Rhea Lana’s names in our College Algebra class. I didn’t feel discriminated against, but I did feel that he could’ve given it a little more effort!

It is difficult, though, when names contain sounds that English speakers are unfamiliar with. My boyfriend’s name contains a hebrew “ch”- similar to german “ch”- and people typically just replace it with a “k” because they don’t know how to make (or even hear) that sound.

On a more broad note, I teach at a university, and have many, many Chinese students, and it took me a while to realize that the reason I couldn’t get their names right was that I was misproducing the *tones*. I can’t even hear the tones, and I’m not at all confident that I could learn to produce them correctly without learning Chinese…

Ok…. so i call the roll of like 300 students a semester who i see twice a week for 15 weeks…..when i come across names i cant pronounce (which happens)….which is more of a microaggression if i am corrected….to say ok and never really pronounce it right or stop class and make him pronounce it as many times (like 5 or 7) until i say it like a native khmer would say it….and then realistically due to muscle memory in my vocal cords still not say it right if i call on him in 2 weeks and having to memorize the names of 300 other students in said lecture hall…i see what youre sayin but is it realistic

Serious question since monday is fidst day of class

This is a valuable article, and a good one to think about as the semester begins. I have many students with unusual-to-me names and I try very hard to get the pronunciation right. I will try even harder. But I also want to note that I’m hearing impaired which comes with speech issues. I sometimes cannot hear or produce the pronunciation correctly, which is frustrating. For example, I cannot hear any S or Z sounds. I have learned to make them, but I am sure this keeps me from saying some names as they ought to be said. As far as I can tell, my students have been understanding about this, and I am grateful for it. It’s important to remember that teachers are fully human too — with disabilities and “unusual” names and backgrounds, too.

Dear Shannon, you are pointing to a fact that I have seen missing a lot. I understand and share the point made about micro aggression. We should also emphasize politeness on the side of the person caring the name. Because correcting somebody mispronouncing your name can also be micro aggression.

We should also be talking about human speach limitations. Of course children will pick up the correct pronunciation of their classmate names. They are still in a fluid state of their language development. But as you get older, sounds become hard-wired in your brain, and not just in the pronunciation, but in the hearing. We can try it best, and that’s the best we can promise… Your mother tong impose a limitation to what sounds you can reproduce. And saying that words are just syllables put together is true, the issue is that normal people, after living more than 10 years, can’t hear or reproduce all the different syllables of all the languages in the world.

I’ve been lucky to have an easy to pronounce name (where I’ve lived)

As a teacher I always start taking attendance by apologizing for mistakes I’m about to make, and asking the group for help.

I tell them that only the _owner_ of the name is allowed to make corrections or help with pronunciation. (Teaching teenagers for th most part)

First, when three kids call out a correction , I end up confused about who “owns” the name. Second, moving to a school with less diversity than past jobs, I discovered that i was one of only two people who was saying a particular name (mostly) correctly. The other students were shouting out the wrong pronunciation, which this boy was used to putting up with.

I come from a small town and one of my friends in my year had a name that is uncommon in our area. Whenever substitutes came in and made a pause during roll call, the whole class would chorus “It’s _____!!!”

Story of my (school) life. =)

Some names are just really hard to pronounce and remember. So, I basically spend a lot of my time planning worthwhile lessons so that my children will be able to get a job and support themselves at some point in their lives. I let them know that this will happen throughout their lives and not be view this as bigotry in any way. The moment you allow your students to not view themselves as victims, the happier and more successful they will become.

My first day of 4th grade at a new school in a room filled mostly with strangers had an inauspicious start.

The teacher in her infinite wisdom gave the class roll to one of her favorites to take attendance.

My last name begins with an “S” so I had the anxiety of waiting and waiting for my name to be called.

Finally when my name was called it was totally butchered and the cause of laughter.

So 54 years later it remains a vivid and unpleasant memory.

What complicates this issue on an introspective level is when you move to a country where the official language uses a different alphabet. In that case, your name becomes a transliteration (and one created by strangers, at that) and may never feel like “your” name. That has been my experience. I never felt too strong of a connection to my last name because I knew it was impossible for it to be pronounced the way a native speaker of my language would say it – the letters and phonetics were different.

By the end of high school, when I had just started to own my last name and feel like it was part of my identity, my parents decided, without much discussion, to shorten it and make it easier to pronounce. Ironically, people still trip up and I have to go through the agonizing five minute discussion of how to say it (always ending with a validation of their still-incorrect pronunciation). So it’s the same story, but now with a last name that is even farther from the original than the previous one was.

And I don’t fault the people who can’t pronounce it right. I understand it’s hard for them. But I also don’t appreciate having this conversation in the middle of a discussion of a work-related topic, for example. It shifts the attention away from my work and to something about me.

This is great; thanks!

One question though – how would you approach a mispronunciation when it’s not a lack of understanding of how the name is pronounced, but rather an inability to make the sound with your mouth? (due either to a physical disability or to simply having never used that vocalization in a language that you speak)

Thanks!

Hi Tawny, I’m a Customer Experience Manager with Cult of Pedagogy. I was a former teacher who taught in an ESOL school. Kids understand teachers don’t speak their native language…they just want to be respected and know they matter, which includes pronouncing their name. When I was in the classroom, I would meet with my students 1:1 and ask them how to say their name. Sometimes I needed to ask them to say their name slowly, in parts, so I could get it right. This meant the world to them. And yes, sometimes I’d need to be upfront, letting them know that rolling my tongue just wasn’t my strength (and we’d laugh), but that I’d be sure to keep working on it — and that was ok. The effort, respect, and making this important is what matters. Hope this helps!

Pronouncing someone’s name is very important whether it’s their first, middle or last name because it’s a part of they are. It’s also important if one can’t pronounce the name to ask the student how to and learn it because its a respectful thing to do and it also shows the student that you care about them.

I always make an effort to have the students’s names with faces & correct spelling/pronunciation within the first few days. As a mother of twins, I always try especially hard in this area. It’s way too easy to group twins as one unit.

I’m so happy to have read this article because it confirms something that hasn’t been sitting right with me. This school year, my colleague Kate and I decided we would not again contribute to the (surely anticipated and repeated) mispronunciation of any student’s name. A name is a symbol of identity.

So instead of starting class with the classic calling of roll and assigning of seats, we left instructions for each of our students with names on them on the desks. Students found their names and got to work, and meanwhile, we were able to go from student to student, asking them what their name was and what they liked to be called. The first people to say each of their names were the children themselves, and it was never mispronounced aloud to the class. At that point, I would make a note of their name phonetically, introduce myself, and shake their hand (because I’m old school and dorky like that). We did this no matter how common or unique a student’s name was.

It was my favorite first day of school yet, and I believe it set the right tone.

Lauren, thank you so much for sharing this; I’m sure other teachers will want to use this same approach!

This was an interesting podcast until it became very racist between 13:55 – 14:35. She said that because Ryan Seacrest couldn’t pronounce the actors name (Quvenzhané) that he is sending a message that a little black girl’s name is not worth learning. What BS, she even compares it to the fact that everyone learned Arnold Schwarzenegger and Renee Zellwegar’s names even though they too are hard to say. So funny, Renee’s name has been in the spot light for over 30 years. Arnold was “Mr Universe” at age 20 in 1967, he has been in the spot light for 51 years. So yes their names are known by the world. I’m sure if Quvenzhané is in show biz that long, her name too will be known by the world. I think this was a very tasteless inclusion that a good point.

My student teaching experience took place at a school with high Hispanic and Ukrainian populations, as well as several transgender students, which led me to the idea that it might be better and more respectful to ask the students what they prefer/how to pronounce. On the first day of class, you could ask students to introduce themselves (first and last name) and then repeat their names to ensure you pronounced them correctly. This could be where the “writing them down” thing comes in. Sure, you might have a few students who take this as a joke and give you a fake (inappropriate) name, but I think most would see it as a respectful effort and if introduced correctly, would lead to a stronger classroom community.

I have a name that is easily to pronounce, but everybody pronounce it differently. And also puts accent differently. As it is common in English language they pronounce as they used to, but to be truthful, it is not how my mother family are calling me since I was born. So when you have universal name, it is hard to correct people. I don’t mind it really how they call me, but I do mind they don’t even ask me is that correct. They just assume all world say it the same, and I refuse to believe they are ignorant to don’t know it is not the true. For surnames I understand and don’t expect they will remember even if they try, I know it is hard. But it is great feeling when someone makes an effort.

My family name is long and difficult to pronounce. I had a teacher in high school who could never be bothered to pronounce it right even though she was Russian as well. When I moved to Europe, I relaxed and let people mispronounce it simply because it’s a foreign family nsne, and I appreciated their hard tries to pronounce it correctly. So most of the time I would just offer them to address me using my first name. For the graduation ceremony the announcer practiced a lot, of course, so all tricky family names including mine were pronounced correctly, and I felt happy 🙂

However, as a teacher, I always try my best to pronounce my students’ names the right way. If I see some name I don’t know how to pronounce (usually it’s a Vietnamese or Chinese name), I ask the student to model it for me and then I write down a transcription.

I once had a teacher named Mr. Wasil. He didn’t want to bother learning how pronounce my unusual name, so in front of an entire class of teens, he asked , “Can I just call your Lisa?” I said, “Sure, if I can call you Mr. Weasil.” Everyone cracked up, and he learned my name very quickly after that.

My oldest son’s name is Eetai. He LOVES his 2 “ee”s at the front, and refuses to simply be called “Ty” to help people out. He told me, “Mom, I’m not giving up my cool front letters just because people get creative with what they call me.”

Names are who we are. It’s so awesome when teachers bother to take the time to get them right when they’re hard to learn. It models respect in such a beautiful way and says, “I see you.”

I love everything about this! Thanks for sharing!!!

I grew up in a very small community with a very common maiden name, however, at my comparatively enormous university graduation, they had each of us write our names out with the pronunciation spelling rather than the actual spelling. As a result, my hyphenated married named was pronounced perfectly by a professor I had never met. No easy feat when my husband’s last name’s pronunciation depends on the language of the bearer.

Thank you so much for this post! I come back and read it often. As an immigrant teaching in NC, I found that students have much less of a problem pronouncing my name than coworkers.

I was wondering whether you know of any texts about the correct pronunciation of names that would be accessible to (middle-grade) students? I am writing a unit about names and want to make this issue present and acknowledged.

Thanks!

I use Flipgrid for this – students make a short video introducing themselves, and I get a record of their preferred name and exactly how to pronounce it. Thanks for this great article on the importance of naming, I plan to share it with other teachers.

Erin this is an awesome tool that I had not thought of. It is then there as a record for future reference.

As schools become more and more multicultural, a school I work at has a large Chinese boarding population, it is very important to show respect by starting with something simple like getting their name correct.

My name is rarely mispronounced (though when I started teaching in Latin America, I got called “Miss B” instead of “Miss V” on a regular basis), but my first name would get misspelled all the time. I remember teachers adding an H to my name even when they were copying directly off of an attendance list. It made me feel like they were too lazy to care about my name. Now whenever I have students whose names could have multiple spellings (or it’s not a name I’m used to), I always double-check with them.

Jennifer, I have a unique last name – so I really appreciated this article — I listened to the podcast too. I have made an effort to ask others to help me get their name ‘right’ as I have always been excited when people have taken time to get mine ‘right’ too 🙂

I was surprised to hear and see your suggested pronunciation of Dougherty. I had never heard this name pronounced with a “Dock” before and this seems to be an an anglicized pronunciation, which is what I thought you were trying to avoid. I had a French teacher named Dougherty and we said DOH-er-ty. https://www.irishpost.com/life-style/13-irish-surnames-that-are-always-mispronounced-in-britain-122218

Sometimes, anglicized pronunciations become the norm. The French pronunciation of Braille rhymes with “rye” and the French pronunciation of Cadillac pronounces the double LL as a Y.

Excellent information in this blog. I’ve been teaching for only two years and am certain that I’ve messed up my students names more than once. Most of my students are from a rural Hispanic area and I often find their names very difficult to pronounce. Knowing now what I learned in this broadcast I’ll make every effort to speak their names correctly every time. Thank you for highlighting the significance of this topic.